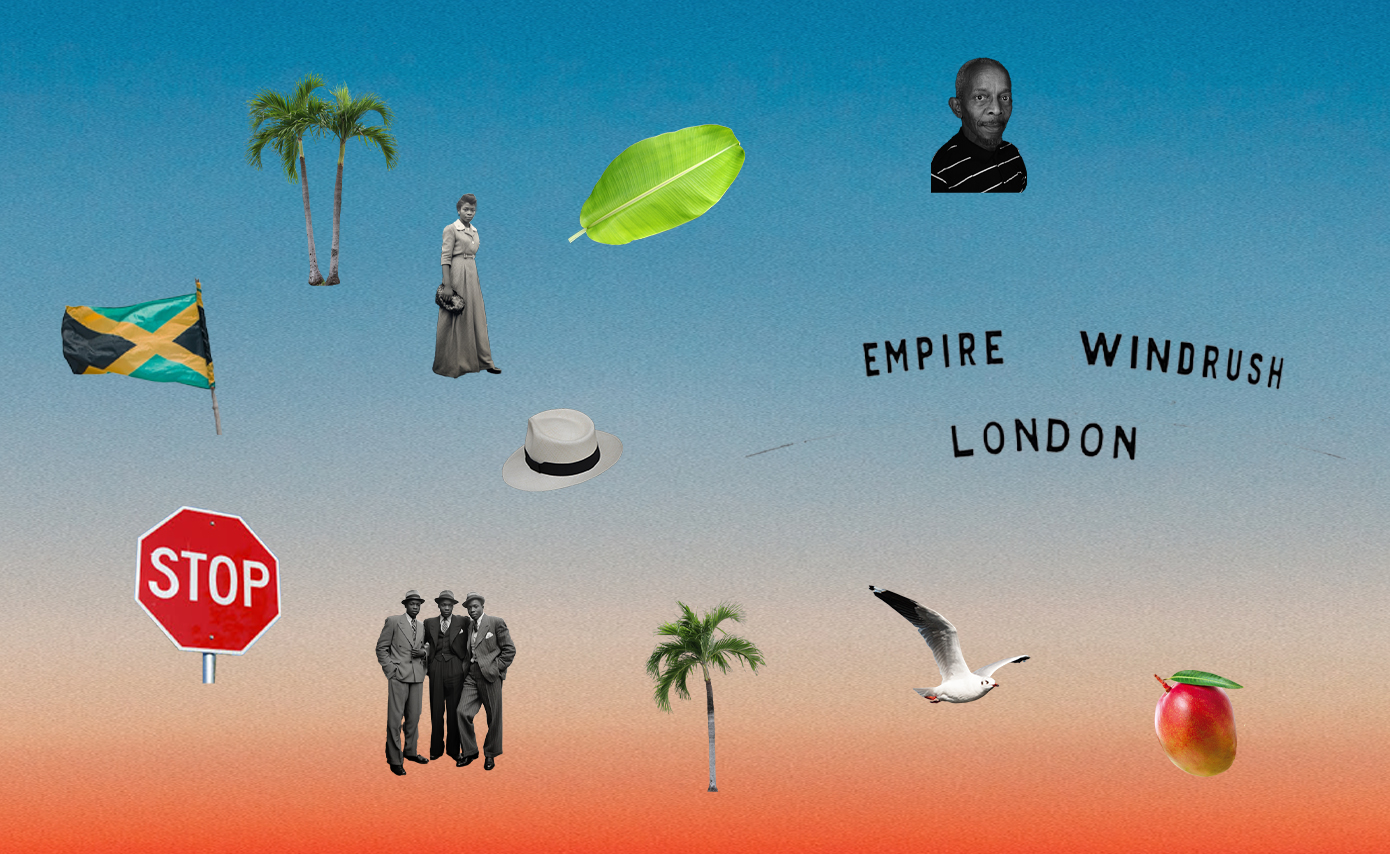

This year marks the 76th anniversary of the arrival of the HMT Windrush which docked in Tilbury, Essex in 1948. These dates are a reminder of the steady integration of Caribbean culture is woven into the fabric of Black Britain which has, historically, been well documented. However, still, among the stories of Windrush, there are plenty of Black LGBTQIA+ names that many of us don’t know. Ivor Cummings is just one of those.

