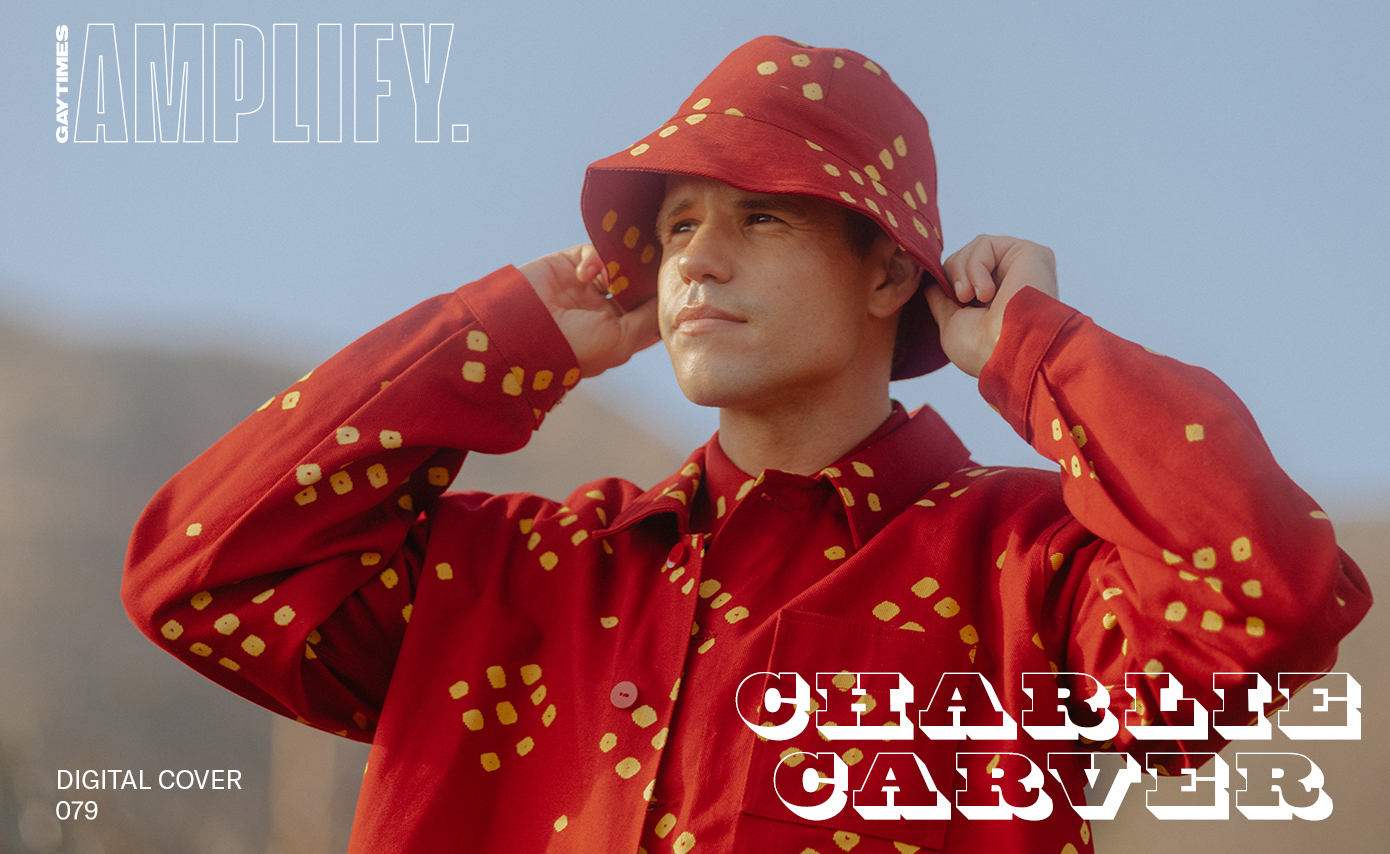

“A challenge is what you want as an actor,” says Charlie Carver. The star, who rose to fame with beloved roles on Desperate Housewives and Teen Wolf, is speaking with GAY TIMES about his two back-to-back Netflix releases from Ryan Murphy, the undisputed overlord of queer media. Set in 1947, the first is Ratched, a drama/thriller prequel series starring Sarah Paulson as the infamous nurse from One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, with Charlie portraying Huck Finnigan, a disfigured war veteran and orderly with whom she builds an alliance. Upon release, it topped the Netflix charts in over 50 countries.

