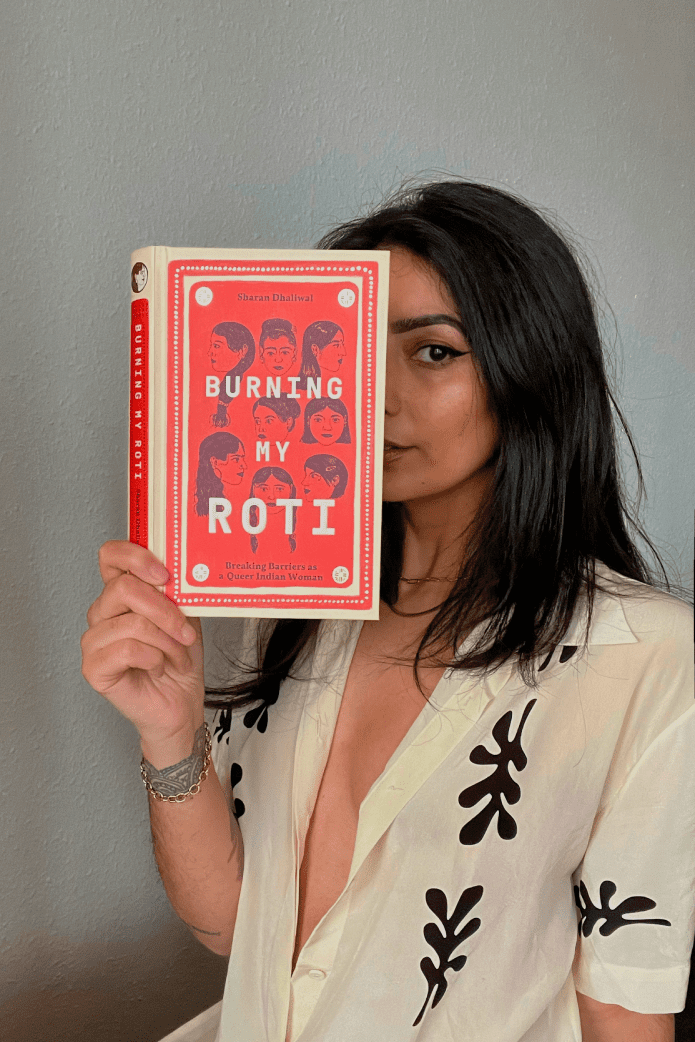

Sharan Dhaliwal, the founder of South Asian publication Burnt Roti, has established a career creatively dissecting subjects on culture, queerness and womanhood. In her debut book Burning My Roti: Breaking Barriers as a Queer Indian Woman, the journalist-turned-author introspectively dives into the facets that make her whole.

Taking an honest look at her queer coming of age experiences, colourism, and her own navigation of British-Indian cultural intersections, readers are greeted with a memoir-meets-guidance book. Packed with stories and conversations guided by Sharan, the author reveals that it was South Asian women that brought this book to life: “The team behind the book are all South Asian women and that’s something that I really appreciated. Burning My Roti wouldn’t look the way it does without any of them.” And in this collaborative effort, a work hemmed together by the support of women, Dhaliwal wears her emotions on her sleeve as she guides the audience through conversations with family, friends and self-reflection.

With her new memoir readily available, GAY TIMES interviewed Sharan Dhaliwal to hear more about how Burning My Roti came about, writing in lockdown, and why inclusive representation in the publishing industry is overdue.

Hello! Congratulations on the release of your debut book Burning My Roti. What’s the reaction to the launch been like?

It’s been really great to hear people saying things like it’s nice to have a book like Burning My Roti out. It’s only gone out to a handful of people really at the moment, but it’s more knowing that it’s out there and that there is a sense of happiness around the fact that it exists. It has been really well received and it’s nice to hear those little messages from people.

You write a lot of Burning My Roti during lockdown. What was this process like for you?

