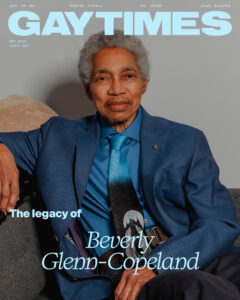

Beverly Glenn-Copeland’s biography up to 2020 reads like the epic journey of an artist-hero. Born in Philadelphia, United States, at the tail end of WWII to music-loving Quaker parents, he grew into a musically precocious child then came of age in 1960s Montreal, Canada, with a scholarship to study classical music at McGill University. Glenn-Copeland drew unwelcome attention there, not only as the first Black student in the music school, but also as McGill’s first openly queer Black (pre-transition) female student. Due to the hostility he was subjected to, he dropped out.

Glenn-Copeland then travelled to New York to study opera, released niche folk music recordings, discovered Buddhism, chanting and synthesisers, and embarked on a 25-year stint as a regular musical guest on Canadian children’s television show Mr. Dressup. During his TV tenure he recorded and self-released an experimental new age album in 1986 – Keyboard Fantasies – which sank immediately into obscurity despite its lush synth-driven iridescence. In the 2000s Glenn-Copeland transitioned and began living publicly as male, then shortly afterwards released an arresting album of baroque-electronic operatics and earthy percussion under the alias “Phynix”. That album more or less met the same fate as Keyboard Fantasies. Later that decade he reconnected with an old friend, Elizabeth, at a friend’s wedding. The spark ignited resulted in the two marrying not long afterwards, and the catalysing influence of this relationship is a consistent feature of Glenn-Copeland’s latter day work. “The quality of her love is humbling,” he says, nestled in a grey wingback chair in their temporary home in Hamilton, Canada. “She is a gifted writer, singer and theatre artist in her own right. She is my creative partner.”

In the 2010s Keyboard Fantasies was discovered by a renowned Japanese crate-digger who then emailed Glenn-Copeland out of the blue, seeking additional copies of the cassette tape. This brought about the eventual re-release of Keyboard Fantasies in 2016 via Toronto reissue label Invisible Editions, and the timing tapped directly into that decade’s musical vein for obscure ambient and new age music. Glenn-Copeland had finally achieved full-circle success, 50 years after the first of many setbacks that might have derailed another altogether. A cult following grew, as did the recognition and respect of influential young BIPoC and queer artists: Arca and Blood Orange have both engaged with his work. Being considered a queer elder is important to him. “This is an honour I do not take lightly,” he says. A satisfying denouement arrived in the form of the publicly-voted Heritage Prize at Canada’s Polaris Music awards in 2020.

As with the rest of the world, Glenn-Copeland’s immediate plans were turned upside down with the arrival of Covid-19. Unlike much of the world, however, in 2024 he is still stuck in a state of trying to urgently reestablish some normalcy. It is remarkable, then, that even with so many instances of progress-stunting circumstances across the decades that Glenn-Copeland continues to lead with capacious tenderness. While his musical references continue evolving from the bluesy longing of his experimental folk and soulful rock records, through the more minimalist electronic work of the 1980s, to his latest acclaimed album from 2023, The Ones Ahead, Glenn-Copeland remains – lyrically and thematically – in a state of reverent wonderment. While it boasts his broadest instrumental yet and increased production heft (thanks to the presence of his live touring ensemble Indigo Rising) The Ones Ahead resides comfortably in the intimate spaces between the personal, philosophical and natural worlds; the topography of the wilderness is a marvel, the ancient wisdoms of ancestors and animals are honoured, people meditate on the heaviness of existence, and soothe themselves and others near healing in bodies of water. Love, in Glenn-Copeland’s vocabulary, is always a verb. Even after my embarrassing timekeeping error that kept him waiting on Zoom for too long for our scheduled call, he radiated compassionate healing through a webcam once we connected. “You’re an incredible, sensitive person,” he beamed, towards the end of our conversation. ”I see that.”

This is not to suggest that Glenn-Copeland exists beatifically above or separate from human experience. Rather, he has a wisdom that allows him to access the sweetest marrow of life, no matter how demoralising it is to live at the mercy of an artist’s unpredictable life while navigating identity at the cross-section of multiple marginalisations. A quote from Glenn-Copeland’s website says: There are three challenges in my life. The first is being black in a white culture. The second is being transgendered in a hetero-normative culture. The third is being an artist in a business culture. In conversation, it’s the second identity marker that stings most. “Being transgender was not well received by some people,” he says. “In fact, one journalist accused me of doing it for attention. [It] was downright upsetting, with the journalist wanting me to explain the physical aspect of my transition in a way that was far too personal. I wanted to talk about identity. They wanted to talk about surgeries and hormones. In what world would it be ok to ask another human being about that?”

Glenn-Copeland credits the love of his wife, family and peers for seeding within him the fortitude and perspective to keep carrying on. “I had a solid base of love from my creative community and from my parents,” he says. “Even though they struggled with my queerness in my teens and early 20s, they made a solid foundation of love and respect for self that has never left me. Then, there are my lifelong friends and love relationships, people who have hung in with and for me in difficult times. Elizabeth, our daughter, her partner and our granddaughter. I have gratitude for essential health, for music, dance, poetry. Gratitude for the beauty of this earth, even though she is suffering. She gives us food, water, air and major doses of medicinal beauty daily.”

In their current season of compounded hardships, Glenn-Copeland and Elizabeth are facing crises of a material kind. “We got caught in a difficult time in 2020,” he says. “Our house in Sackville, New Brunswick, had sold and we were just about to buy our forever home. Then the pandemic hit, our tours were cancelled, and we suddenly found ourselves without income and homeless. We are in our fifth temporary home since 2020. Our big hope is for a forever home, here in Hamilton, Ontario, that we won’t have to move from ’til we are dead or have to go into long-term care. But we currently do not have the means to manifest home, so we are calling on universal energy for a bit of a miracle. We’ve had miracles before. [We want to] be able to continue to create. We both feel we came here for these times, and we still have so much to give. Music, musicals, plays, poetry, dance. We want to jam with the universe, and create lots of interesting works.”

As a now 80-year-old and immunocompromised person, Glenn-Copeland’s capacity to travel and perform have, presumably, an additional dimension of risk, and there are no extensive tours on the horizon. Despite the couple’s current precarity and uncertain future, the interconnectedness of queer legacies and the betterment of life’s cycles are a priority in Glenn-Copeland’s unique worldview, even if currently he is physically isolated and practically preoccupied with the inevitable next set of life’s worries to deal with. The Ones Ahead is dedicated, “to the generations that follow me,” he says. “I’m keen to be of service to ‘the ones ahead’. [Through] the deep pain of the incredible losses we’re facing, and the joy of living on this beautiful planet. I think it is critical for humans to make space for both on a daily basis.”

While reflecting on the life cycles of the album that eventually changed the course of his life, and on the sparse vocal and electronic ingredients that made it such an explorative listening experience, Glenn-Copeland is characteristically philosophical. “I wrote Keyboard Fantasies when I was living in the woods of Muskoka,” he recalls. “There is a deep simplicity to the woods. Repetition, clarity of image. All of this was given to me. When the cassette first came out, it mostly sold to parents who needed something to help put their children to sleep. Over the decades, this theme of easing tensions has continued. Last year, I received a note from a listener telling me that they played the track “Ever New” as their newborn was coming into the world. This made me cry. What an honour!”

This interview is taken from the May 2024 issue of GAY TIMES. Head to Apple News + for more exclusive features and interviews from the issue.