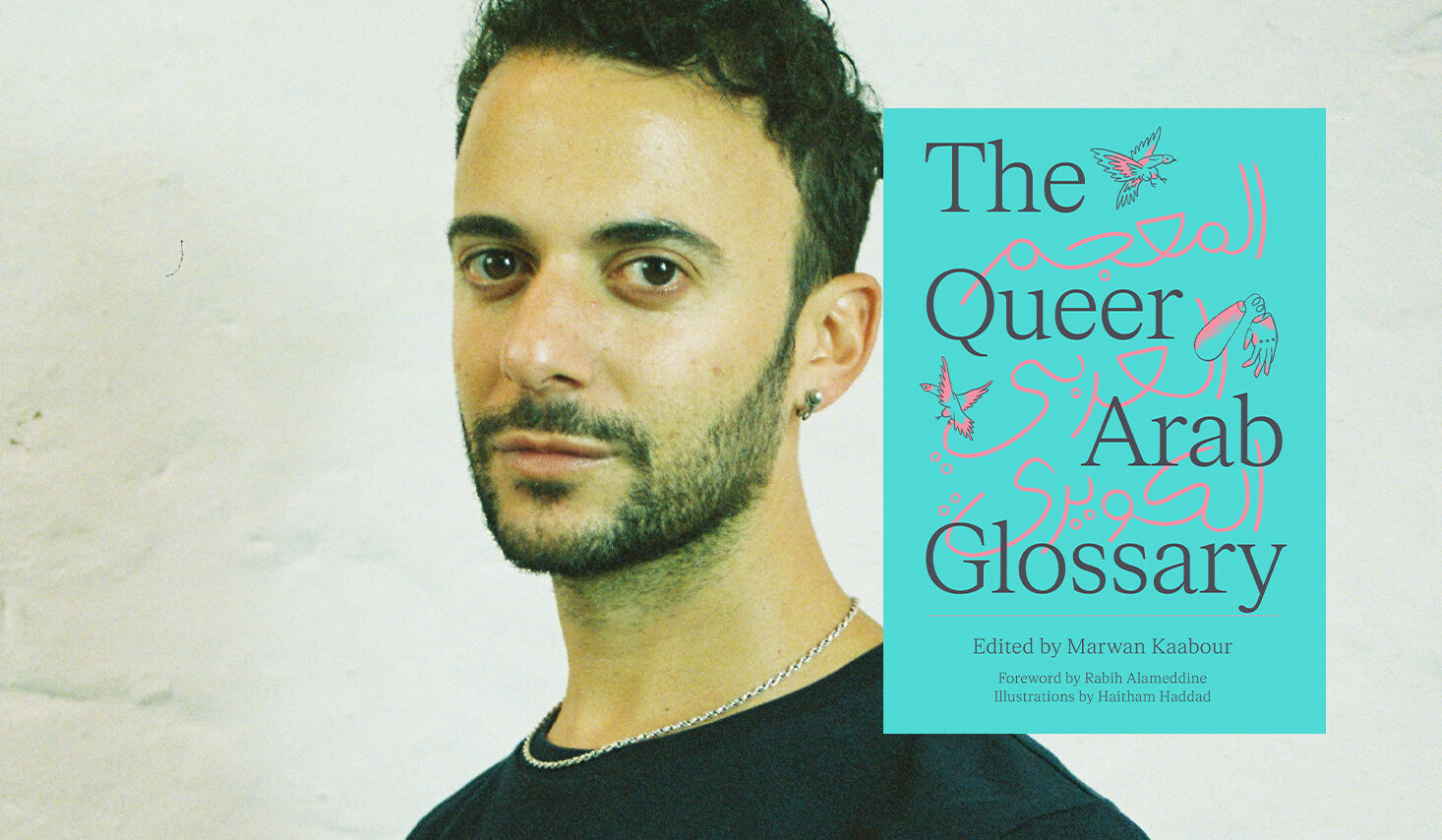

It’s not always safe to step into the world of queerness. Often, we wonder how our identities will be received, even just by being ourselves. And, sometimes, we don’t even have the means – the labels or terms – to express who we really are. We craft new words to bridge the gap between the words on our tongue and the identity we hold inside of us – and that is exactly what writer Marwan Kaabour addresses in his new book, The Queer Arab Glossary.

