“I know you don’t have a lot of time. So first . . . I’m going to spit out my gum.”

I wondered why I was saying this. I was stalling and it was only drawing attention to my uneasy hands and the fact that I knew there was nothing in my jacket to spit my gum into. My nerves were making me stupid.

As I fumbled for pretend napkins inside of empty pockets, I heard my artistic hero and all-time idol fill the pointless time that I was making us live in, “My mother was always so anti-gum.”

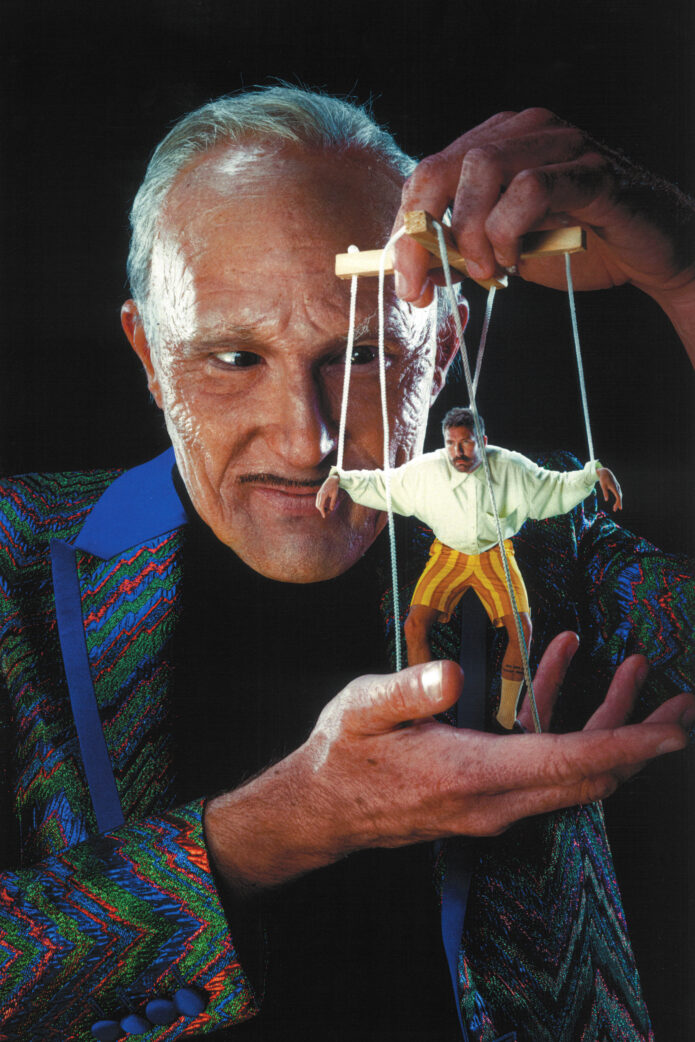

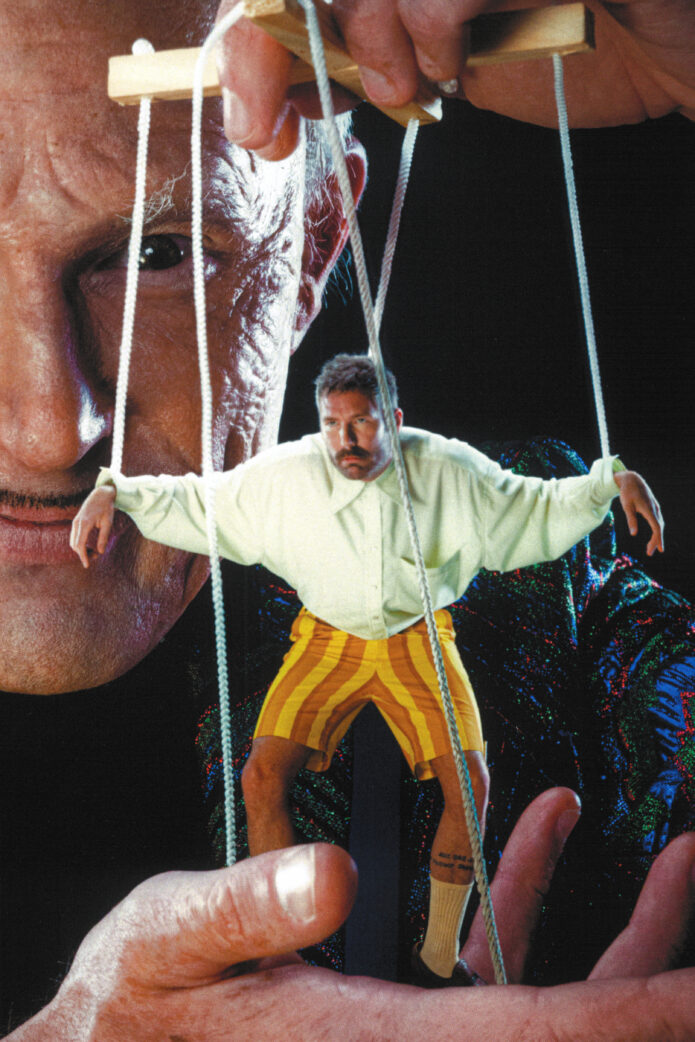

“Are you anti-gum?” I asked, afraid that I might already be disappointing him. This was confirmed with a simple, “Yes.” I apologized as my fingers dug through my wallet, finding the perfect FedEx receipt for tired gum. It rested next to an eight-year-old business card that had not left my pants since the day it was bestowed upon me by the man who I was now sitting across from: John Waters.

Eight years ago, I had tapped him on the shoulder at a gallery in Provincetown while a dozen gay men perused art made out of license plates. I invited him to a screening of my film at the festival that night. He declined, having already made plans, and handed me his business card as a parting gift. Had he known at the time that I would spend the next few years using that business card to persistently email him with requests to watch my feature, watch my TV show, be in my TV show, and to meet with me, see me, know me, talk to me, and love me, he might have thought twice.

The people who meant something to us when we were young will always be holy. When I meet a famous person today who wasn’t on my radar until adulthood, they typically hold no magic over me. There is, however, a shortlist of giants whom I revered in my youth that deeply paralyze me should I find myself in their presence. John Waters is, was, and always will be my number one. And for that reason, I will never be able to prove to him that I can be funny or cool or fun.

I’m not delusional. I know John Waters isn’t just mine. He’s for everyone. His work has shaped the hearts and minds of thousands of queer kids for years and I am but one of them. I will say, though, that there is something extra special about having artistic idols for the kids who have dreams of going into show business. One day, they might even meet, work with, or become just like their idols.

