One year after its world premiere at Sundance Film Festival in January 2017, people are still talking about the story of an ethereal romance forming under an Italian summer in 1983.

But not all of the talk is positive. Criticism of Call Me By Your Name has swamped social media, and after the film was recently snubbed at the Golden Globes, it seems necessary to defend Luca Guadagnino’s elegant production.

So, without further ado: Here’s why all your criticisms of Call Me By Your Name are wrong.

1. The age gap

Related: Is a Call Me By Your Name sequel in the works?

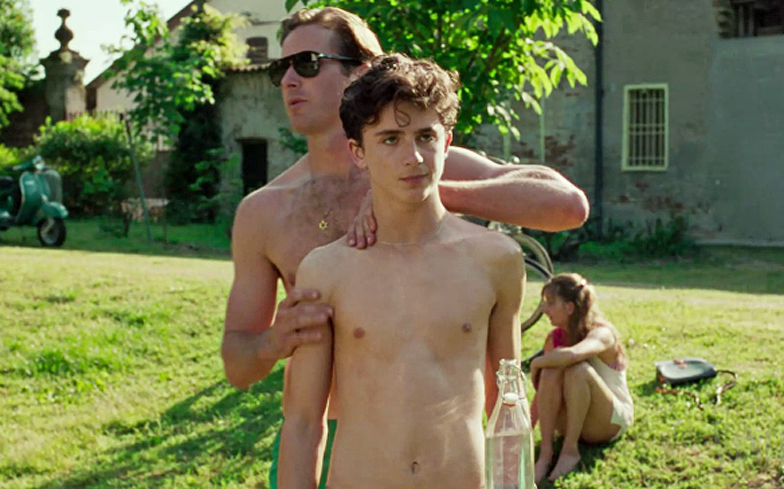

Without a doubt, the most ‘controversial’ subject of the film is the seven-year age gap between protagonist Elio, portrayed by Timothée Chalamet, and lover Oliver, portrayed by Armie Hammer. Elio is seventeen-years-old, three years above the legal age for consensual sex in Italy. In fact, the age of consent ranges from 14-16 in the majority of European countries.

The cultural norms surrounding sex are clearly established well before Elio and Oliver are intimate. For example, Elio proudly announces at the dinner table that he “nearly had sex last night,” to which his father replies, “Why didn’t you?” A question that suggests he trusts Elio is mature enough to make his own decisions regarding sex.

The trust his parents share is shown again by Elio’s parent’s acceptance of Oliver as their son’s lover. At the end of the film, Elio’s father reassures his son he shouldn’t regret his experience just because of the heartache he faces: “Right now, there’s sorrow, pain. Don’t kill it and with it the joy you’ve felt.”

Out of the rollercoaster of emotions that Elio is able to evoke, sometimes without even saying a word, regret is not one of them.

Sony Pictures

On the surface, Elio appears as a timid character that lacks confidence, and the concept that he seeks guidance in an older Oliver makes perfect sense, especially considering his first words about him are “he seems confident.”

But Elio exuberates confidence in other ways, ways which are subtle and internal yet powerful and admirable. He is the first to confess his feelings towards Oliver, fully aware of the societal repercussions it may have. “Because there’s no one else I can say this to but you,” he admits.

Elio makes many first moves, and without these actions, it’s possible the romance would’ve settled as a ‘skinny love’. He daringly grabs Oliver’s crotch; he reaches out and writes to Oliver after their slight distancing; he doesn’t deny his feelings when speaking to his father and he directly tells Oliver “I don’t want you to go.”

He bleeds, he cries, he laughs, he dances like nobody is watching and he wears his heart on his sleeve. Elio is far from weak.

Overall, their relationship is nothing more than legal and consensual, filled with reassurance and respect.

2. ‘Censoring’ gay sex

Little is left to the imagination during Elio’s anti-climatic sexual encounter with Marzia, portrayed by Esther Garrel. We’re shown his naked bum grinding awkwardly against her, which perfectly summarises their relationship: Public, experimental and emotionally stunted.

