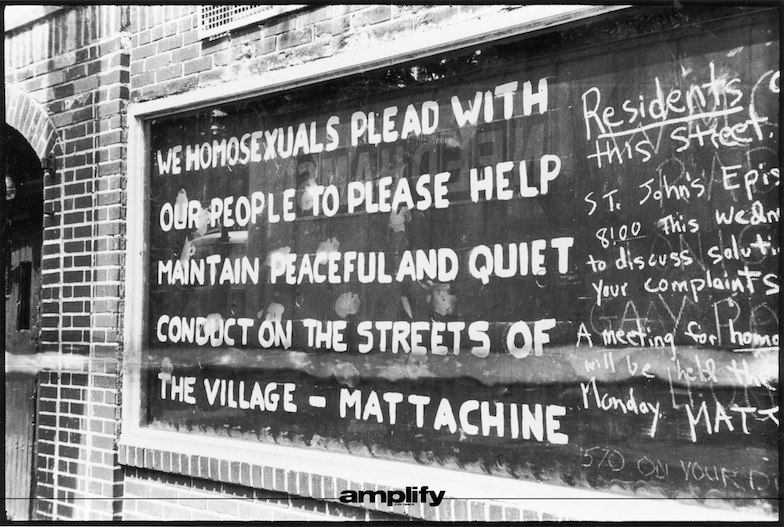

Chicago’s Society for Human Rights (1924) did not last long and was superseded by the Mattachine Society, founded by communist Harry Hay in Los Angeles in 1950, which spread across the country over the decade and is considered the first significant American gay rights group.

The Daughters of Bilitis, the first lesbian group (named after the fictional Sapphic character), started by partners Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon in 1955, was primarily a social safe space but became involved with the political struggle. Writers such as Gore Vidal, James Baldwin, Christopher Isherwood joined Radcliffe Hall in writing some of the only available fiction and would soon be joined by Audre Lorde and others.

In the UK, things were also changing. After high-profile prosecutions of Alan Turning, Lord Montagu of Beaulieu and actor John Gielgud, Sir John Wolfenden’s 1957 report lead to the Sexual Offences Act 1967 making it legal for two men over the age of 21 to have sex, strictly in private. (Lesbianism was not illegal).

During the 1960s more and more creative people expressed themselves. In the US, off Broadway theatre produced pioneering writers such as Robert Patrick and underground lesbian and gay theatrical collectives sprung up. In 1968, Mart Crowley had a breakout hit with his play The Boys In The Band about the struggles with self-esteem some gay men had, which would became a film in 1970.