Cummings, who has been described as the “gay father of the Windrush generation”, was of Sierra Leonean and British heritage and an openly gay Black government official born in Hartlepool in 1913, who welcomed the newcomers as they arrived in England. As a senior official in the welfare department of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, Cummings was in charge of organising transport and helping to find temporary accommodation for those who needed it. Beyond his official capacity, Cummings also stayed in touch with the arrivals once they had settled in the UK, regularly sending letters and receiving updates.

I first learned about Cummings while being asked to lend my voice to an episode of On the Record at The National Archives podcast about the Windrush generation. I was overwhelmed when I heard about Cummings. I was shocked that a story I know so well, as a Jamaican with relatives who arrived on the Windrush, involved an openly queer Black man. I was angry that I’d never been taught his name and that his story was one that I discovered by coincidence.

The arrival of the Windrush generation is a well-known story and the omission of Cummings from it is an example of the ways Black queer people have been cut out of key moments of history. Cumminngs’ role in helping people settle into their new life in the UK should be known outside of LGBTQIA+ circles and it shouldn’t be something you learn 76 years after the fact.

By misrepresenting Black queer British people in history, notable figures, movements and places are completely erased. Cummings’ voice was the first thing the new arrivals heard, and while the impact of the Windrush lives on, his name has been largely forgotten.

"Among the stories of Windrush, there are plenty of Black LGBTQIA+ names that many of us don’t know"

UK Black History Month has been celebrated every October for nearly three decades, and while it’s done a necessary job of spotlighting buried history, it’s fallen short of recognising the achievements of the Black LGBTQIA+ community in the UK. Over the decades, we’ve continued to see a focus on North American – not UK – history and wider straight culture.

Activist Marc Thompson argues that the LGBTQIA+ experience is regularly overlooked. “Black queer people are not seen in Black History Month, they are falling through the cracks,” Thompson, a co-director of the non-profit The Love Tank, explains.

As Thompson notes, this lack of education is hugely damaging. When I was coming out, before hashtags and social media celesbians, I turned to the internet searching for an image of queerness that looked like me. My painfully limited options were either Ellen DeGeneres or Jenny Schecter from The L Word, so, of course, I convinced myself that I was the only Black lesbian in England.

Years later, I stumbled upon articles about the Camden Black Lesbian Group, a centre that had existed near where I spent my weekends as a teenager. I soon realised that the community I was so desperately searching for had already been built for me, but I just didn’t know it. The requirement to seek out our own LGBTQIA+ history, and not be steered towards it, is disappointing.

For me, this lack of spotlighting further proved a political point – the stories of Black queer people in Britain, from the trivial to the trailblazing, have been sidelined in discussions of Black British history. And by overlooking these stories, we are only presented with a one-dimensional version of the facts, and we fail to learn the full story.

"The stories of Black queer people in Britain, from the trivial to the trailblazing, have been sidelined"

Queering Black British history

Author and journalist Paula Akpan experienced a similar feeling of frustration when she discovered that the Black Lesbian and Gay Centre (which was active throughout the 1980s and 1990s), set up to tackle the issues facing LGBTQIA+ people of colour, a short distance from her house in Peckham – something she had previously been unaware of.

“Every day I was walking around these spaces, not knowing the significance in my personal history and also in the history of a community that I’m a part of, it feels like you’ve been robbed of so much,” Akpan says.

Queer history is absent from the narrative of Black Britain for many reasons. But, as Akpan argues, one of the main culprits is the way that Black British queer people have been “marginalised” in the wider LGBTQIA+ movement and racial justice movements. For example, queer issues were often overlooked in Black activist spaces and the nuances of race weren’t paid attention to within LGBTQIA+ groups.

