In 2018, writer Tucker Shaw overheard a young man on his way home from work talking about the AIDS crisis. The young guy proposed how that era “galvanized the gay community” and “had spurred change”. He added that it had “paved the way to make things better, in the long run”. It’s a moment that stuck with Tucker, and he published his thoughts in a Twitter thread which quickly amassed more than 21,700 retweets and nearly 80,000 likes.

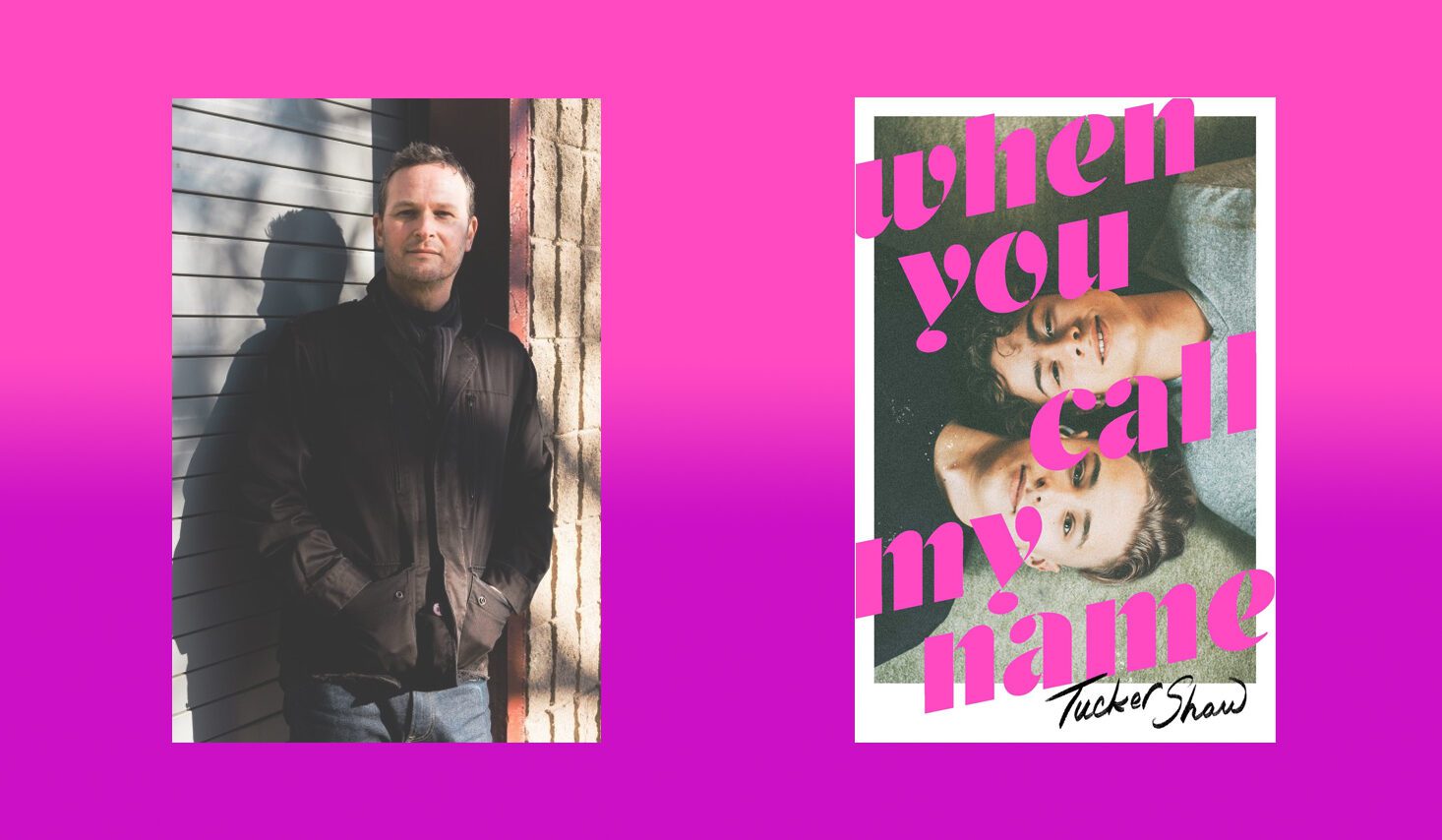

The thread resonated with people; both those who lived through that time and those who didn’t. It also inspired Tucker to write his debut novel. When You Call My Name is a poignant and uplifting blend of fact and fiction set in New York City at the start of the AIDS crisis. The story follows two teen characters, Ben and Adam, who are both coming of age during this turbulent time. The novel explores the tenacity and strength of queer friendship during the toughest of times, while paying homage to a city that faced significant loss.

