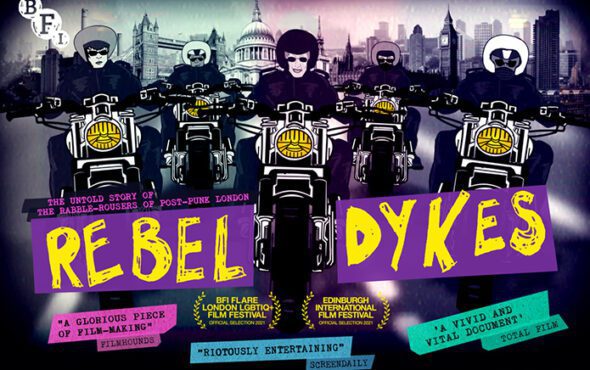

Leather-wearing lesbians may have been a minority in 1980s London, but one of the original “Rebel Dykes” hopes her documentary about the punk-loving subculture will bring LGBTQ+ people together across generational and political divides.

Siobhan Fahey expressed delight about younger LGBTQ+ people’s reaction to the film, which is coming out in British cinemas and online on Friday after festival screenings and an accompanying London exhibition that went viral on TikTok earlier this year.

“The reaction, particularly of young queers – and I’m talking about what you call Generation Z, the ones who are going to save the world, fabulous people – has been incredible,” said Fahey, 56, who produced “Rebel Dykes“.

“There’s been people crying, people saying they’ve been seen for the first time and they had no idea about this history,” she told the Thomson Reuters Foundation by phone.

“It’s great that people know these stories and … for older queers to meet young folk.”

“Rebel Dykes”, which Fahey made with directors Harri Shanahan and Sian Williams – who are in their 30s – after they attended one of her oral history events, joins other recent British documentaries and TV shows about LGBTQ+ life in the 80s.

“Mothers of the Revolution“, released last month, documents the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp, a protest camp against nuclear weapons that Fahey and many other lesbians attended in the early 80s, while “It’s A Sin” fictionalises the AIDS crisis.

Many LGBTQ+ people in Britain have expressed a hunger for such stories, saying discrimination kept them mostly off screens and often citing Section 28, a 1988-2003 law that banned local authorities from “promoting homosexuality”.

Protests against Section 28 feature in “Rebel Dykes”, including an interview with one of the lesbians who made headlines by abseiling into the chamber of Britain’s upper house of parliament after it voted in favour of the law.

OUTSIDERS

The film also tells the personal stories of a group of lesbians who lived together in abandoned houses, known as squats, in south London.

Fahey came up with the name “Rebel Dykes” to describe the subculture decades later with a friend in the pub.

“We used that to envelope all the outsider lesbians or dykes or whatever from the 1980s,” said Fahey, who arrived in London in 1983, aged 18, having been thrown out of home by her family.

“So that’s squatters and punks and reggae and soundsystems – you know, all of the ones that just didn’t fit? Sex workers and kink and … punk and all that. We all used to hang out together and it was good fun, us against the world.”

While the outcast lesbians became one another’s family, there were also struggles, including hunger, poverty and drug addiction, said Fahey, who was a sex worker “on and off” until she moved to Scotland in 1991 to train as a nurse.

The “Rebel Dykes” also had to contend with opposition from other women to their transgender-inclusive club night “Chain Reaction”, as they saw the sadomasochistic sex theme as perpetuating male violence against women.

“Queers and dykes of all generations have suffered massive trauma,” said Fahey, reflecting on the disagreements that have taken place within the community over the decades. “I hope that our project brings people together.”

“The film is about community and having a laugh,” she said. “One of the directors, Harri, says ‘queer joy is a form of queer resistance’, and I think that’s lovely.”

Reporting by Rachel Savage.

GAY TIMES and Openly/Thomson Reuters Foundation are working together to deliver leading LGBTQ+ news to a global audience.