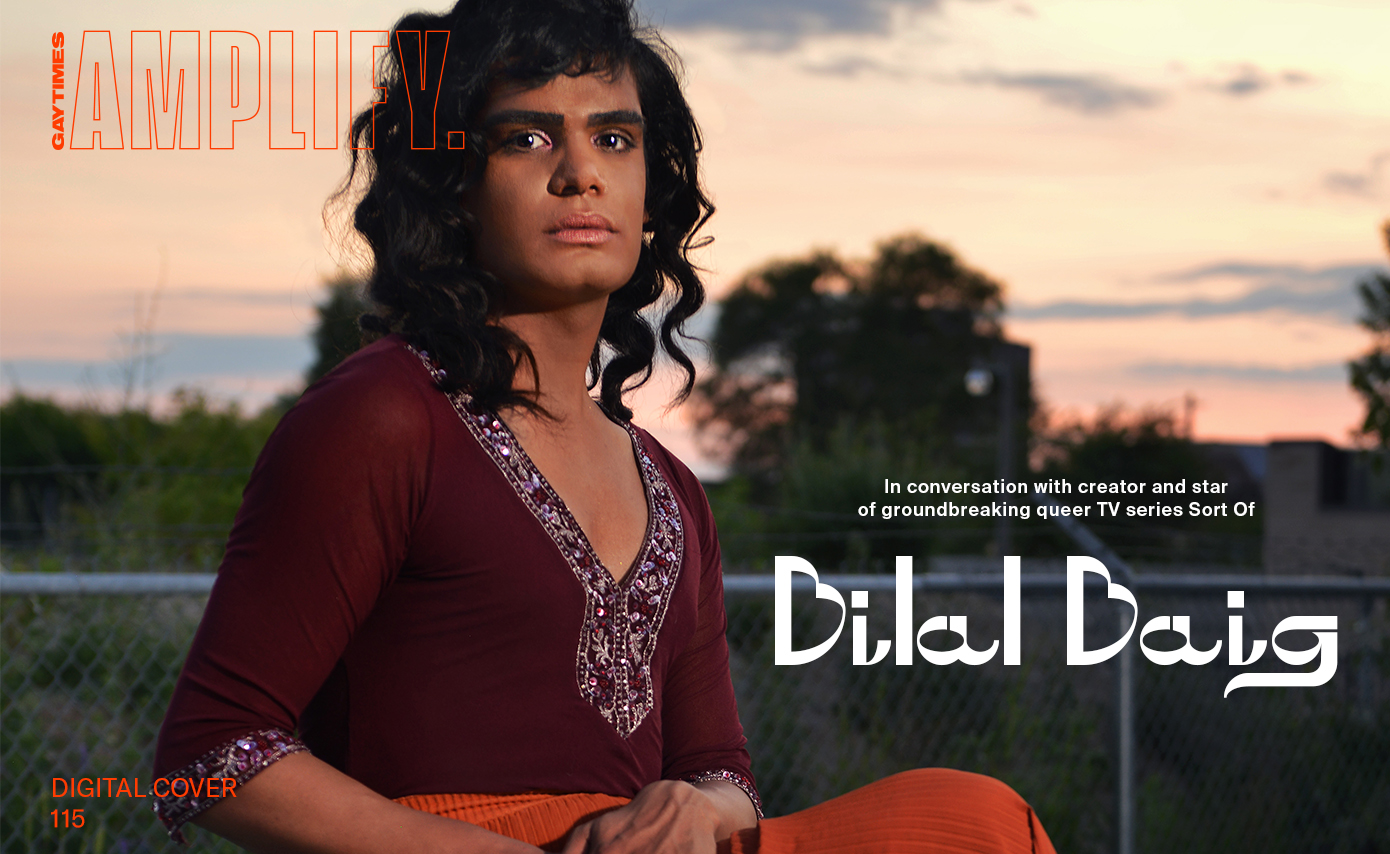

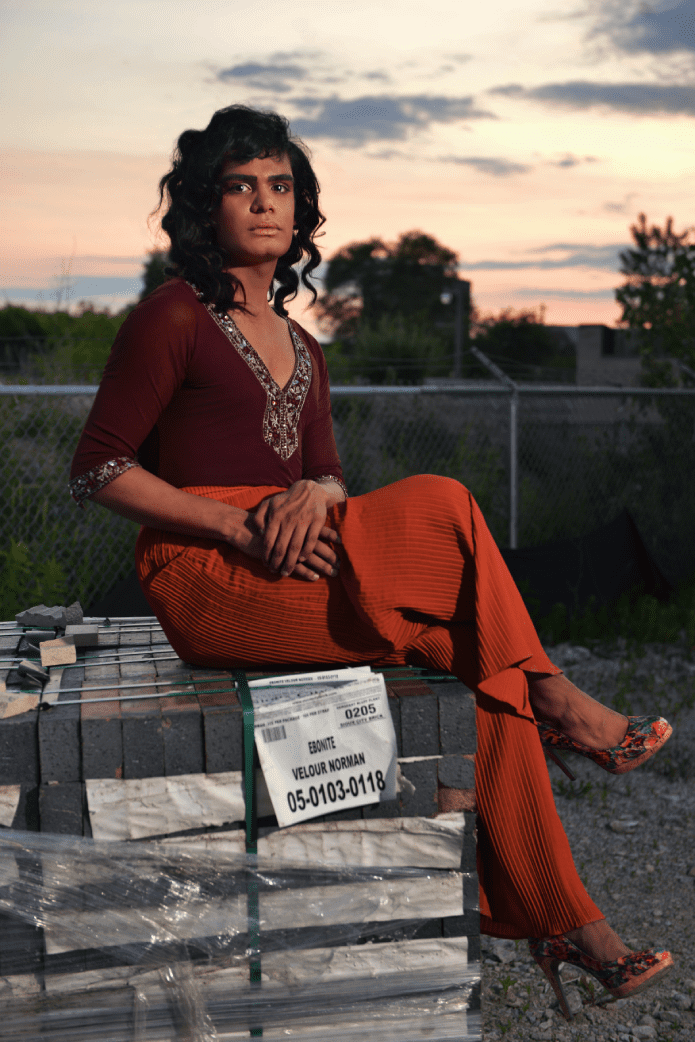

“I’m not married, I don’t have kids, and, of course, I bring the trans and Brown mom stuff together, and that is essentially what makes Sort Of,” Bilal Baig quips over a Zoom call. For those who have watched Sort Of, Baig’s deadpan humour is a shining element in the original Canadian series. A nuanced comedy-drama, Sort Of digs deep into questions of identity, death, and callings of the heart, with lead character Sabi Mehboob at the centre of it all. Baig, the creator and lead star of the series, steps into the shoes of a twenty-something Pakistani nanny who characteristically embarks on an enthralling adventure of self-discovery. Most notably, Baig and co-creator Fab Filippo steer away from dressing up their characters as flat on-screen stereotypes but, instead, offer earnest visions of humanity and empathy.

Leaning on their own experiences and creative experimentation, Baig and Filippo ended up “swapping life stories back and forth” before cultivating the backbone of this thoughtfully complex series. Sort Of soars as a proven example that intersectional representation and solid storytelling deserves a home on our screens. Sort Of candidly whips through heavy topics with a zany brand of comedy that succinctly ties to the understandings of queer and Brown communities. “It’s really fulfilling for me to know that it’s reaching people because we work so hard on something and then you sometimes just don’t actually know how specifically it’s resonating for certain people,” Baig reflects on GAY TIMES’ endorsement of the show. “I love when I’m talking to Brown people about this show and queer and trans people. There’s just a way that we just sink into conversations a little bit more deeply, so I really appreciate this conversation.”

Following its breakout success, Sort Of has been renewed for a second season. We caught up with Baig to hear more on the inner workings of the hit CBC and HBO Max original show, their thoughts on the universality of transitioning, and why sincere LGBTQ+ visibility is much needed in the media.