My younger self knew one thing for sure: One day, I would become John Waters. And why wouldn’t I? We have to be spiritual kin. We both love big characters. We both love exaggerating life until it feels more like life than life does. We both love making people feel uncomfortable to serve some personal and artistic crusade. We’re both gay. We’re both six foot two. And even our names sound kind of similar if you say them back-to-back over and over and over. Not that I have.

The chicken and the egg with having role models is that I’ll never know how much of myself I owe to his influence, and how much is authentically me. All I know is that there is a lot of John Waters in Charles Rogers, and even though there is plenty about myself that I struggle to love, I know that I love that part, because I love him.

But here I was sitting in front of him in his Baltimore home as Charles Rogers. I was somehow still not John Waters. My life had taken turns I could never have expected. I had lived a lot of life since he handed me that business card almost a decade ago. I had moved from New York to Los Angeles at twenty-six, and by twenty-eight, I had created a television series called Search Party that was the lens through which I lived my entire life. Over the next chapter, I fell in big love, found a community of fun people that seemed to double by the year, traveled everywhere, threw parties, and took for granted that everyone was healthy. As my twenties closed in a flood of abundance, the tides gradually receded. The big love turned bad. The pandemic scattered my people. The fun changed. My show came to an end. My dad died.

My life is different now. The train arrived at the station after a years-long journey and now I try to make sense of the pain, glory, and chaos of the entire ride. I trust that another train is coming soon, but if I don’t get to the bottom of who I am and what I want while my soul is still cracked wide open, then the pain will all have been in vain and I won’t deserve a new train. I will die at this station, forever obsessing about that one ride.

I had come to my hero for advice, real life advice about my own real life. If the man who lives full-time inside my soul can’t fix me, who can?

The chicken and the egg with having role models is that I’ll never know how much of myself I owe to his influence, and how much is authentically me.

