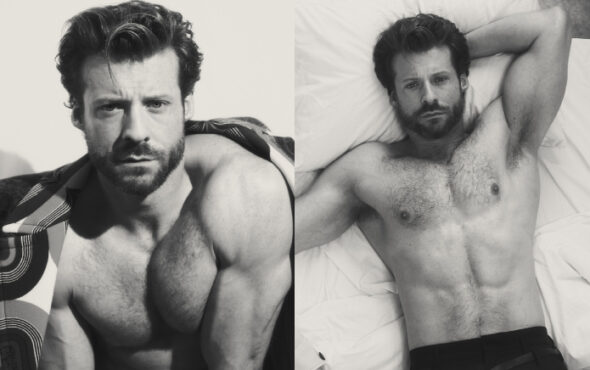

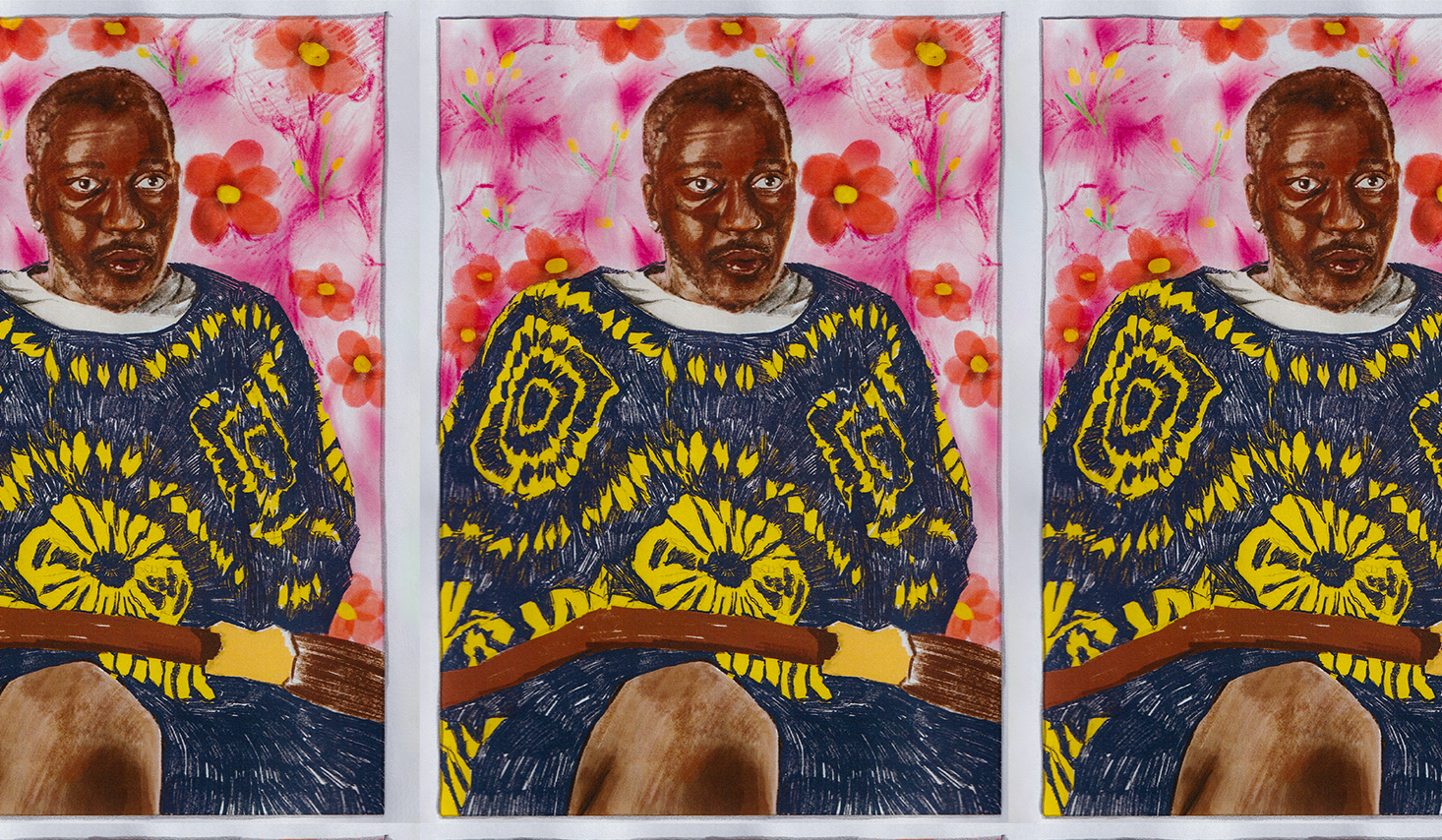

Anyone who thinks that polymaths don’t exist anymore probably hasn’t met Brontez Purnell. The Oakland-based novelist, musician, dancer, filmmaker, zine maker — and overall ‘pretty Black boy’ extraordinaire (to quote his interview with Steve Lacy) — can now add ‘poet’ and ‘memoirist’ to the list. Ten Bridges I’ve Burnt follows Pernell’s 2022 Lambda-winning novel, 100 Boyfriends. His new work is a captivating verse memoir full of his signature blend of sorrow, wit, and sex: “The most high-risk / homosexual behaviour / I engage in / is / simply existing“.

Careening from lyrical loving tributes to friends to searing excavations of inherited trauma, Ten Bridges I’ve Burnt is an uncompromising collection that explores thinking and working as a Black gay man across 20 years in the Bay, through dance studios, poetry conferences, bars, family houses, nighttime streets.

Purnell spoke to GAY TIMES about finding his style for Ten Bridges, looking for loneliness and self-love, and his expansive record collection.

You work across a large range of mediums and have three books out in the UK so far, but Ten Bridges I’ve Burnt is your first poetry collection – a ‘memoir in verse’, as the blurb bills it. What brought you to poetry?

It was a bit of a gamble – poetry just doesn’t sell as much as fiction – but I just really needed something else. Johnny Would You Love Me If My Dick Were Bigger got republished and it’s so crazy to me that a lot of people have read that now, this very specific snapshot of a very specific time in San Francisco that I wrote in my 20s; I’m glad I had the wherewithal to write about it then, because I think if I tried to write about those experiences now it’d be pretty watered down and boring, or maybe overly sentimental. But after that, and after 100 Boyfriends, I needed to rewire my brain about how to write about an excruciating amount of personal evaluation of memory. Memory is always this kind of fragmented archaeological dig. I think poetry is a really good way to deal with that, or to rewire the brain for it. My writing journey is a lot about me finding a way to fall in love with writing, this spouse that I chose, and I think every decade you have to find a new way to love somebody, to try to keep the magic new.