Sort Of relies on an autobiographical element as your own experiences are interwoven with Sabi, the main character. How did you navigate your personal boundaries when creating and writing the show?

I think that’s a great question. The show came at the right time in my life as an artist. Prior to Sort Of, I had worked on a play that I wrote that had its world premiere production in Toronto in 2018. I spent five years working on that play and it was integral in helping me understand how much I want to reveal myself to the world. It’s a fine line, but I fell in love with this idea that happens to intersectional artists, but we get branded as autobiographical and that we have no creativity of our own. We must be pulling from our rich and traumatised lives and that’s what makes our art. At first, I was so upset at why we’re seen this way and that this isn’t the same thing we place on other artists, but then I was just like, why don’t I lean in and actually make money off this shit!

I do bring in some personal truths and points of view I have into the show, but there is a lot of fiction too. I think that’s really important because it ends up coming down to mental health and making sure that you’re doing something that feeds you artistically but doesn’t exploit you in any way. If I didn’t have that experience working on the previous play that I wrote, I don’t think I’d be able to come to Sort Of and be clear about which parts of myself belong to Sabi and where it’s totally separate.

In the pilot episode, Sabi talks about taking their first queer steps. Can you share some of your first queer pop culture steps or experiences?

Bollywood films that I was consuming as a kid felt very queer to me. Even though they were hetero characters-slash-actors and always male or female, there was something so queer about the flamboyancy of the dance sequences, the costumes, and the attitude. It’s so over the top, it’s almost campy. I remember seeing gorgeous Brown men and women in films, which really helped me to identify what I prefer romantically. It definitely became the basis of so many of my dreams about ‘Oh what could it mean to tell stories and through which kinds of bodies and colours and songs.’ For so long, all my family did was watch Bollywood films, even though I grew up in Canada. And then when I got to high school, it suddenly mattered what I was consuming, and then queerness really came through. We referenced Archie Punjabi’s Kalinda on The Good Wife in Sort Of with the boots. Kalinda was a pretty big deal for me, in what that character represented.

On a smaller scale, the Toronto theatre world also started to really define queerness in art for me. Getting to work with queer and trans artists and I thought that was really compelling. I may have come into this world assuming more things were queer rather than they were straight. I tend to see queerness in everything almost, versus thinking, ‘Oh, this world’s not made for me, how do I exist in it?’ I lived in my head a lot as a kid too. I was quite quiet, and dreaming a lot, so I think I made everything queer because I thought it was cooler that way.

Critics and reviewers of Sort Of have focused on the elements of representation within the show. As the first South Asian, queer, Muslim actor to star in a Canadian prime-time TV series, how did you ensure Sort Of delivered authentic storytelling that didn’t feel tokenistic or disingenuous?

There’s a couple of things. We knew from the start that we were going to have Brown and queer writers in the room and that we were going to work with trans consultants; we knew we were going to prioritise hiring Brown women as the second director on the show, because Fab directed six out of eight. There were things in place that we collectively agreed on as a core team and that made the difference. If I was working with producers that wanted to do the tokenist-y thing, I’d have a really hard time working in that space and maybe, seriously, consider wanting to quit creating TV. But, for my first experience in all of this, to have the team that I did, was next level. There was a lot of kindness and a constant space for me to express what I want something to feel when we’re creating certain characters.

Authenticity comes from artists forcing themselves to be the most honest versions of themselves and their characters

I think authenticity comes from artists forcing themselves to be the most honest versions of themselves and their characters. I really value that and think there’s beauty in it. It doesn’t mean that the product comes out super clean, cutesy and nice, there’s still an edge there. There’s darkness, there’s pain and joy. I’m so tapped into my communities, everyone I know is Brown and trans in my life, and so there were a lot of conversations questioning: ‘What are we missing? What can we do next? And why aren’t these shows that include trans non-binary characters still not enough for us?’ So, it’s all of those things coming together and informing the creation process, but it’s fundamental in having a team that genuinely cares about doing this right and doing it honestly.

