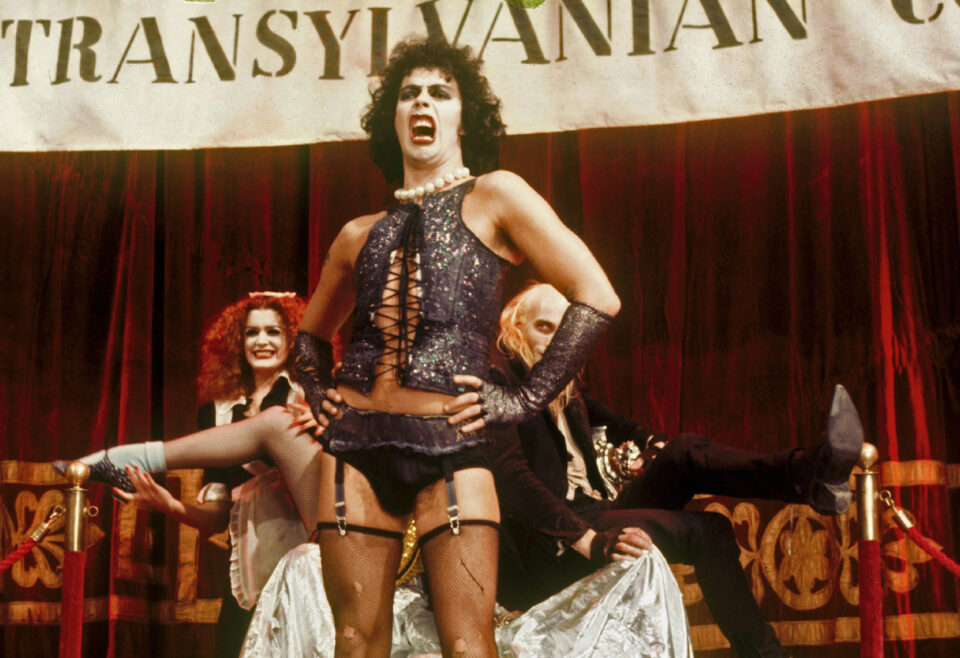

Twice I have shown The Rocky Horror Picture Show to men and they’ve been reduced to tears. The soft wiping of eyes usually starts when Tim Curry sings ‘Don’t Dream It, Be It’. I cried the first time I saw it, too.

I first watched Rocky Horror on the day after Halloween, feeling a bit fragile from the night before. As soon as the credits began to roll, I went back to the beginning and started it again. The film has such a raw emotional and visual power that even those of us born 20 years or more after it was released are often shocked by how radical it is.

Every Halloween, the Rocky Horror discourse sets in. I feel increasingly forced to defend my love of this film from a battle of opinion pieces. Go to any Rocky related comment section this time of year and you’ll see the same debates about the ethics of Frank-N-Furter’s choices. Some of the points are valid, and some pretty exasperating.

What I think is important to recognise is that The Rocky Horror Picture Show is just another text in the history of queer gothic horror. Homoeroticism, if not explicit queerness, has always been strongly linked to gothic horror as a literary genre. One of the first English-language vampire novels was Carmilla by Sheridan La Fanu in 1891, which first invented the lesbian vampire archetype.

Vampires kill and eat people, but often they also hypnotise, seduce or coerce humans – exactly like Frank-N-Furter. Queerness and horror have been historically linked by heterosexual and cisgender writers in order to demonise us and reinforce the fear and disgust of a cis-het audience.

But Rocky, on the other hand, truly is by and for queer people. It is an exploration of queer horror through a queer lens.

Bad people (or vampires… or aliens from the planet Transexual) are more compelling than good people. We are allowed to love Frank-N-Furter as a villain without loving his behaviour; nobody who adores Frank-N-Furter would defend his actions if they were a real documentary of events.

The majority of my frustration stems from how we’ve felt the need to defend the morality of Frank in a way that heterosexual media never has to defend itself. I challenge any dad to defend every action Liam Neeson makes in the film Taken.

We love Frank-N-Furter in large part due to Tim Curry’s stunningly detailed performance. His ability to switch from erratic madness to tentative vulnerability carries the (at times nonsense) plot with the skill of a true artist. When the bravado and the power and the sex appeal all crumbles away, and Curry sits broken on the steps singing ‘I’m Going Home’, you can’t help but think about a scene just the same playing out outside gay bars everywhere every Saturday night. The sadness and pain beneath the larger than life exterior is a duality a lot of LGBTQIA+ people know all too well. A lot of us have felt that “everywhere it’s been the same, like I’m outside in the rain”.

As someone who grew up with their first exposure to queer representation being Glee (we do *not* talk about the Rocky Horror episode), I grew up on highly self-conscious LGBTQIA+ representation which aimed to paint queer people as innocent victims, every story designed to make us cry and pity the disempowered queer characters. This was media made for the heterosexual and cisgender gaze, appearing to have been made with a mindset of “if they can only pity us enough they will agree we deserve rights”.

But what shocked me about Rocky Horror, and what made it feel so revolutionary, was its complete refusal to be palatable to the cisgender, heterosexual gaze.

Rocky Horror is unapologetically freaky and it doesn’t explain itself. What is the planet Transsexual in the galaxy of Transylvania? We don’t know, we don’t belong there so it’s none of our business. What sad backstory did Frank go through to become the way he is? Who cares, look at what he’s like right now!

As a young person who was overexposed to media which made me feel like being queer was something inherently sad and difficult, seeing it presented on screen as something entirely different – chaotic and radical – was so deeply refreshing. I’m not saying that to live in Frank-N-Furter’s Castle is some kind of utopia, but, “it’s not easy having a good time”!

Our enjoyment of media does not have to correlate with how well it portrays our individual experience. We don’t need to grade the value of queer art on how well it explains itself to a straight, cisgender, or even anti-LGBTQIA+ audience. We are allowed to have multitude and complex feelings about a piece of queer art, and still have deep love for it.

One of the most incredible features of The Rocky Horror Picture Show is its enduring appeal. Something that has the power to make us cry almost 40 years after it was made has a resonance that we should never doubt. We also have to be mindful to respect those queer elders who found their first and maybe only queer spaces of their youth in cinemas and theatres watching Rocky. Most of them did not have the luxury we have of being able to go to gay bars or queer events, or seek queer community online.

Rocky Horror was a lifeline for many of our queer elders and I hope that fact can give us pause before we tear it down or disrespect its contributions to queer cinema. That doesn’t mean it is above critique, but we should tread carefully. And honestly, queer people need to hear now more than ever: “Don’t dream it, be it.”

Amy is an ambassador for Just Like Us, the LGBT+ young people’s charity. Just Like Us needs LGBT+ ambassadors aged 18-25 to speak in schools – sign up now.