Where did your poetic style for the book come from?

Growing up I mostly read a lot of confessional poetry. My mother had the entire collection of Langston Hughes on the coffee table, so from the time I could start reading I read all of that. When I was in 9th grade my drama teacher gave me Nikki Giovanni’s Cotton Candy on a Rainy Day, I was probably a little too young but I could just about understand it. It was something wonderful, right? I also read The Bell Jar and Ariel when I was 12. Maybe that shouldn’t have happened, but I came from a very confessional Black and/or feminist concept. Then I worked through flash fiction, the 800-word short story, which lends itself to poetry really well. My style is an endless set of entry points, but that’s the best way I know how to condense it.

Oh, also, battle rap. I’ve always loved listening to Remy Ma freestyles [and] Connie Diamond freestyles. I think all poetry should have bars.

Ten Bridges is a very communal book, and cautious about the idea of getting subsumed into other people’s desires: ‘everyone wants my soul’. Poetry and memoir can both be reputed as quite solitary, but this book feels like it’s humming with the presence of other people.

Humans are very carnivorous, they feed off each other. I don’t know if there’s ever really a way to have space from people. My life has been very communal: I realised recently that I’ve never lived alone in my entire life. When I moved to Oakland I was in this house with 20 other kids, then with 12 people, then with 15 people, now I live with three other people, I don’t know if I’ve ever been truly alone. In order to feel alone it’s this really deep place I have to go to within myself. Maybe I like that place because physically I never actually get to be alone, so there’s something romantic about my loneliness for me.

But when it comes to ‘personal’ things, as well, I don’t believe that there is something so personal or so private that if you told someone about it a large, large group of people wouldn’t understand. We’ve spent all of language, from the beginning of time, mapping out the human experience – every quirk, every idiosyncrasy, every paranoid thought that we think we’re so alone with is actually shared by a lot of people.