Elio introduces Marzia to his parent’s gay friends, making sure he kisses her in front of them. He brings up Marzia as an opportunity for sex at the dinner table and isn’t afraid to kiss her in public. But attempts to make his heterosexual relationship be known seem staged and uncomfortable.

When Elio and Oliver have sex, the camera pans out to the trees outside and the shot of rustling leaves holds for the longest still of nothingness in the film.

As viewers, we are given this length of time to not only think about what is happening, but to come to the realisation that there are significant differences between Elio and Marzia in comparison with Elio and Oliver, whose relationship is undoubtedly more sensual, delicate and pure.

Even the viewer cannot invade this precious moment that follows Oliver’s line: “Call me by your name, and I’ll call you by mine.”

Related: The love scenes from Call Me By Your Name have finally hit the internet

3. The absence of AIDS

Elio’s nose bleed, caused by anxiety, was interpreted by some as the character beginning to show symptoms of AIDS.

This lead to people expressing concern that the film doesn’t directly mention the issue of the disease and its consequences for gay and bisexual men, despite being set in the early 80s.

However, as Miguel Andrés Malagreca points out in his book Queer Italy: “The pandemic affected Italy later than the United States.

“Between the end of 1983 and the beginning of 1984, there was an activity in gay groups which tried to learn as much as possible about the disease.”

Additionally, the author argues “the first cases in Italy were reported in large cities with intense tourism” such as Rome and Milan, contrasting with the film’s rural setting in northern Italy.

Of course, AIDS and its invasive connotations would still be prevalent in the character’s lives, much like homophobia and its hostility.

But sometimes, actions can say a lot more than words. Just because AIDS isn’t embedded in the dialogue, it doesn’t mean it isn’t recognised by the characters.

The relationship’s foundation of caution and secrecy reveals the potential consequences of the romance which, fortunately, the characters don’t fall victim to.

There’s also something that needs to be said for Elio’s parent’s liberal view on sexuality and the acceptance they show their son and Oliver. Perhaps more conservative parents would’ve been more vocal in their concerns about AIDS.

4. Oh, the privilege?

White, middle-class characters bathing in the Italian summer outside their villa screams privilege – and there’s no hiding the fact that these characters have a lot to be grateful for.

But Elio and Oliver’s love for each other isn’t dependant on the luxuries of a bourgeois lifestyle. Arguably, it’s quite the opposite.

A theme of nature prevails throughout the story – dancing in the street, jumping into the river, cycling through the fields – the simplicity of the ‘free things in life’ is what provides the characters chance to escape and explore their relationship.

While it’s important to recognise privilege, and the consequences that come with it, arguing the film is classist is futile because the wealth of Elio’s family is neither relevant or influential to the development of their relationship.

5. Gay characters being played by straight actors

YouTube

One of the first things many of us did after watching the film was Google the main actors. If you didn’t, you should probably know: Elio and Oliver are played by two heterosexual actors.

Straight people playing gay characters can be problematic: There’s no denying the fact they haven’t experienced the same things we have, and sometimes this can mirror the believability of a film.

But when I watched Call Me By Your Name, I was persuaded I was witnessing two people fall in love.

Elio’s character development is intricately beautiful, and there’s something that unexpectedly resonates with his precocious and curious personality – even down to the exploration of his own body with a peach. Credit is due for the performance these incredible actors gave and for the message they’re communicating to a mainstream audience.

Producer Peter Spears tweeted: “10 yrs ago we set out to make the movie we needed when we were growing up, a great cinematic romance that challenged conventions and proved that love is love – that the magic, beauty and mystery of first love is something shared by all.”

Yes, of course, gay people playing gay characters is ideal, but criticising a movie that has the power to help so many people in our community is more important than the actor’s sexuality.

Films are subjective. What one person loves the other is bound to hate. In many ways, there is inevitably going to be a surface of critics when an LGBTQ film comes out – particularly as the representation of same-sex characters isn’t the best. But when we push for better representation we shouldn’t simultaneously tarnish gay films for their small imperfections, many of which are misunderstood.

Call Me By Your Name is the personal story of two characters. This is what gives the film its rawly human perspective. No, it’s not perfect – but it’s pretty damn close.

You can follow Liam on Twitter @LiamGilliver