Ahead of its release in the UK on 2 June, we caught up with Tucker to talk about why this story is important for a new generation of LGBTQ+ youth, how it can be a resource for those living with HIV today, and how he felt revisiting those memories from that time.

I’m going to start off with a question that may be quite loaded: why was this story important for you to write?

From a personal perspective, I think writing this story helped me to synthesize some of the memories that I carry from that time. I’m not unique in having a lot of complicated memories from those days, but I think that over the last twenty or thirty years, in many ways I’ve been a little bit hesitant to spend too much time in those old memories; almost trying to outrun them in a way, move into the future, and put the hard stuff behind me.

For young readers especially, I think people are curious. Not just in terms of facts and figures and this many people got sick or died, but really how it felt. I think that this book was my attempt to convey the emotion of a really small sliver of this very big story. I just wanted to give people a little window, because that’s how I think about history and that’s how I connect with history… is less about a military campaign or the dates in which a monarch reigned, but really understanding what life felt like; that’s my tether.

The story is set in New York – tell me about your relationship with the city.

Sometimes I think that it has much to do with the fact that nobody has a car, everybody’s on foot, so you actually have to interact with people all the time. It’s sort of like my best friend in a way, and you know sometimes when you have a best friend you can kind of take a little break from each other… Maybe that’s where I am now.

The novel starts off as an unassuming love story before developing into the AIDS epidemic – what is your connection to this, and why was telling this story close to your heart?

A lot of times when people talk about those days, especially within the gay community we talk about how dark they were or how sorrowful or fraught with pain they were. We still connected with each other, we still went out dancing, consumed music like fanatics, we still cared about fashion… we still fell in love. I wanted to make sure that somewhere in the record was a remembrance of that. Even under that cloud, we still found a way to… put our hearts out there, you know?

Did you envision it as a piece of historic culture when writing?

It is historical, in a way. As much as I’m amazed to believe, it’s been more than thirty years since that time. I wanted to create context and throw in pop culture and references to music and celebrities and things that were going on during the same time. I didn’t want to make a historical text; I wanted the characters, even though they perhaps use different slang or dress differently than other people, I wanted them to be recognisable and have people who you might meet today, except that you would have met them thirty years ago.

As someone living with HIV, the stories told are an eye-opening insight into an entire generation’s struggle with something so close to me. How do you see this as a resource for people who are living with HIV/AIDS in today?

What I would love readers to take, LGBTQ+ readers especially but anyone, is the capacity that we have as a community to really care for each other. I think at that time and still even now, it always astonishes me to see how strong the stigma is. I didn’t want to write a story where I wallowed in the misery of it all; but I also didn’t want to pull any punches on that front. I wanted to be maybe a little bit grittier, to be realistic.

But ultimately I want people to come away with a belief, especially within themselves, especially young LGBTQ+ people, but for all readers to see within that book and maybe appreciate all the potential they have in themselves.

With the incredible medical advances in the field of HIV/AIDS, the reality of being diagnosed today is a world away from the setting of the book; how do you envision your characters today, in an ideal world?

Honestly it’s almost harder for me to imagine them in a world with the internet, and cellphones. There’s a lot of scenes in the book that hinge on trying to find each other or not knowing where someone is, or missing a telephone call… these things that don’t really exist anymore. When I was growing up in the 70s and 80s there was no representation at all in TV and movies and if there was it was always very stereotypically negative, or tragic.

Being a teenager during that stretch was like, ‘Is this what it’s going to be for me?’

One thing that always drives me crazy is when people say ‘HIV/AIDS killed an entire generation’; it’s like, no it didn’t. It killed a lot and it devastated a lot of people but there are still people around today who lived through it and to suggest that they’re not here is to suggest that they’re worth forgetting, and I don’t think that’s true at all.

Were you surprised by things you found in the writing process?

There were a lot of ghosts that I interacted with, but what I’ve learnt is that ghosts don’t always haunt you in a bad way. Sometimes they stay with you in a beautiful way and can guide you, and give you a sense of peace and optimism. I hadn’t expected that. It was really gratifying, in a way. To be able to not turn away from some of the sorrow, to be able to go back and look at it. You can’t have darkness without light, so to be able to see in that some beauty and inspiration, and hope…

It’s June, the start of Pride Month 2022. The UK release of When You Call My Name comes at a poetic time, and will no doubt serve as a source of inspiration for a generation of young people discovering themselves. How does this make you feel?

I’m really aware that this book reflects a tiny corner and set of characters in New York City, and that the stories of HIV/AIDS and the world are so much bigger than that. If the book unlocks opportunities for other people to write about these things or similar things, that will be a success for me.

I believe one of the great results of telling stories is the inspiration for other people to tell theirs, and I would love to learn so much more from other people around it. My heroes are the people that I connected with while I was young – it’s my friends. Having that base of support and understanding and belief in each other really gave me some balance and grounding to be able to reach, take chances, and know that I always had a place to fall.