As a show that champions diversity and representation, at any point were you concerned being viewed as a show that ticks the boxes?

This is all very new to me and I was aware of rhetoric coming out and perhaps painting this show as propaganda for turning all children genderqueer or something. What I kept going back to was that it will really matter for people who have been waiting for work like this. In hindsight, of course, I don’t know what goes on for everyone who sees a show like Sort Of, but I had a feeling that some of the turnoffs would be: ‘Oh, is this just gonna be a bunch of queer trans BIPOC, woke people?’ I didn’t realise that that could be something that would deter people, versus a response of ‘Oh, I haven’t quite seen characters like this on TV, why don’t I lean in and just give it a chance.’ Thankfully for my naiveness, I didn’t let that thought totally pervade my head. But, I think it’s real and there are people who will think ‘I won’t watch this because it feels too checkbox-y’. But, again, at our core, we are interested in human beings and seeing what these [characters] would do over eight episodes. I wonder about our world and TV-consuming people. What does it take to encourage people to take chances on new things that they wouldn’t necessarily watch or would write off in a certain way?

What does it take to encourage people to take chances on new things that they wouldn’t necessarily watch or would write off in a certain way?

What are your hopes for shows that spotlight LGBTQ+ and South Asian narratives in the future?

I think we’re in the moment and it wouldn’t hurt anybody to just keep going further and trying things. Honestly, at this point it really just feels like, let’s try and fail or try and succeed. I often think to have the amount of space that’s been given to straight folks, cis people, white folks to slip up and continue, this might be premature, but we’re just entering that space now for BIPOC artists and queer and trans artists being afforded the chance to try something. I want to see people, artists, creators, follow the thing that’s turning them on the most, try it, be given funding to try it, to make it, to do it again, and to learn from it. Isn’t that it? Wouldn’t the landscape then really feel like something quite alive? We would actually feel like people that have the space to safely take risks and be super truthful and see what happens, versus pandering to the system over and over again.

We are seeing greater trans representation on-screen and in pop culture. How do you hope these portrayals will shape the conversation around trans visibility and access into media?

When we don’t have faces attached to identities, it’s so easy to harm us because we don’t actually take up space in your mind and heart. We’re just a theory, we’re numbers or stats and we’re not full people with thinking minds and beating hearts. The amount of cis and straight folks who have reached out to me, people in their 70s, who have expressed understanding, confiding that they would ‘shut down’ topics because they wouldn’t how to engage with somebody who’s trans or non-binary. We need to move away from our bodies (trans and trans feminine bodies, non-binary bodies) being harmed, killed and assaulted. It wouldn’t hurt to look at the other parts of our livelihoods and, ultimately, get to whatever story a trans non-binary person wants to tell.

When we don’t have faces attached to identities, it’s so easy to harm us because we don’t actually take up space in your mind and heart.

I don’t think that our show would have existed in the way that it does if it weren’t for shows like Orange Is the New Black leading up to us. I really hope this moment lets our characters flourish and be the full humans that they are. I know so many people have talked about the way Sabi is with the kids and that’s what made audiences feel like they could be relaxed around that character. It’s all about creating empathy.

Last of all, what do you hope audiences take away from Sort Of?

There’s something magical when all of us, including straight and cis people, investigate our own relationship to transition. It’s important to let that word float around and let its definition change as you change. Transition does not only mean changing your body from one thing to something else, it means are you different from who you were five minutes ago or yesterday? Most times, the answer is yes. We are constantly shifting and evolving inside, and externally too.

It would be my dream if we all really embrace what that word means in our lives and reflect on it. Transition is happening all around us. I want more people just talking about using that word. Sometimes it feels like the word has a stigma attached to it, but it’s just a word and we can use it in so many different ways. Ultimately, I want people to use the word ‘transition’ more frequently, comfortably in their conversations, but to really reflect on what that word means, how it applies to them, and the beauty that can come when we embrace change.