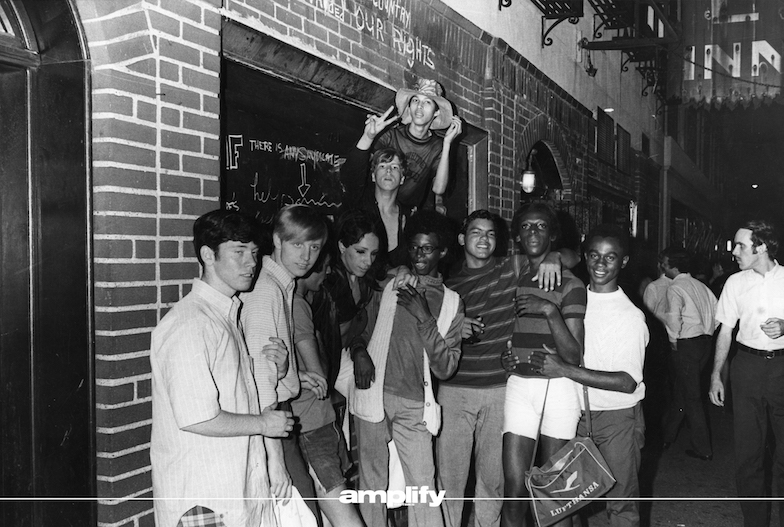

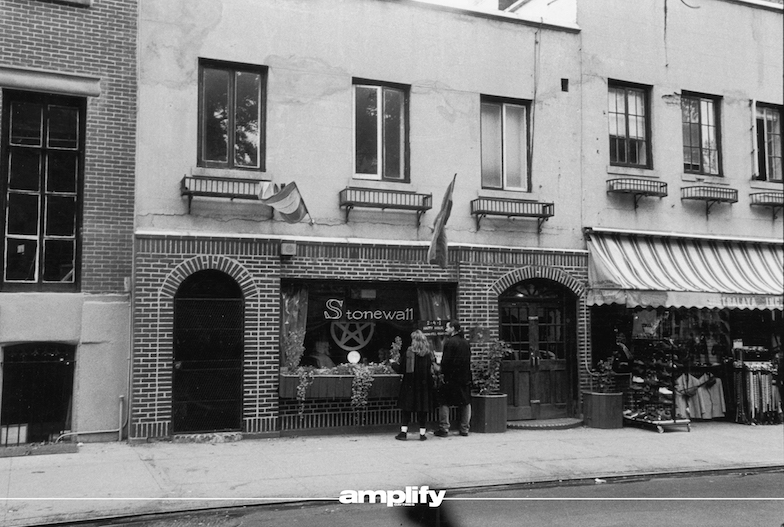

Then in Greenwich village in New York City, on the morning of June 28, 1969, the small mafia run gay bar, the Stonewall Inn – a haven for queer street kids, people of colour, trans and transvestites, people on the edge even of the gay community – was raided for the second time that week, something that was highly unusual, and the crowd fought back.

Craig Rodwell, a key activist, knew this was the galvanising moment they’d been waiting for. Rodwell and his partner, Fred Sargant, Brenda Howard (‘the mother of gay pride’) and others, organised a protest to commemorate the Stonewall uprising. On June 27, 1970, Chicago and LA both had marches and the day after, June 28, 1970, New York City held the Christopher Street Liberation Day, widely regarded as the first gay pride march.

In November 1970 a couple of hundred people marched through Highbury fields in North London. Then, on 1st July 1972, London had its first official gay pride march attended by 2000 people marching through London with signs such as ‘Homosexuals are revolting!’

Pop artists began to experiment with the boundaries of sex and gender identity. In 1972, David Bowie stated in an interview that he was bisexual and in 1976, Elton John, then the biggest star in the world, told Rolling Stone magazine he was too.

Culture was relaxing about sexuality and in turn was enriched by it. In 1977, two African American gay men changed the face of music. DJ’s Larry Levan and Frankie Knuckles were employed, Levan at the Paradise Garage in New York City and Knuckles at a new club, Warehouse, in Chicago. Both catered to specifically black and Latino gay and bisexual mixed crowds and the clubs became two of the most cutting edge in America, giving birth to Garage and House music. Over in London, inspired by these two clubs, entrepreneur Jeremy Norman opened the huge mega gay club Heaven in 1979.

And then out of nowhere, in 1981, reports of a rare cancer affecting predominately gay and bisexual men began to come out of America. By December 1981, deaths had been reported in UK and more across the world.

It’s impossible to express the devastation that AIDS brought, not just in the loss of lives of countless people, but also in the extreme homophobia that it unleashed.

The British media was particularly savage, hunting down and outing celebrities, judges, public figures, or indeed anyone. The Sun, under editor Kelvin McKenzie, lead the pack, relentlessly publishing quotes from a vicar, for instance, who said he would shoot his son if he had AIDS, and a deranged US psychologist who suggested that gays should be executed. By 1987 the British Social Attitudes survey found that 75% of the British public believed homosexuality to be ‘always’ or ‘mostly’ wrong. In 1988, having run a homophobic campaign, Mrs Thatcher’s newly re-elected government brought in legislation, Section 28, to outlaw ‘the promotion’ of homosexuality in schools, after The Sun found one teaching resource unit had one copy of a book called Jenny Lives With Eric and Martin, about a girl with two dads.

Out of this time came two vitally important groups. One was Stonewall, set up in 1989 by media and arts figures including actors Ian McKellen and Michael Cashman, Gay Switchboard’s Lisa Power and others. Middle class and respectable, it was intended to negotiate with politicians and the media in a language they understood. A year later, after the savage homophobic murder of actor Michael Booth in a public toilet, a group of activists including Simon Watney and Peter Tatchell formed an angrier, more protest and direct-action focused group called Outrage! Much was made of the divisions and which tactics worked best but both proved important: Outrage!’s protest forced politicians to engage with Stonewall.