It was a form of therapy that I really needed at the time. A lot of the conversations I have in the book are internal and external conversations. The signing of the book was during lockdown, but the idea was conceived a couple of years before. This agent approached me and said they would like to read something about you your story and Burnt Roti and it kind of evolved from that. So, the book became an evolution of the conversations I’ve had over the years with Burnt Roti and the things I’ve been learning. I created Burnt Roti to learn more about South Asian culture, religion, communities and my own queerness, so writing the book was a track of that journey.

Throughout Burning My Roti you’ve blended an engaging visual style with anecdotes, mini-essays and passages of text. Why did you opt for that style?

There’s an illustrator Aleesha Nandhra and she’s just amazing. A lot of the conversations were had while she was drawing, including the cover as well. This book is like me telling my story as well as other people as well speaking. I don’t want it to be singular. I don’t want it to be one representation of one idea. We wanted it to have a bunch of South Asian people on the cover and representative is possible without being stereotypical. There’s this really old Indian matchbook kind of illustration style and I wanted to incorporate that design. When visiting India, as a child, and seeing hand-painted art all around me and on trucks or billboards that had always kind of sat in my head. So, when I saw Aleesha’s work and I knew that’s exactly how I wanted it to look.

Burning My Roti is sectioned into chapters where you unpack different topics, sometimes with yourself and other times in conversations with others. What was an important lesson you learned from writing this book?

The writing was cathartic, but within my own understanding of my identity, there was there’s still a lot missing. It was nice to write down something in the now, but knowing that the whole idea of it is still is a question mark. It’s an interesting ongoing journey. I’ve stopped calling myself bisexual and I just say queer now and I don’t know if I would have come to that conclusion since the book. I am still questioning so many things because I don’t really want to associate my sexuality with my history. It really stifles your ability to explore when you just stick to a history you have. Maybe it was forced heterosexuality and I’m still unsure about the way that I would define myself, but I’m also quite happy with not having a full definition.

I’ve stopped calling myself bisexual and I just say queer now and I don’t know if I would have come to that conclusion since the book.

One of the reasons I didn’t come out until I was 34 was because I wasn’t aware of it so I lacked that in representation. Take Bend it like Beckham’s “I thought she was a Pisces”. I didn’t know there was any queer South Asian representation that I could see and have an internal conversation about that. There was a fair amount of South Asian representation in the sense we all watched Bollywood and Indian soaps at home. It’s our culture was ingrained in the way that we grew up, but it was when we left our home and then the representation suddenly lacked. I do think it’s so much more prevalent now. It’s amazing how much I see now. I love it. It would have been nice for us to all have had compassion and empathy for humanity in the sense that we would have been welcoming of all people, because we haven’t lived in that kind of society. So our progress is something to be celebrated.

We’ve seen that the publishing industry has a statistically low figure of non-white writers within the industry. Do you think Burning My Roti will is participating in creating spacing for more representative writers in the field?

I think it’s interesting. It’s not a straightforward answer. You will see this boom of loads of books by people of colour coming out. Loads of people got signed during the first lockdown and what’s happening is that [publishers] all realised that they are being noticed so they have started to fill quotas and all these authors that are queer, non-binary, trans writers are doing so well right now, which is great because those voices get out and their books now exist. These people now have platforms and they get to talk about their experiences. It’s great that it’s happening, but it doesn’t stop the publishing industry from being racist. We still have a lot of things going on.

Queer, non-binary, trans writers are doing so well right now, which is great because those voices get out and their books now exist

The publishing industry is still going around in this circle of power and money and carelessly throwing women of colour under the bus. The industry is not really contributing to a conversation about anti-racism, they’re contributing to racist ideology, and that’s still within the institute of publishing. It’s just because I’m in it. I’ve just noticed it a lot more. The publishing industry is giving people more voices, but it is inherently, still racist and will be until the idea of the power structure is redefined.

What do you hope readers from the LGBTQ+ South Asian community take away from this book?

I want Burning My Roti to be something that will empower someone to say well ‘now I’m going to write about my shit now as well’. They know there are books of queer South Asian women out there, but now they can feel like they can write and share theirs too. I want to read everyone else’s stories.

Burning My Roti is now available via Hardie Grant Publishing and can be bought here.