Throughout history, queer people have been at their best when they come together to form collectives: communities that draw strength from both their diversity and unity in order to push our agenda forward.

UK Black Pride began in 2005 with a minibus trip to the seaside, organised by lesbian and bisexual women of colour. From its humble beginnings, UKBP has grown exponentially – attracting LGBTQ people of colour from around the country to unite and celebrate at the intersection of their identities.

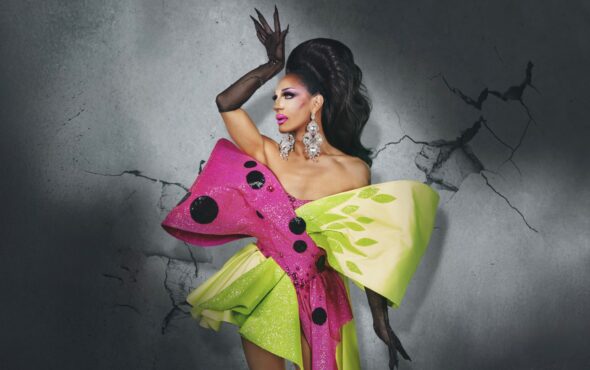

This year, Gay Times is proud to support UKBP as their official media partner. In celebration of this announcement, Lady Phyll, co-founder of UKBP (the ‘co’ stands for community), graces our cover for the first time.

We’re partnering with UKBP to raise awareness about the incredible work they do, and the importance of events and organisations such as theirs. We’re constantly learning how to be better allies to everyone across the far reaches of the colourful spectrum that is the queer community, and UKBP as a collective continue to educate and inform us how best to step up to the plate as a truly representative and inclusive company.

Lady Phyll and the entire team at UK Black Pride are demonstrating the power of loud, unapologetic unity in the face of hatred and bigotry – often unfortunately from sectors of the LGBTQ initialism.

In our interview with Phyll, conducted by Otamere Guobadia, she explains why UK Black Pride is so important to the community and how white people people can be better allies to our queer siblings of colour.

“Until we all have the same rights, until we all do not face any form of injustice, until we all have proper access to housing, to health, to school, to education, then there will always be a need for Black Pride. In an ideal world, we wouldn’t need [any Prides] would we? We wouldn’t have to deal with championing or fighting for rights, for LGBTQ people, but we don’t live in an ideal world because there’s homophobia, biphobia, transphobia, but there’s also racism. Black Pride was set up [not only to celebrate POC], and have pride of place, but to also combat systemic racism.”

There’s a stark difference between tolerance and acceptance; between empathy and compassion; between opposition and allyship. The average life expectancy of a trans woman of colour in the United States is just 35. One would think that it would be impossible to see figures like this and still actively oppose the voices in the community who are identifying these issues and forming action plans to directly combat them. And yet, the regrettable truth is that often the opposition to these voices come from our queer siblings.

These are the same people who ask for a ‘white history month’, a white stripe on the Pride flag. To these people, we implore you to become aware of your privilege, the rose tinted lens that your race places upon your vision, and draw upon your own experience as part of a marginalised group to begin attempting to understand the battles that QPOC face – while accepting outright that you’ll never be able to truly empathise.

Related: Lady Phyll shares an open letter ahead of UK Black Pride 2018

“We’ve got young queer black and brown bodies who are living on streets, who have no place to go, who don’t know where their next meal is gonna come from, who have been [cast] out by their families, and need a place to feel like they’re loved, need a place to shed a tear and to know that there are people out there with a shared commonality… of course if people want to put black and brown [stripes in the flag] because that’s how they identify with it a lot stronger, then why should anyone question that? [And] those arguing that we’re ruining the flag, I would say that they’re ruining society by not letting people be.”

Privilege is one of the hardest things to dissect – especially if you’re someone who possesses it. As LGBTQ people collectively, we can identify the advantages that our straight peers receive in life quite easily. Now think how the difference between us and heterosexual people is compounded by other factors like being a woman, transgender, asexual, disabled or BAME – all minority groups with a history of oppression outside of queerphobia.

Those of us in the community who don’t experience any of these intersections of marginalisation have a responsibility to our queer ancestors to leverage our privilege as a weapon to enact change. Our privilege isn’t up for debate: we were born with it just as some were born without it. The decision lies in how you choose to use it.

It’s vital, now more than ever, that we continue to facilitate these conversations and battle against the erasure of queer people of colour from the equation. We’ve said it before, and we’ll say it again: the modern LGBTQ rights movement was started by a trans woman of colour. We owe so much of our freedom, history and language (see: ‘yass’, ‘gagging’, ‘work’, ‘kiki’ and basically anything you yell while watching Drag Race) to the beautiful queer people of colour who’ve been fighting fires from multiple sides from birth, and now it’s our turn to support them as they have us for so long.

In parting, Phyll shares her shimmering visions of utopia:

“I want it to feel and look safe, beautiful, shades of the diaspora — where our beings of being black and queer. I want us to be ‘busy being black’ but in such a beautiful way that we’re not tired. I want to be able to look down from Heaven, or wherever the afterlife is — if there is one — to know that young people especially don’t have to struggle. I want to know that our [black] queer selves can walk into the boardroom and not be mistaken for the tea lady. I want for us to be walking down the street with a hijab on without feeling that someone from behind is going to drag it off. I want for acceptance, not tolerance. I want for understanding, love, peace and harmony. I want for all forms of discrimination and racism to be eliminated.”

Buy your copy of Gay Times to read our full interview with Lady Phyll.