There’s a really fun poem in the collection about writing for TV: ‘drama tends to surround me / so I decided to get paid for it’. It’s very clear-eyed and humorously cynical about creative work. How do you deal with that tension between knowing the pitfalls and drudgeries of that work, and still having to go show up and be enthused and get paid?

There is no way to love any job. Anything that becomes a job just feels like a chore – I used to complain about trimming weed for a living, but even when I trimmed weed I had one boss and one task. Now, living the dream of a freelance writer, work may come and may not, and I have 12 different people who get to yell at me about deadlines. It’s totally fine, but it does feel like when you get to these gilded positions that others are quite envious about, you often have that Wizard of Oz moment when you pull back the curtain and see that it’s just a bunch of guys pulling weird levers. Everything has felt like that, but it’s always nice to be brought down to scale. There is something comforting about the fact that everything is disappointing.

There’s a lot about your personal arc in Ten Bridges, but it’s also very tapped into specific gay subcultures, as all your work is. You’ve got some interesting gender stuff in there too, and you also mention Juliana Huxtable, you talk about the dolls. You’ve been writing for 20 years, so you’ve written through and within that period of trans people becoming more culturally visible. How’s that registered in your work?

Sometimes I feel like I’m watching the rest of the world catch up to things I and my friends have been talking about for 20 years. I remember when the only people who self-described as ‘queer’ were sex-working dykes in the Mission. The average gay dude in the Castro didn’t refer to himself as queer. I remember walking down Market Street, and this woman who hired me for her pot garden, she thought I was a lesbian…it was something like 2 weeks later in the pot garden and she was like ‘you’re a lesbian, right?’ And I was like, no, I’m a faggot, I have a dick. I’m a girl, but I have a dick… there’s always this realm of possibility.

Back when I was 25, young andro gay boys like me were called ‘dyke tykes’ and ‘tomboy fems.’ There was so much specificity of language then, and once people started using terms like ‘non-binary’, it actually erased a lot of intersectional language that had been used by the older guard. In some ways, it’s cool that the language changes, but I feel a lot of ways about the sort of McDonaldisation of various concepts, and the ways in which they can get turned against us in ways we never thought they would.

It’s cool that the language changes, but I feel a lot of ways about the sort of McDonaldisation of various concepts, and the ways in which they can get turned against us in ways we never thought they would.

At the end of the day, I think it’s better that the world is watching. But we pay a huge price for visibility. Being from Alabama, and from Black cotton field workers in Alabama, my father never went to school with white people, my mother didn’t go to school with white people until she was in her eleventh year of schooling. What’s happening with gender right now is essentially integration. Any Black Southerner will tell you the pitfalls of any integration movement. We always think it’s going to be this soaring utopic thing, and then for every step forward you take five steps back, and it’ll be like that continuously. Will we do the work? Of course we do, we have no choice, we do it or we die.

I really want to throw your books at some queer people who don’t understand how gay manhood has always included this element of fluidity and gender jeopardy. Your books are really thick with that understanding.

Being understood as a man was a thing that I had to fight to be, and I was born with a dick. The cult of masculinity is fucked up; men review each other’s manhood all the time, that’s where ‘faggot’ and ‘cuck’ come from. Who gets to be seen as this kind of virile masculine man? Not most of us. I think there’s the same thing with femininity – this whole capitalist cult of the unattainable. When I was in my 20s in San Francisco and believed that as long as I worked out at the gym for 5 hours a day and had the muscular body, I would finally win the boyfriend and the apartment. It was never about that. Oh, you have the nice body, but do you have a 9-inch dick? Oh, you have the nice body and the 9-inch dick, but do you have the 90,000 dollars in the bank account? It’s always about what you don’t have.

Looking for any type of mass acceptance is not going to happen. Society is not happy for any person who’s happy. As corny as it sounds, self-love is the hardest and most important thing. You can find acceptance from society well before you find self-love.

Finally, is there any music you’d recommend listening to while reading Ten Bridges I’ve Burnt?

I have two new records of my own out, one with Upset the Rhythm called Confirmed Bachelor, one called No Jack Swing, they’d make a good accompaniment, check those out! Aside from that, I love Brijean, they’re from LA, they’re the best band ever. Robert Johnson’s ‘Cross Road Blues’ would be good…and basically any Northern Soul compilation, as well.

Brontez Purnell’s Ten Bridges I’ve Burnt is out now with Cipher Press.