Millions of pounds are being spent in the USA and Europe to find a cure for a killer disease – AIDS. Only very few of us will contract this rare illness and there is no doubt that a cure will be found. In this article we highlight the work of the Terrence Higgins Trust, the AIDS charity, through the graphic case of someone suffering from AIDS.

Have you ever wondered what you would do if you were diagnosed as having AIDS? Go into a severe depression, maybe commit suicide? Or even arrange a week of non-stop sex?

Whatever you do, you are most likely to go through three distinct phases – disbelief, anger, resentment and pity; and then, maybe, acceptance. You have probably heard of the Terrence Higgins Trust, the AIDS charity, but how would they help you? And why do they need your money?

Having any serious illness is worrying. Worries about who would look after you when you are not in hospital. About who would cope with your depressions and your moods. Would anyone? What if your lover or friends walked out and did not want to know? Luckily, for most of us, we will not have to face such problems. But, for those who do, and there are now 69 confirmed cases of AIDS in the UK, questions like these can mean the difference between a positive, maybe even happy few months/years or a deeply depressing and worrying time waiting for death. Incidentally, 32 people with AIDS have died in Britain. Let us imagine the worst case and see how the Trust could help you. Let’s do this through a story – but a story based on real experiences which the Trust has faced in the last few months.

John called the Trust’s helpline last January. He had been living with his lover, Philip, for a couple of years and they had just bought a flat together in the Balham area of London. They had a relatively monogamous relationship; that is Philip was monogamous and John had relatively little sex elsewhere. This was not John’s first call to the Trust. He first phoned in October after reading an article on AIDS in HIM/GAY TIMES. He was feeling tired and run down. He had been reassured by the person on the helpline then, but just to be sure he had been advised to go for a check-up at his local clinic. Well, there hadn’t been time and it took so long anyway. And wasn’t he tired this time last year? Probably needed a holiday, John thought.

Questions

In January, Philip noticed a purple bluish mark on John’s leg. He’d also observed that John had been losing weight. He was sure that John had been consciously ignoring these symptoms and pressed him to phone the Trust again. They argued. John phoned.

The Trust seemed a little more insistent this time that John should go for a check-up. Yes, they agreed, it was a very rare disease. No, they wouldn’t say he definitley hadn’t got AIDS. And yes, they would send some leaflets and even a poster if he wanted.

At the clinic there was the usual queue of attractive men. John’s name was called. The doctor asked all the standard questions and wanted to do a biopsy on the mark on his leg. Yes, it might be AIDS. Could he return tomorrow for the results and maybe more tests? It was Philip who contacted the Trust’s helpline this time, though often the Trust hears from the social worker at the hospital. There were so many questions which Philip wanted answered. Would John’s tests hurt? If it was AIDS would he ever come out of the hospital again? Should they have sex together? Did he have AIDS too? What should John say at work – should he tell them? Or his friends? Or people he’d slept with. The Trust offered all sorts of help: from the helpline – Mondays to Fridays, 8pm to 10pm – to a buddy to visit John regularly. The Trust also provides a support group for people with AIDS and their close friends and care partners.

Support Group

They also answered Philip’s questions. The tests didn’t hurt. Yes John was likely to come out of hospital, possibly in a couple of days. Yes since they’d been having sex before, if he was likely to catch something he’d probably have caught it by now. It was unlikely that he had AIDS but he should go for a check up too. It was up to John if he wanted to tell people at his work, his friends or even people he’d slept with. John spent three days in hospital undergoing tests. It was AIDS. And Philip also had a check-up; they found no symptoms or signs.