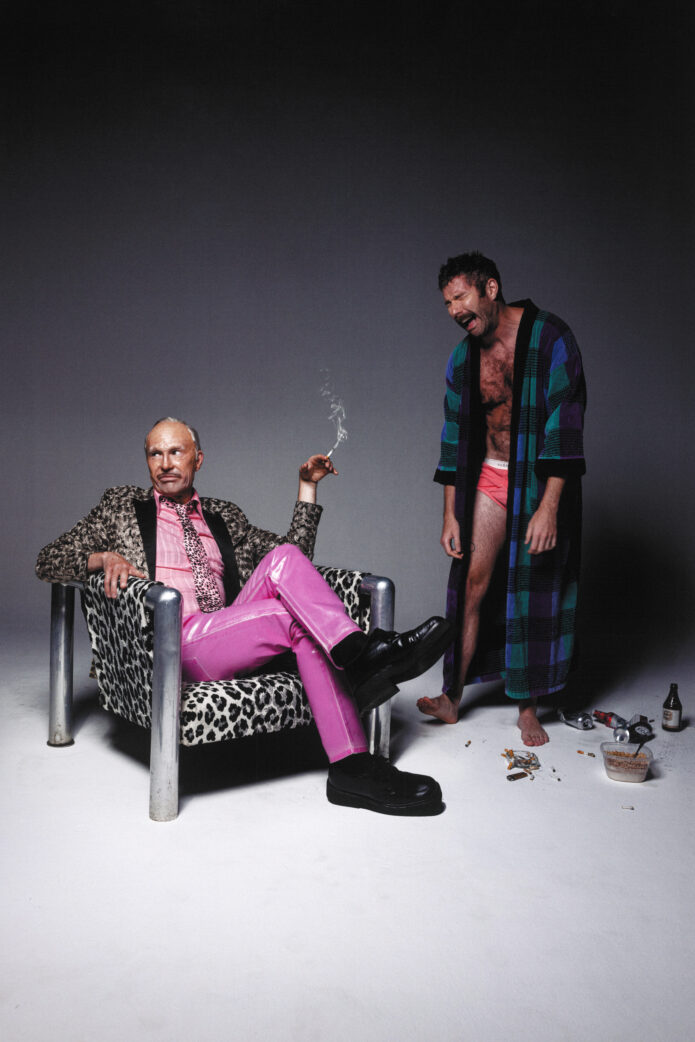

John Waters is someone who knows who he is. He knows what he wants. He is who I still wish I could become . . . and there’s still time to try. So as I folded the FedEx receipt around my gum, I relayed the tired list of tragedies that shaped my last few years—the descent into madness that was the end of my last relationship, the dissociation and hysteria that was my dad’s death, the fog that is my present, the mystery that is my future.

I wanted advice as loud and as ceremonious as the pain that delivered me here. I wanted a queer elder who could anoint me worthy of my next chapter. I wanted it so badly that I flew myself from Los Angeles to Baltimore to steal what little time he could give me, asking him questions in his own home. I was in my idol’s actual home.

I couldn’t even relish in the gravity of this fact—I could only focus on the difference in our homes. My house in Los Angeles is bright, postmodern, and circusy. John’s house in Baltimore is sophisticated and cave-like. The lighting is warm, the art is real, and there are thousands of books for people who actually read. This difference was a red flag that I may not have become John Waters. He was doing Europe, and I was doing Hollywood. I would have to sell everything.

He absorbed my woesome bullet points; a sweetness in his eyes. For all of the devilishness of his persona, he’s just as collected, intellectual, and empathetic. You can tell that he’s a good person. He leaned in, seemingly ready to impart the wisdom that would finally deliver my soul unto itself, “I’ve gone through every single thing that you just told me happened.”

I nodded along, prepared for a conveyor belt of answers and relief. He continued, “I’ve been in relationships that ended badly. I have been unable to get a movie made. I have made movies that failed at the box office. Both my parents died, but they were ninety years old. It wasn’t tragic. I mean, it was sad. But I wouldn’t say that life was snatched away from them. Half of my friends died of AIDS in the eighties. More than half, really. My brother sadly died of a brain tumor. So I’ve been through it. And you’ll have worse happen to you, I just want to tell you.”

Worse? No. My idol was mistaken. There was no worse coming. The point was that I was living through the worst of it now. There had to be better times ahead. I had earned that. Maybe John didn’t understand that he was supposed to tell me what I wanted to hear. Was he just like everyone else in my life?

I softly switched strategies. “I feel like I know your point of view so well. But I’m curious about your relationship to yourself insofar as you feel comfortable sharing . . .”

John stared. “Sharing what?”

