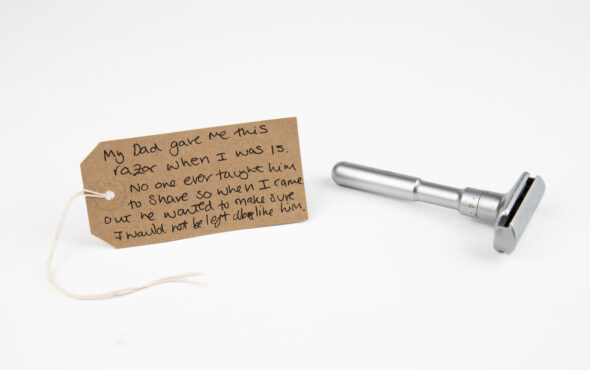

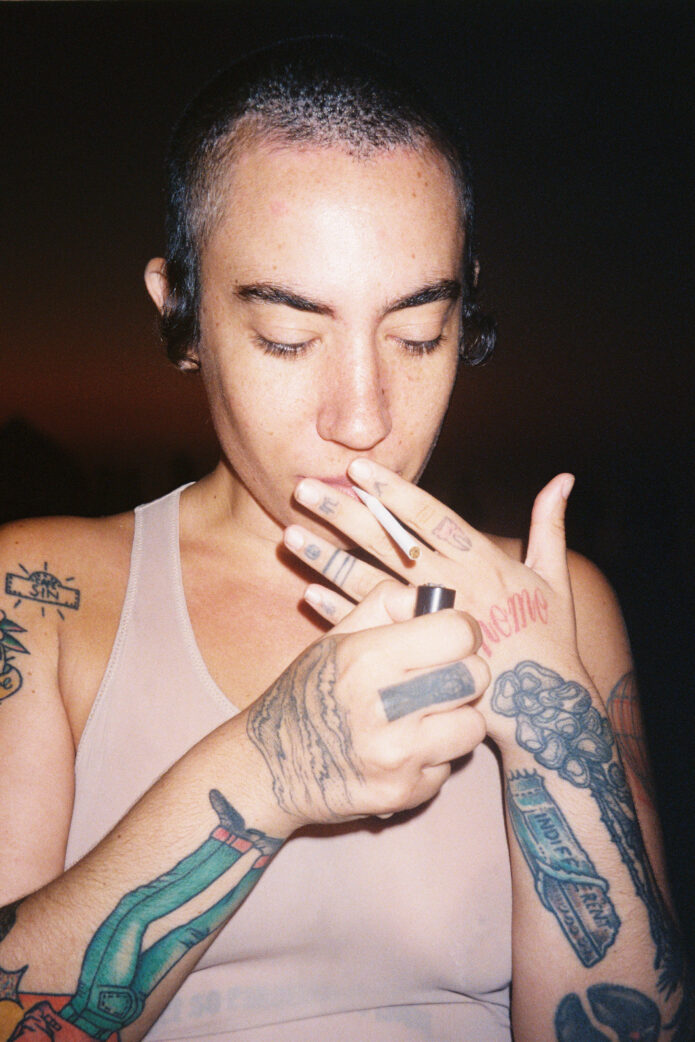

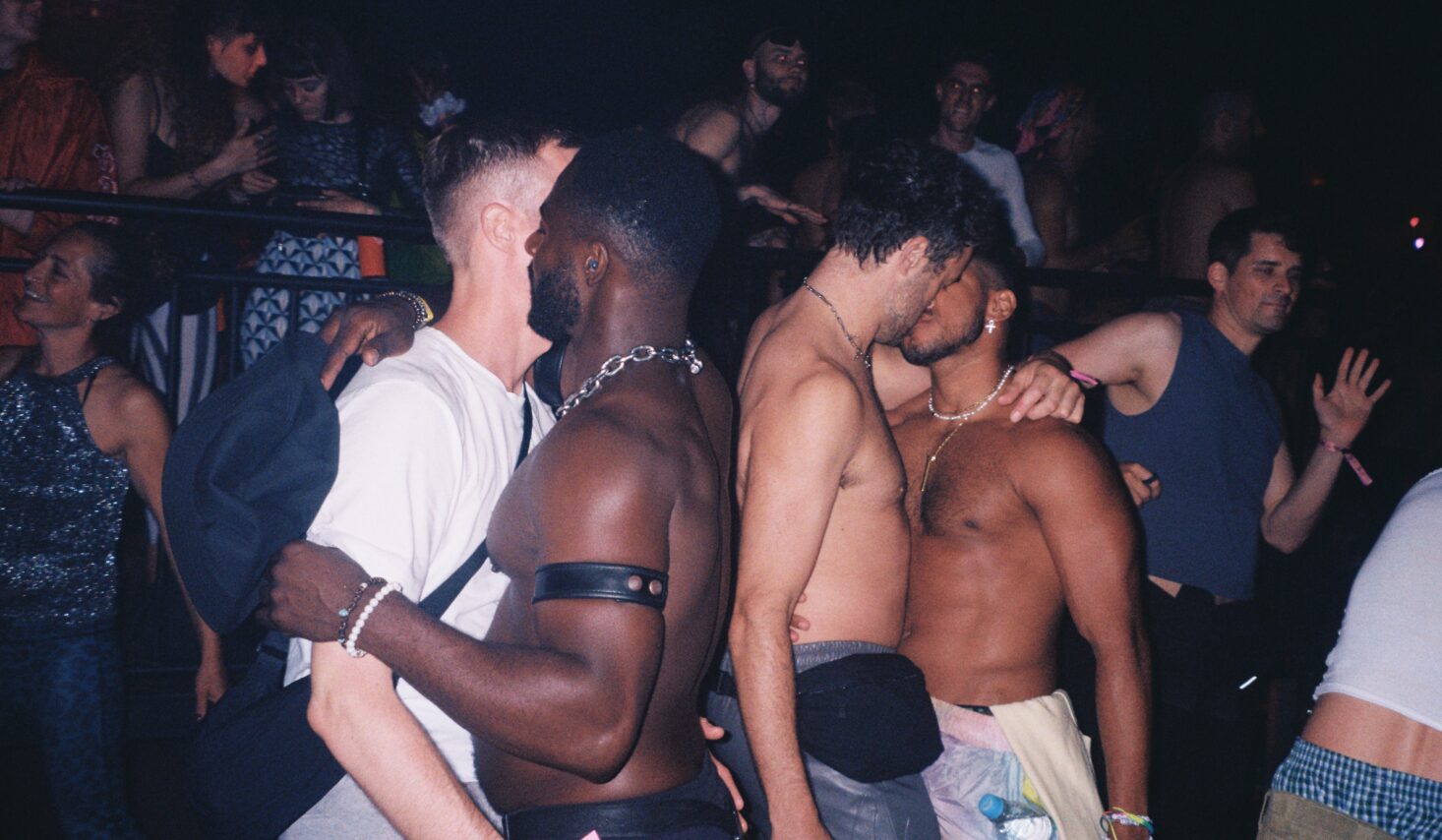

Tattooed limbs tangled together in bedsheets, anonymous couples kissing on the dance floor, partially nude bodies bent in different shapes across living room furniture. These are just a few of the scenarios included within Intertwined: the latest photobook from the Greek, Berlin-based photographer Spyros Rennt. Reflecting on themes of queer intimacy and interconnectedness, the project, as Rennt explains, depicts “bodies, emotions, and moments overlapping and blending into each other”.

A departure from the image-maker’s more explicitly erotic work, the project explores bonds of friendship and understanding that permeate the queer community. There’s also an implicit sense of trust and mutual respect between Rennt and his subjects, with the photographer’s honest gaze gently surveying his subjects in their most vulnerable moments — as they embrace a lover or regard the camera in various stats of undress.

Below, the photographer discusses this latest photo project, his experiences of Berlin queer culture, and the commercialisation of nightlife across the past decade.

First thing’s first, why did you decide to call this book Intertwined?

The title Intertwined felt right because the book is all about connection – bodies, emotions, and moments overlapping and blending into each other. My work has always been about intimacy, and with this book, I wanted to emphasise how relationships, friendships, and fleeting encounters all weave together to create something bigger. There’s also a strong physical aspect – I love shooting people in a way that their bodies merge, forming weird, almost sculptural shapes. That visual entanglement speaks directly to the title.