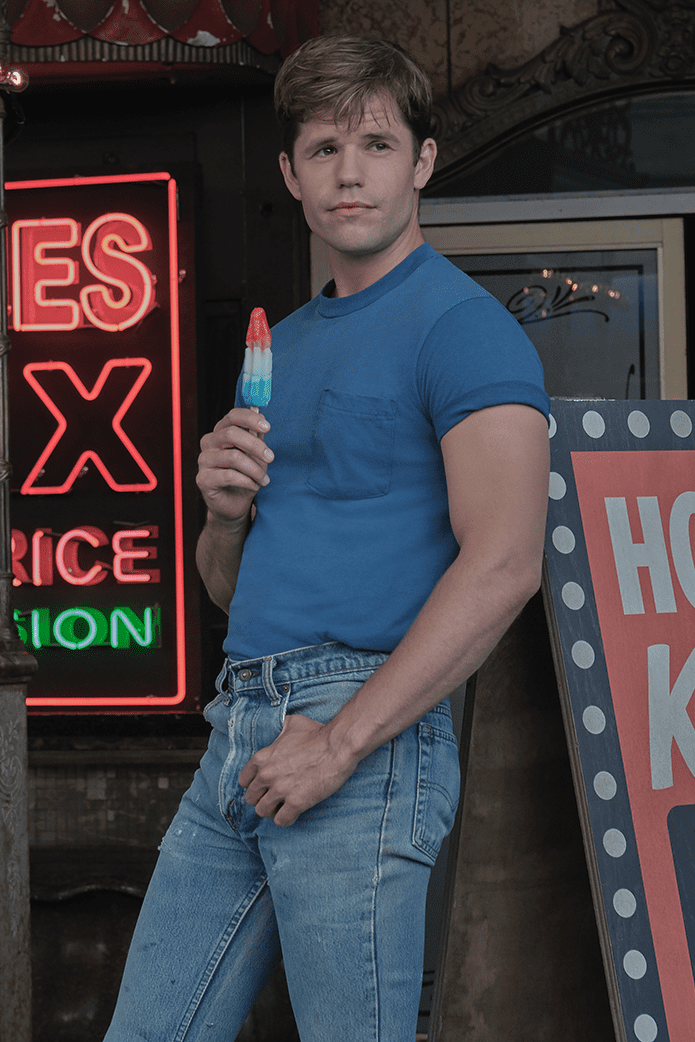

The second is another film adaptation of the widely-acclaimed 1968 play, The Boys in the Band, which sees the actor reprise his role from the 2018 Broadway revival as Cowboy, an easy-going gay hustler. The stories of Huck and Cowboy couldn’t be more different. Despite this, both characters are the shining light of each respective project, and arguably, ahead of their time. Huck is loyal, kind-hearted and one of few characters from Ratched who isn’t prejudiced towards the LGBTQ+ community, while Cowboy is the only gay man in The Boys in the Band who isn’t struggling with shame, self-hatred and internalised homophobia.

“I think he is somebody who just wants the truth to be spoken and shared,” Charlie explains of Huck, later adding of Cowboy: “There’s a straightforwardness and warmth to Cowboy, where he’s just going to say exactly what is on his mind. I guess you could say he’s dumb, and that’s easy to make fun of, but he’s almost invincible because of it.” We managed to catch up with Charlie over Zoom in between filming The Batman (!), in which he stars alongside his twin brother Max, to discuss all things Ratched, The Boys in the Band and being part of the Ryan Murphy universe.

What drew you to the role of Huck?

Having all these incredible women at the centre of Ratched, and feeling like I got to be part of that change and storytelling, was exciting. Huck, I’ve never played somebody who had any kind of physical disfigurement as Huck, and Ryan gave me enough time to prepare and do my research; just sort of get into that skin, if you will. That was new for me, and challenging! But a challenge is what you want.

Huck is also a war veteran. How did you prepare to embody that kind of character?

I read a lot and spent a lot of time daydreaming with the information I extracted from research. What’s so interesting to me about that period, in the history of veterans’ rights and the history of the war, is the attitude towards what was different, particularly WW1 and WW2. I think there was such a different expectation of war as this initiation into manhood, but also this kind of grand adventure. There was an innocence to it. The people that suffered the most coming back from this experience, other than the trauma of being exposed to so much violence, were wounded veterans. They came back and were not supported by society at large, being symbolic of that sort of failure in masculinity in some way. I read a lot about this hospital here in London that pioneered a lot of the techniques for amputees and people who needed facial reconstruction or skin grafting, and it’s heartbreaking – but so sweet – to hear about the communities that formed after WW2 that were largely left out of the narrative. The consistent theme throughout all of that seems to be these young men who wanted a sense of story in their lives, and came back and felt like they had lost everything. This tenderness and sweetness, and the way they treated all of the nurses who treated them with dignity when they felt like they couldn’t be seen in the world, I just found it very moving and that’s where the purity of the character came from.