Historically, we have found ways to stay connected: bold flags denoting different identities, coloured hankies as a covert way of flagging sexual preferences, and, of course, speech. The queer community has resiliently regularly created its own language, out of necessity, and The Queer Arab Glossary explores this journey in the Arabic-speaking world.

A collection of LGBTQIA+ slang and idioms in different Arabic dialects, Kaabour’s project brings together a community of Arab voices — writers, artists, academics, and activists — to contribute to this thoroughly curated guide, where they explore the unique, humorous, and tongue-in-cheek aspects of queer Arab slang.

GAY TIMES spoke to Kaabour about how slang serves marginalised communities, the creative design of his debut book, and wants readers to learn from their journey into queer Arab lexicon.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Where did the inspiration for The Queer Arab Glossary come from?

The book is the first realised project to come out of Takweer, the [Instagram] platform I launched in 2019 that explores queer narratives in Arab history and popular culture. Takweer became a broad church of the queer Arab community, which represents the different communities, geographies, and cultures that form the “Arab World”. One of the main defining factors of being “Arab” is speaking Arabic. Despite the fact that all Arabs learn “standard Arabic” in school, very few of us actually use it in practice, but rather communicate in dialect. Arabic dialects vary massively from one part of the region to another. As Takweer and its audience grew, I began receiving messages from followers who spoke different dialects, and would use queer slang that I was sometimes familiar with, but often not. That triggered a curiosity to learn more about queer Arab slang, and soon enough I was organising hundreds of entries into a sprawling spreadsheet.

What is your favourite excerpt from your book and why?

The book is divided into two parts: The glossary and the essays. One of my favourite glossary entries comes from the Maghrebi (North Africa) section, and it’s Qaysou-l-ma’, which translates to “has been touched by water”. It implies that effeminate men have been “touched by water” which is the reason why they move in a fluid and swaying manner, or due to their “loose” mannerisms. Despite it being a slur, I found the analogy quite beautiful as it paints a picture of queer people as being singled out for being special enough to be “baptised” by (queer) water.

The eight essays in the second half of the book are all brilliant, but one detail I particularly love comes from researcher and writer Sophie Chamas’s essay, in which Sophie seems to be rallying the masses for a queer revolution:

“The glossary seems to say, we are deviants, but aren’t we all? If bottoming is deviance, if gender play is deviance, if effeminacy is deviance if promiscuity is deviance…? And if all of these things are also joy, are also pleasure, are also exhilaration, which is at the root of their being framed as immoral, as sinful, as evil…? If their being labelled deviant is an injunction to control oneself, to deprive oneself…? Then more power to the deviant”

The glossary hones in on dialects and essays as its focus. What drew you to those specific functions of language?

I think there’s a parallelism to be drawn between language, dialects and slang on one side and queerness on the other. They are both notions that escape limitation or strict definition and are in a constant state of flux. Their meaning evolves over time and is constantly challenged.

Slang and dialect are also ways for marginalised communities to innovate methods to speak about their own particular experience. Sometimes the linguistic tools that we inherit do not allow us to accurately speak about that experience, so we invent our own tools. Throughout history, different groups of people who operate outside of the mainstream have done this, in a similar way Polari has in Britain.

When it comes to the Arabic-speaking world, dialects vary massively from one region to another, and they don’t always abide by political borders. Each dialect is representative of the social, cultural and political context of that specific area, and so it becomes a window to better understand it. When it came to compiling The Queer Arab Glossary, sectioning the book by dialect rather than country seemed to be the most natural way.

As for the essays, they serve as a way to situate and contextualise the glossary and larger themes of language, slang and queerness within today’s world. The diverse area of expertise of each contributor allows the book to be expanded on in a multiplicity of directions, leaving the reader with a lot of illuminations, questions, and hopefully further curiosity.