This was acknowledged by people of intersecting identities at the time, with Black and South Asian women describing the “invisibility of lesbians in the Black community” and “the lack of space” for racialised women in a 1984 article published in the Feminist Review.

Equally, there was also outright discrimination. One of the organisers of the UK’s first-ever Pride march, Black and gay activist Ted Brown, has even spoken about how he left the Gay London Police Monitoring Group (now Galop) following a confrontation with a white member of the group who used a racial slur.

And while Brown is among the most prominent names in the UK’s LGBTQIA+ rights movement, there will be countless other individuals who were sidelined in queer organisations due to the impact of racist attitudes like these – and whose stories haven’t been passed down. But even if they aren’t acknowledged in the history books today, that doesn’t mean the work Black queer people did in LGBTQIA+ activist groups wasn’t impactful.

Interestingly, Brown helped to set up Black Lesbians and Gays Against Media Homophobia (BLAGAMH), a group who launched a campaign lobbying Black British tabloid The Voice to apologise for its reports on Black gay footballer, Justin Fashanu.

Similarly, Akpan notes that Black queer women in the 1970s and 1980s also organised into more focused collectives, such as the Black Lesbian Group, where the nuances of their multifaceted identities could be appreciated and “they could stand by issues that dealt with Blackness and womanhood in a way that understood that they were overlapping and occurring simultaneously.”

"Queer issues were often overlooked in Black activist spaces and the nuances of race weren’t paid attention to within LGBTQIA+ groups"

Uncovering new narratives

But if we move away from traditional ways of documenting history, and instead look at oral history and ordinary people, Black queer stories can be found. For example, I recently discovered the incredible story of a safe haven for Black gay men in Brixton. Pearl Alcock was a bisexual Jamaican artist who ran an underground bar (or shebeen) in Brixton in the basement of her women’s clothing shop.

The shebeen, which later became a cafe, was a queer safe spot for many Black gay men who travelled from across London to have a drink and a dance, free from racism and homophobia. Alcock’s story has been preserved by the people who knew her and although some might not deem Alcock’s shebeen and cafe as activism, it’s an important part of London’s Black history which is being kept alive by ordinary people.

Similarly, both Akpan and Thompson acknowledge individuals who impacted the Black queer community in the day-to-day. “There were everyday actors who poured into that community,” says Akpan. “We don’t necessarily know their names, but we have their insight and we can build upon that.” As Thompson puts it, “people that just go about living their daily lives,” are “a part of history.”

In order to document perspectives like these, Thompson and writer Jason Okundaye created Black and Gay, Back in the Day: a digital archive and a podcast which documents the lives of Black queer people in Britain through photos submitted by the community. The project is focussed on counteracting the ways in which Black, queer experiences have been erased from celebrations of LGBTQIA+ History Month in the UK

“During LGBTQIA+ History Month in this country, the narratives, experiences and contributions of the Black, queer community are sorely missing and completely absent, apart from a few really well-known people.” Thompson explains. “We set up [the account] because we believe that Black, queer people are not recognised and seen in Black History Month and we weren’t seeing them in LGBTQIA+ History Month either. We wanted to fill that gap.”

Projects like Black and Gay, Back in the Day, mark a tide change: one where the role Black, queer people have played in history is finally being acknowledged. “I think the younger generation who are coming up are curious about the past,” Thompson explains. “What runs alongside that is an older generation who are ready to tell our stories.”

This intergenerational sharing of stories and experiences is how we can redress the absences, silences and gaps around the queer, Black community – people who have always been here, shaping history, but who have been overlooked for just as long. ‘‘We, as a community, are responsible for preserving our history,’ Thompson concludes. “To interpret, analyse, and share it.”’

Thompson’s right. Telling these stories is essential because they broaden the scope of the Black British history we think we know. Pearl Alcock’s life tells the story of Black queer nightlife, the work of Ivor Cummings goes behind the scenes of one of the most recognisable moments of Black British history and the legacy of Ted Brown’s activism shines a new light on the fight for LGBTQIA+ rights in the UK.

Black British queer history is Black history, it’s my history. I’m owed it, and we should know it.