In truth, I wanted his soul laid out before me. But instead I asked for something that sounded more normal. “I’m curious about the journey of your life. How you experience—”

“Journey. I never say that.” It was a dig. But he is allowed to make digs. He is good at them. It’s an honor to be dug into by him. I tried a new word.

“The shape of your life?” But he was still thinking about my bad word.

“Whenever I have an actor that says the word journey, they don’t get the part in the end. Or humbled.” I was quick to assure him that I don’t use the word humbled.

“Rigorous is another word. Or surreal.” Fuck. I say surreal a lot.

I was beginning to realize that he may not want to be forced down a road of feelings. I thought we had counted down together at the edge of the pool but evidently only I had jumped in. This was not going to be Tuesdays with Morrie. Two gay men would never be so willing to meet in the middle like the two straight guys from that book were so happy to do. Morrie could have been bi, though. I remember him liking a good time.

I wasn’t sure what exactly I wanted from the man who I had long ago appointed my god, but I knew that I was in search of a feeling. I’ve learned in my pursuit of self-actualization that there is a weird paradox with mental health. On the one hand, the only way to transcend your issues is to accept them, but on the other hand, the only way to accept your issues is to know them. You spend years trying to identify the entirety of all your blocks and hang-ups and patterns, and their many origins. It’s endless work. And on the third hand, if you’re someone who lives in the brain, you face the inability to ever experience epiphany. Epiphanies, they say, occur when new insight meets a wave of emotion, but all of my own self-discoveries feel at a dispassionate distance. So here I am, in an endless loop of dissection and inspection, unable to ever attain peace.

All the pain, all the thinking, all the lack of self-compassion, had made me phobic of the possibility that I’d lost touch with my instincts—and at the end of the day, my instincts are all that I have. I wanted to know if John had ever felt this way. I thought to disguise a conversation about feelings as a conversation about instincts. I could get him there through the back door.

“My instincts have always been about humor,” he began. “The first thing I wanted to do was make myself laugh, and then my friends. We had a sense of humor that we obviously developed together, and I still have that. That’s the main thing. That’s what I’m trying to do when people see my movies: make them laugh. That’s how you get people to listen to you, and how you get people to change their minds. And that’s how you get them to keep coming back for more.”

Interesting. Maybe I’d lost my sense of play. When I look at photographs of myself as a kid, my eyes were so alive. I was shining. Do I still shine? Are the only people who shine as adults mentally unstable narcissists clutching awards? Should I try to be more or less mentally stable? John shines. Is he insane?

I wasn’t sure what exactly I wanted from the man who I had long ago appointed my god, but I knew that I was in search of a feeling.

“And you gotta make fun of yourself.”

My heart sank. Making fun of myself is something that I’m very good at pretending to do well. But it still hurts. I’m good at acting silly, and I’m good at playing a character of myself. But I spend so much energy trying to prove that I deserve to be on this planet that I never feel powerful enough to portray myself as powerless. I had never realized before that John makes fun of himself. He went on, “I always use my self-image humorously. The Prince of Puke . . . all those things that people called me, they were said nicely. Nobody gave me those titles because they didn’t like me. When William S. Burroughs called me the Pope of Trash, that was high praise. I went with all of it.”

I wanted to understand how John had allowed himself to wear his own persona so loosely, while I was still triple-timing that I’m an adult man who people should believe in. I asked, “But did you ever feel like you were wrestling to prove something?”

I could feel him enjoying the question. There might finally be flow between us. “If I was, I wasn’t conscious of it. I didn’t ever really think about it. I was just trying to make the next thing that would make me laugh.”

Why was someone I wanted to be just like so different from myself? Where was his sense of self-torture? Where was his fear of scarcity? Where was his damage? I needed to get it out of him. I needed him to be like me.

“I have this feeling that there’s a lot that I need to do in my life.”

“Well, you’re only thirty-five. You’ve got plenty of time.”

“Did you ever feel this way?”

He laughed. “Oh, people say, why aren’t you slowing down? You’re seventy-six. Because I believe you get one life, and this is it. And I’m trying to get as much out of it as I can. I don’t have to work right now. I have enough money, basically. So why do I drive myself so hard? It’s a good question. All people in our business are basically very insecure, and they’re trying to make up for something that they didn’t get when they were young. And they never will. But they want the world— strangers—to tell ’em how good they are. That’s insecurity.”