What purpose do you hope this glossary will serve the LGBTQIA+ community?

I hope that The Queer Arab Glossary has an impact on multiple fronts. Accessible literature around the queer Arab experience has been historically limited to academic papers, gossip magazines, or relegated to footnotes. I hope my book can help populate the discourse and inspire additional contributions. Such references help queer people attain a sense of belonging.

I hope that this book can debunk the ludicrous myth, peddled by conservative elements of Arab society, of queerness being a Western import, while also debunking the other claim adopted by right-wing elements of the West that insinuates that Arab people are innately homophobic and are incapable of embracing queer people.

Finally, I would like to present this book as a challenge to Eurocentric queer discourse. For far too long we have adopted the singular Western way of going about queer liberation, attaining rights for our community, or even the way we express and manifest our queerness. This book shows a radically different form of queerness, and all queer people, not just Arabs, can learn from it. I hope this opens the doors for more similar contributions from the Global South.

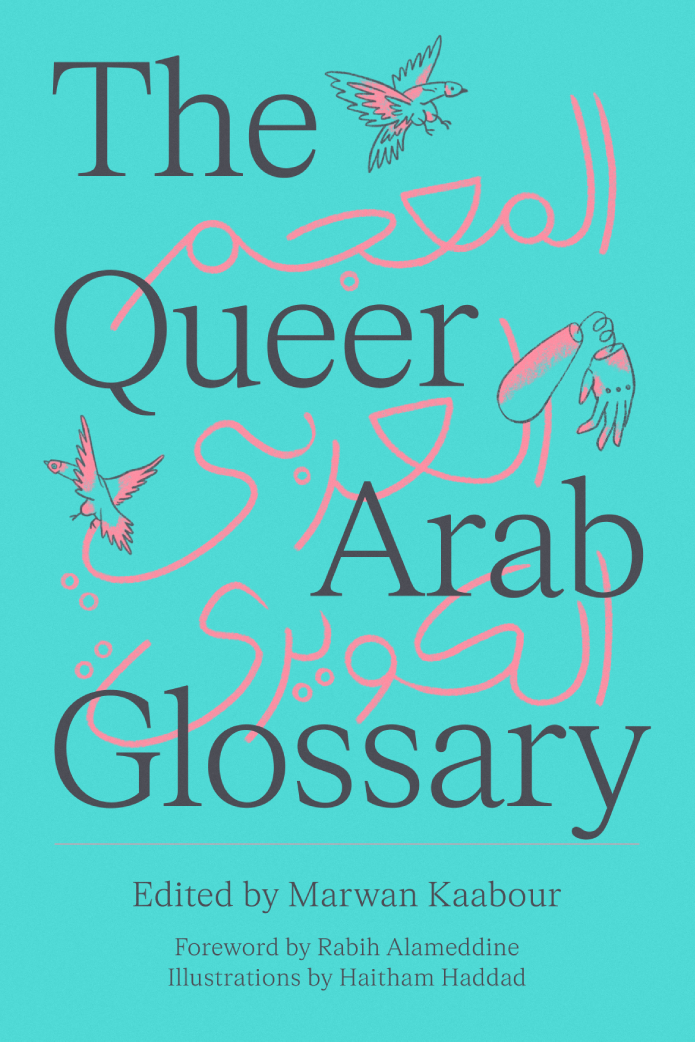

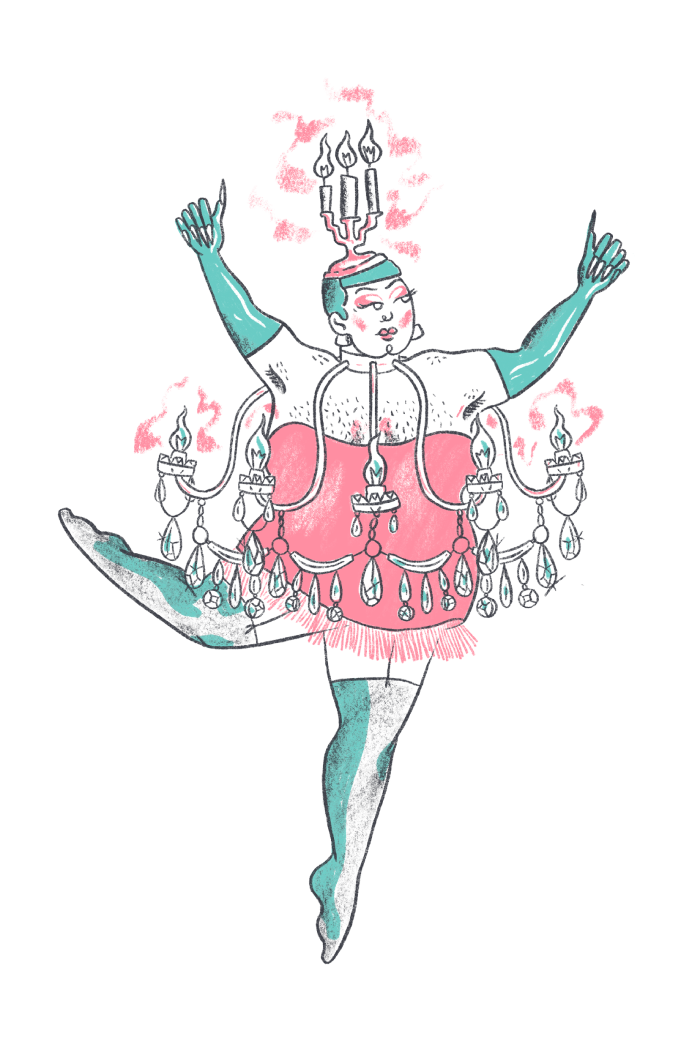

As a designer, can you share more about the significance of the illustrations in the book?

Over the last 15 years, I have designed over 20 books, from museum catalogues to cookbooks, artist books, and even The Rihanna Book [a 2019 visual autobiography of Rihanna, commissioned by Phaidon and Fenty]. Designing books is like writing a story or composing a song. You learn how to build the narrative and introduce elements of rhythm, tone, contrast, drama, harmony, etc. When I envisioned The Queer Arab Glossary, I immediately knew it needed to be illustrated, and for this, I knew I had to work with the brilliant Palestinian illustrator and tattoo artist Haitham Haddad, whose work I have been obsessed with for years. The idea was to visualise the personalities that the entries refer to, in