He is the arguably purest character in the series, and we see that when he bonds with Mildred. He doesn’t witness the horrifying acts committed by Mildred, so, how do you think he perceives her?

One of the beautiful details in the costuming that Lou Eyrich, the designer, did was she put an army nurse’s pin on Nurse Ratched’s uniform. That to me, was just this sign that there was this immediate neutral identification between Huck and Nurse Ratched as veterans, as people who understood the trauma of war. Therefore, Huck doesn’t have to hide anything about who he is. His wounds also sort of externalise a lot of the violence that she is so desperately trying to hide or suppress. So, there’s this sort of yin and yang between them – an unspoken understanding. I think because of that, and feeling so seen, Huck trusts Mildred more than anyone and comes to fall in love with her. I think he does believe that her ability to kind of hold space for his experience or his essence is a sign that she is ultimately a good person.

Huck is quite ahead of his time, because he’s one of the only characters who is accepting of the LGBTQ+ community. Why do you think that is?

Huck is somebody who feels like they have lost everything, that they will never be treated with dignity because of how they look. I think Huck therefore has a lot of empathy for what Mildred reveals to him. There’s this sense of relief that he’s not being rejected, despite his advances, because of being unattractive or whatever reason he’s telling himself in his head. So, when Mildred shares that vulnerability with him, it’s the truth. I think Huck is somebody who just wants the truth to be spoken and shared.

The series includes some uncomfortable scenes surrounding gay ‘conversion therapy’ in the 1940s. 80 years later, and the practice is still legal in numerous countries around the world. What kind of message is the show trying to convey with this storyline?

Well I think it exaggerates but very much tells the story of the brutality of conversion therapy. So often we think… You know, I’ve heard stories of actual violence happening in these conversion therapy settings, but even the mental violence and the shaming, the confusion and all of these tactics that are employed upon young queer people to try and get them to change who they are is a form of violence. This show takes that and makes it visceral. So, I think it is a pretty effective way to convey that ‘conversion therapy’ is wrong but even in the new trailer that dropped the other day this notion of humanity being able to play God just because it has the consent of a medical body, I think the show really tries to probe at that.

That twist with Huck at the end… For me personally, it was the most shocking moment on Ratched. How did you react when you read the script?

[Laughs] I know! I knew before I signed up for the job, that that was a part of it, which is kind of an exciting thing as an actor because you know on some level symbolically that the character has fulfilled their part. They’ve achieved something. So pulling that and working backwards in a way and trying to create the biggest arc for the character, by the time Huck passes away – can I even say that? – I felt like he’d finally found a sense of strength and compassion and love for himself. Mildred gave him that when she insisted that he become head nurse. He died in the line of duty and that’s exactly how he would’ve wanted to go. But it is sad, especially when you really start to feel like… Some of those last scenes that I had with Sarah, they’re just so fun to act and were so beautifully written, and to think that the relationship you had with the character is suddenly done, it’s sad. It’s hard. But the funny thing was, I think the very next or the day after, I started principal photography on The Boys In The Band!

You didn’t even have time to mourn!

[Laughs] Yeah. That was a solid, for sure!

You’ve collaborated with Ryan Murphy several times, and so has Sarah Paulson, but this was your first time on a project together – what was it like working with her?

Yes. The first time I collaborated with Ryan was on the Broadway production of The Boys In The Band actually, and I’d known Sarah. Sarah’s good friends with a lot of those boys and I’d spent time with Sarah in New York, but we had never worked together. It is that thing of… I love Sarah, she just lights the room and she’s so fun, but suddenly you’re acting across from Sarah Paulson as opposed to the Sarah that you spend time with! I was pinching myself. I was pinching myself quite often through filming the show and just going, ‘Oh my god, this is Sarah Paulson. I better show up.’

Let’s move onto The Boys in the Band. How did you find that experience, moving from theatre to TV with this incredible ensemble cast?