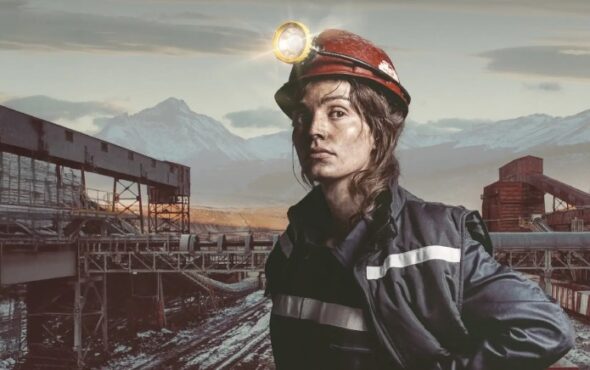

Eventually the Labour party committed to supporting lesbian and gay rights, as it was then, after a block vote from the National Union of Miners, due in part to the support given to them by the Lesbian and Gays Support the Miners group (as featured in the film Pride). Labour party leader Tony Blair attended the 1996 Stonewall Equality Show fundraiser, at which out pop stars such as Elton John and allies like Dawn French and Sting performed, a major moment.

After Blair’s win in 1997, much of the focus at the end of the 90s, in the UK, was on scrapping unjust laws such as the age of consent, Section 28, the armed forces ban and bringing in adoption and employment protection rights. Then came the push for civil partnership, the gender recognition act and, latterly, marriage.

In the US, with the slow progress and complications of the powerful religious right and individual state legislation, entertainment had a major impact. Queer filmmakers had been bringing arthouse work to the screen but 1993’s Philadelphia and 1994’s Mrs Doubtfire were two of the first mainstream films to present sympathetic depictions of gay characters. Comedian Ellen DeGeneres came out in real life and in her hit sitcom, Ellen, in 1997 – and her show was swiftly cancelled. Writers of a new show learnt from Ellen’s experience and created a sitcom about a gay lawyer and his best girlfriend. In 1998, Will & Grave became a ground-breaking sensation that Vice President Joe Biden credited with changing the views of the America public, as Ellen has done since her professional rebirth. The following year, in the UK, Russell T Davies produced the most controversial and direct TV depiction of gay lives on screen with Queer As Folk.

In the last 15 years, as marriage rights have become a focus around the (mostly) western world, the movement has begun to embrace the full spectrum, not just of lesbian and gays, but of bisexual and trans people and people with various other experiences. The erasure of trans, bi and people of colour has begun to be acknowledged. Stonewall heroes Stormé DeLarverie, Marsha P Johnson and Sylvia Riviera are beginning to be widely known, as trans icons such as Laverne Cox, Janet Mock and Chaz Bono have shot into the celebrity stratosphere. There is clearly far more to be done.

All over the world injustices continue, from the outlawing of gay sex in 70 countries to higher rates of HIV that LGBTQ people of colour still experience to the disproportionate mental health problems that can result from growing up in an invalidating society, something I cover in my book Straight Jacket. As we tackle some of these vital issues, things are taking a dangerous turn. Donald Trump and the rise of the far right across the world herald a new era of danger for LGBTQ rights. One key issue is the environmental crisis. The advances made are predicated on having a civilised society – one that Sir David Attenborough says is now under threat. As we mark the 50th anniversary of Stonewall it is clear that we must find inspiration in the activism of the past and recommit to stopping threats that may not seem specific to us. There are no LGBTQ rights on a broken planet. If climate breakdown continues as it is now, it will be petrol on the fire of the far right.

In the 60s people fought against the Vietnam war, for black civil rights, for the rights of women. Today we continue to fight for our rights and against racism and inequality here and across the world and have new challenges which must also be urgently addressed. I see the spirit of Stonewall in the queer people who are part of the new environmental protest group Extinction Rebellion. If we lose these fights, we stand to lose all that we have fought for.

An extended thanks to Getty Images and the respective photographers for use of the imagery seen above.

Pride: The Story of the LGBTQ Equality Movement by Matthew Todd is out now published by Carlton books.