an attempt to turn the toxicity that is embedded into a lot of these words into joy. We wanted to populate the queer Arab imaginary with queer mythological creatures, who are at ease with their sense of self. It is my hope that when a young queer kid picks up the book, they are able to see themselves in these characters and know that they too can feel that same joy.

We wanted to populate the queer Arab imaginary with queer mythological creatures, who are at ease with their sense of self

The glossary summarises a range of terms and personal essays from contributors. For you, how would you describe the feeling of completing your contribution (edits) to the book?

It’s a complex feeling. I was definitely overjoyed and proud that I was able to complete this ambitious project, but it was a long time coming and a long labour. By the time it was time to go to print, I was ready to let go. But nothing compares to the feeling of receiving that first advance copy. For a couple of months, I was carrying around the book like it’s my firstborn, proudly showing it off to friends. Now that the book is out in the world, it belongs to everyone, and there’s such beauty in that. I am able to learn so much about my own work via the reflections of those who engage with it, it gives the project an entire new lifespan. I am just at the beginning of this journey, but already gaging to see where it will take me!

Do you have a Pride message for our audience?

I ask everyone to reflect on their understanding of what it is to be queer. What’s the point of op-eds and pride marches, of diverse marketing campaigns and elected queer officials, when our trans kin are being bullied by governments, or when Palestinians are seen as disposable flesh? What are we fighting for exactly? As queer people, we need to be on the forefront of these battles, and not to get complacent. My message for the queer community is to go back to the revolutionary role of our movement that aims to uphold the humanity of all and secure liberation for all.

The Queer Arab Glossary by Marwan Kaabour, published by Saqi Books, is out now.