It was such a gift to have the entire Broadway cast and the Broadway creative team, and then having a lot of the film crew from Ratched and the creative crew moving over to do The Boys In The Band as well, as a part of the Ryan Murphy world. I will never have another experience like that and as Jim Parsons said very recently in an interview, I can’t imagine doing anything differently from now on. We all knew the words [laughs]. We knew the story, but that’s not always the case when you show up to a set. To have that sense of trust amongst the cast and crew and with the director, and having a large part of everybody there be out and proud, it was just so fun. It was so fun and because it’s all shot in pretty much one location, we shot it in chronological order, which also rarely happens on a set. Every day was just… We knew what we’d done and we knew where we were heading and had nice little lunch breaks and great catering and it was a real gay old time. It was great.

Did you face any obstacles with the new format?

Well I think at the beginning it’s a question of how do you modulate a performance that you’ve done so many times in the theatre and keep it fresh and bring it down more, into a filmic reality? The biggest challenge for me was that in the Broadway production, you’re so used to having the audience and the laughs give you a sense of rhythm. A lot of the jokes are very traditional like, ‘Blah blah blah, one, two,’ whatever. It’s almost like a sitcom, right? But on a film set, there aren’t any laughs, so how do you tell the truth and not ham it up and kind of bring it into a more natural place? So, the first day was just a little nerve-wracking because you’re trying to figure out what that’s going to feel like, then from that point on we all kind of had found our respective new space and ran with it.

Like Huck, Cowboy is pure and kind-hearted. However, he’s constantly mistreated and undermined by the other characters. You’ve played him since 2018 – why do you think the boys treat him like the butt of some joke?

I think they’re envious of his youth and maybe his looks, the sort of kindness with which he responds to everything. There’s a straightforwardness too, and warmth to Cowboy, where he’s just going to say exactly what is on his mind and he perceives something as literal as possible. I guess you could say he’s dumb, and that’s easy to make fun of, but he’s almost invincible because of it. The other characters are trying to get something to land on him and they can’t quite ever do it [laughs].

They say some pretty awful stuff to him, and he does not flinch. I love him?

[Laughs] He’s just a puppy! He’s just excited to be around these cool, wealthy Manhattan gay guys. It’s not where he’s from. I love him too! It was another opportunity to do some research, just because I’m into that and I’m kind of a book worm. Reading about gay life in 1960s New York, 1950s New York, particularly the world of hustlers and some of the bars, Stonewall and such, it was a lot of the outsiders of the queer community that gathered there. Then, some of the wealthy John’s who were there to meet the hustlers. I think Cowboy, out of all the characters in that play, is just the most used to everybody, because his version of New York includes the entire breadth of the community, so the birthday party for him is his birthday party.

Attitudes towards sex workers have shifted since 1968, although work still needs to be done – do you think the characters look down on him because of his profession?

I think it’s a combination of everything. I don’t think that it’s his profession entirely. I think there’s always been a little more understanding of tolerance and of acceptance of sex work in the gay community, the queer community. But no, I think he’s just sort of an alien. I don’t think he’s the kind of sex worker that they’re expecting.

Cowboy is another unique character. He doesn’t feel insecure about his sexuality or his profession…

I think he is. It’s sort of what I was saying a little bit ago about the scene he belongs to New York, and where he comes from. I mean, you have to get specific here. But, I think he’s just representative of what’s about to happen, in some ways. 1969 is when Stonewall explodes and the gay rights movement begins, and I think Cowboy is emblematic of that. He is the only character in a play who doesn’t have a name, who is open to and open with everyone about who he is and what he does, and has zero hangups. I think there’s something very sweet and special about that.

If Ryan Murphy proposed a spin-off for Cowboy, would you do it?

[Laughs] Obviously. Obviously! Cowboy and the John’s, I’m into it.

Why do you think the story of The Boys in the Band still resonates so well in 2020?

I think it’s the subject of shame. It certainly is the project of so many of our lives, as members of the LGBTQ+ community. How do we reckon with and overcome or not entirely live with our shame? And then, in what ways can we teach the human community at large about that experience and what it means, and how we deal with it? So, as long as there is any kind of marginalisation that happens in the world, a story like The Boys In The Band is a universal one. You’ve got these characters who have all of these different ways of trying to deal with their self-loathing and a lot of the time, it’s funny and beautiful and so… entertaining. What’s really beautiful about the play is halfway through, you see just how destructive living with that level of shame and self-hatred is, and anybody can connect to that story.

Ryan Murphy and his production company have hundreds of projects in the works at the moment – can we expect ‘Charlie Carver’ to appear in the credits for any of these?

[Laughs] No… And I couldn’t tell you if that were the case!

The first season of Ratched is now available to stream on Netflix. The Boys in the Band premieres 30 September.