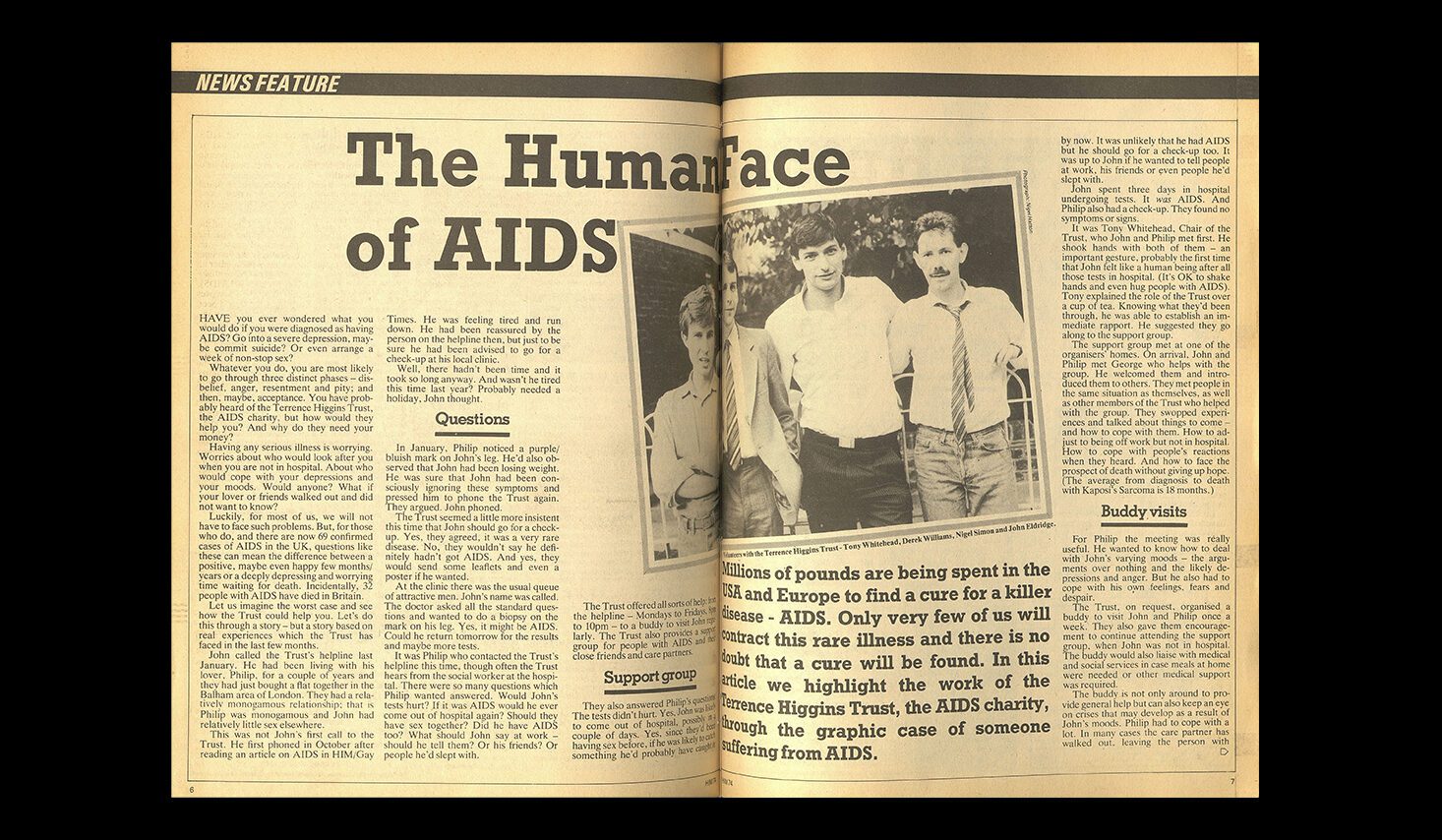

It was Tony Whitehead, Chair of the Trust, who John and Philip met first. He shook hands with both of them – an important gesture, probably the first time John felt like a human being after all those tests in hospital. (It’s OK to shake hands and even hug people with AIDS). Tony explained the role of the Trust over a cup of tea. Knowing what they’d been through, he was able to establish an immediate rapport. He suggested they go along to the support group. The support group met at one of the organisers’ homes. On arrival John and Philip met George who helps with the group. He welcomed them and introduced them to others. They met people in the same situation as themselves, as well as other members of the Trust who helped with the group. They swapped experiences and talked about things to come – and how to cope with them. How to adjust to being off work but not in hospital. How to cope with people’s reactions when they heard. And how to face the prospect of death without giving up hope. (The average from diagnosis to death with Kaposi Sarcoma is 18 months.)

Buddy Visits

For Philip the meeting was really useful. He wanted to know how to deal with John’s varying moods – the arguments over nothing and the likely depressions and anger. But he also had to cope with his own feelings, fears and despair.

The Trust on request organised a buddy to visit John and Philip once a week. They also gave them encouragement to continue attending the support group, when John was not in hospital. The buddy would also liaise with medical and social services in case meals at home were needed or other medical support was required. The buddy is not only around to provide general help but can also keep an eye on crises that may develop as a result of John’s moods. Philip had to cope with a lot in many cases the care partner has walked out, leaving the person with AIDS all alone. The buddy also gave Philip a break – some time to himself to relax.

The few months after diagnosis were fairly happy. John did return to work but didn’t tell people what was wrong with him. He did tell people he’s slept with. Which led to more calls to the Trust and further requests for leaflets. John had his ups and downs and Philip and he had their fights. But Philip stayed with him. It was Philip who prompted John to get help with the support group and together they helped with other Trust activities, such as speaking to groups and helping with fund-raising. Not only did this help other people but it also gave them courage to face up to the reality of their own situation.

Whilst he had a balanced perspective on his own conditions, nothing infuriated John more during those months than the unbalanced way the media treated his disease. Shock horror headlines were common. ‘Gay Plague Hits Gran’; ‘Alarm As Lethal Plague Hits Non-Homosexuals’; ‘Thousands of British Gays Have Symptoms of AIDS’. Although the Trust sent out information to the media, the opportunity to create an attention-grabbing headline was too inviting for many papers.

Helpline

John went into hospital three times during the year following diagnosis. He had various different illnesses. In AIDS the body’s ability to fight off disease is weakened – the immune system is deficient of antibodies to fight off illness. An infection which could normally be dealt with routinely by the body becomes a major hurdle. Philip visited John, as did many, though not all of John’s friends. The Trust also provided a major source of help and support.

The third visit to the hospital was John’s last, he never recovered.

AIDS is diagnosed when one or more characteristic and serious infections develop without any known cause. They include PCP, a lung infection; KS, which is similar to skin cancer; and other unusual cancers and infections. People with AIDS have often suffered a period of ill health prior to diagnosis such as profound fatigue and drenching night sweats. These symptoms are not unique to AIDS, occurring commonly in other diseases such as flu, and are not therefore used for diagnosis. If you are worried about your health and the risk of developing AIDS, talk it over with the volunteers of the Trust’s helpline. They are gay themselves and understand your fears. They are well informed and will help you to make sense of the facts and fallacies surrounding the disease. The helpline is open Mondays to Fridays from 8pm to 10pm.

This article was prepared exclusively for HIM/GAY TIMES by members of the Terrence Higgins Trust.

For LGBT History Month 2022, we are publishing four historic GAY TIMES Magazine features from our archives and making it available on our digital channels for the first time ever.

It follows the groundbreaking campaign from SKITTLES®, GAY TIMES, Switchboard and Queer Britain last summer – titled Recolour The Rainbow – which breathed new life into archive imagery from Pride’s past to acknowledge and celebrate those who have come before us in the fight for LGBTQ+ liberation.