But beyond the physical, Intertwined also reflects something deeper: the way queer lives are inherently connected. Our fates, especially within our chosen family, are tied together – we support, shape, and carry each other through life. This sense of interdependence is something I feel deeply, and the book is a way of capturing that.

This latest phonebook serves as a departure from some of your more erotically charged work – how has this project evolved your perception and understanding of intimacy?

This book really reflects the mood and vibe I was in while creating it – I wanted to curate something that felt moody, even melancholic. That’s why it’s not as erotically charged as some of my previous work. I think it also shows a kind of evolution, maybe even maturity, in the way I approach intimacy. But that doesn’t mean I’ve left the erotic aspect behind – just that, for now, I was drawn to a different kind of emotional depth. Who knows what’s next?

Your work captures moments of closeness, hedonism and intimacy between individuals, how do you capture these moments without veering into voyeurism?

The people I photograph are either my friends or individuals who trust me and my vision. I don’t just walk into strangers’ bedrooms and start shooting intimate moments – there’s always a foundation of trust first. That makes all the difference. Once that connection is there, the process feels natural, collaborative, and organic rather than voyeuristic. It’s about capturing something real, not just observing from the outside.

"I don’t just walk into strangers’ bedrooms and start shooting intimate moments – there’s always a foundation of trust first"

Many of your images toy with ideas of anonymity, capturing bodies rather than faces. What is the thinking behind this creative decision?

For me, it’s more important to document the action rather than the individual – I don’t approach my work in a gossipy way. Focusing on bodies rather than faces shifts the attention to the feeling, the movement, the energy of the moment. Plus, anonymity makes the work more relatable and accessible – viewers can see themselves in the images, rather than feeling like they’re just looking at someone else’s life.

Your work is often associated with the dance floor – what is your relationship to nightlife and how does it inspire your work?

A lot of people associate my work with nightlife documentation, especially from my early years when I was constantly taking photos while going out. I don’t do it as much anymore, but I still love that kind of photography, and I’m really happy I captured those moments when I did. There’s something special about photographing people when they’re out – everyone is looking their best, feeling good, and fully present in the moment.

Nightlife also played a huge role in my personal connections – I met some of my best friends that way, and photography was a big part of bringing me closer to people. Beyond that, I’ve always felt connected to the underground and subcultural side of nightlife, which is where so much creativity, freedom, and self-expression thrive.

How do you think nightlife has changed since you first starting taking photos from the frontline of queer nightlife?

Talking about Berlin, where I’ve been based since 2011, I’d say the biggest change is that nightlife has gotten more expensive. I remember paying 6 euros for a 24-hour party back then, now it’s 20+ euros. That shift isn’t just about ticket prices; it reflects a broader change in the city.

I also feel like I meet fewer interesting people now. Back in the day, Berlin was full of these wild, unpredictable characters who were just existing, creating, and thriving without being tied down by conventional work structures. But with the rising cost of living, people need stable jobs just to afford to be here, which inevitably affects the kind of crowd you find in nightlife. There’s still amazing energy, but it’s different.

Berlin figures as something of an omnipresent character in your photography to date. What does the city mean to you, as a person and as an artist?

Moving to Berlin played a huge role in shaping my life, both as a person and as an artist. Honestly, I don’t think I would have become a photographer if I hadn’t been here. Berlin showed me that a completely different way of life is possible – where creativity can flow freely and without many of the restrictions you find elsewhere.

How I became a photographer was pretty organic: I knew I wanted to do something creative, and I also knew that the community and experiences I was having – whether at parties, on the streets, or in quieter moments – were so interesting and real. So, I just started documenting it. If I’d been in another city, I’m not sure I would have had that same drive or sense of urgency to capture what I was experiencing. Berlin really opened up that possibility for me.

Lastly, as a queer photographer, how do you think your work fits into a lineage of LGBTQIA+ image-making?

I definitely look up to and cherish the work of the great artists who came before me, like Nan Goldin, Wolfgang Tillmans, Ryan McGinley, and Walter Pfeiffer. Their work has been incredibly inspiring, not just in terms of the images they created, but in how they shaped a visual language for queer life and intimacy. It would be an honour to be following in those legacies, and I absolutely strive for it in my own work. At the same time, I hope to add something unique to the conversation and continue pushing the boundaries of how we see and represent queer experiences.