I am insecure. But I knew that. It was a relief to be told that he was, too, even though he seemed more secure than I could ever be. Was that simply the wis- dom of age? Or was it a symptom of having proved himself to the world more than I had? However he got there, I wanted it, and I wanted it now. “But now, on this side of your life, you’ve done so much, so I feel like people know you,” I said.

He nodded, “They do.”

“Has that put any of your insecurity to rest? Or has it changed your relationship with yourself?”

He mulled this over. “I think I’m reasonably content. But that sounds crazy, because I still battle with my emotions. Everybody does. It doesn’t necessarily get easier as you get older. New emotions appear. You start to think, well how much longer? I can’t say I’m middle aged. I’m not gonna live to be one-hundred and fifty-four.”

John was undoubtedly part of a different generation. I was just under half his age. In a way, it was hard to remember this, because he is one of the few people on this planet who has aged the right way: He believes that provocation is virtuous; he gives the benefit of the doubt to the underdog and to the kids coming up. He never became bitter or close-minded, as so many people tend to do as they grow older. I want to do it his way.

He smiled. “So things are good. Pink Flamingos is being preserved by the National Film Registry. I’m going to get a star on Hollywood Boulevard. The Academy of Motion Pictures is doing something with me. That’s all great. I think it’s all lovely.”

The man sitting before me was neither bothered nor unbothered by the overwhelming and ceaseless nature of life itself. Maybe it was generational. For as much flack as my generation receives for whining and moaning, you have to hand it to us—we picked up tools that no one gave us. We needed to figure out how to talk about our own feelings as soon as possible. And just as we were begrudged for overindulging those tools, we begrudge the generations before us for resisting self-inspection.

John is timeless, though. And the ease with which he lives may have more to do with an innate grace than an unwillingness to see himself. He lives in a headspace that feels good to live in. What a concept.

I sat there, uncertain what should come next. Our conversation had taken turns because I had spent the hour skirting around one simple question. I was scared to hear it come out of my own mouth, because I knew I would sound ridiculous.

I floundered. He watched me. Then finally, I allowed it to happen.

“Do you think I’m going to be OK?”

John asked it right back, “Do you think you’re going to be OK?”

No. It wasn’t mine to answer: “Do YOU think I’m going to be OK?”

He took a paternal breath. He would give me what I’d come for. “I do think you’re gonna be OK. But don’t panic and don’t put too much pressure on yourself about whether the next thing has to top Search Party, or be like it. Just keep going.

You have to keep going and things will change. There’s always another chapter. Life ain’t fair. I was born with a good hand with my family. And that is all it is. If your parents made you feel safe in any way, that’s how you’ll survive. If you didn’t, you’ll be fucked up your entire life. But don’t blame them after you’re twenty. I’ve always said that. Afteryou’re thirty, please stop whining.”

Oh my God. I’m thirty-five. My eyes widened. “But I just started getting good at it.”

It was true. I had spent the last five years of my life employing a team of therapists, energy healers, acupuncturists, self-help experts, and LA people to validate the pain I had spent the first thirty years of my life denying. Somewhere, early on in my journey (a word that I ultimately choose to keep employing), I felt victimized by aspects of my upbringing, as I imagine most queer people—and maybe all people—do. But my present isn’t my past. I have so much to be grateful for in the life that I’ve created for myself, but I’m still somehow addicted to despair, even when most of me doesn’t want to be that way. I suppose that when life stops hurting you, you start hurting yourself, just to stay in the game. It’s hard to see. But it’s what we do.

The pencil mustache crinkled under a half-smile. He liked what he was saying. “This is the hand that you were dealt. So shut up after you’re thirty.”

Should I have felt hurt by this? I wondered if he would have felt hurt if his hero had ever told him to shut up. I wondered if he would forever resist me after this meeting. I wondered what he thought of me, if anything at all. I wondered if I was ever going to arrive at this abstract feeling that I was so tired of scouring the earth for.

But none of that mattered. What mattered was that my hero had just told me to shut up. And maybe this is the key to how I finally become him so that I can finally become myself. It’s worth a shot, given it’s the one thing I’ve never even considered trying. It’s a note that might even be worth passing along to an entire generation of people fighting a cacophonous and omnidirectional battle to have our pain validated at any cost. And ultimately, if we try it and in the end it doesn’t work, what’s to lose? We have a lot of life left. A lot of it will be great; some of it may be worse.

So, here I go. I’m shutting up now.

This story was originally published in for A Great Gay Book, 2024 (ABRAMS)