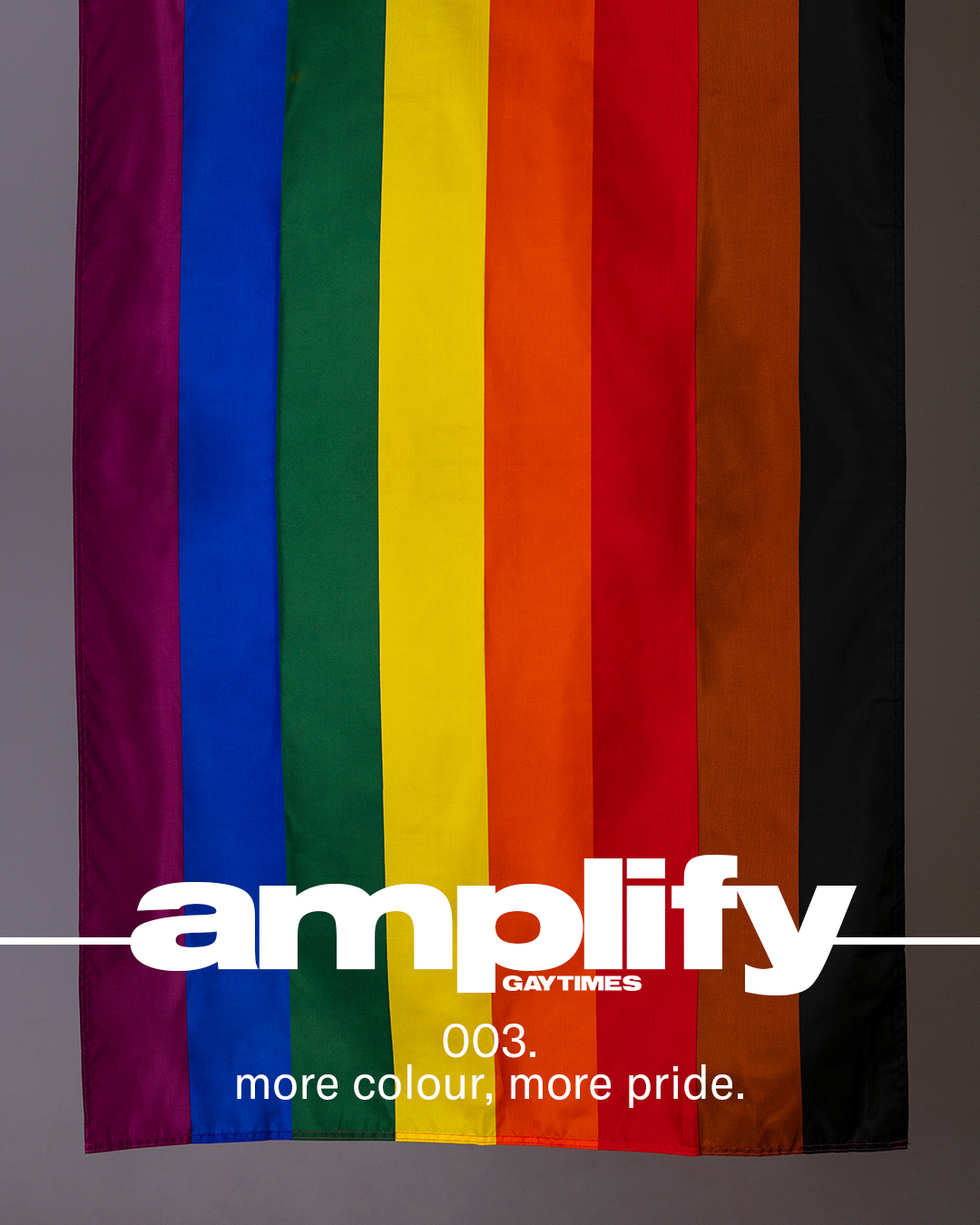

“This eight-stripe flag is not a replacement for the six-stripe flag. It is a way to symbolise, to highlight, and to stand in solidarity with these other identities.”

When the Executive Director of the Mayor’s Office for LGBT Affairs in Philadelphia, Amber Hikes, and her team unveiled a new eight-stripe rainbow flag for Pride Month back in 2017 it was with the aim of giving a new symbol to the community that better recognised LGBTQ people of colour and their experiences.

Within 24 hours, however, a media storm had been whipped up around this more inclusive design, with certain parts of the community rejecting the flag and claiming that black activists had “hijacked” this symbol of Pride.

It quickly brought to the surface the often-ignored issue of racism within the LGBTQ community, which had long been lurking underneath not getting the appropriate conversation and action needed to tackle discrimination within our global queer family.

More recently in the UK, Manchester Pride announced plans to official adopt the eight-stripe flag as part of their celebrations this year, in solidarity with LGBTQ people of colour.

Once again, the negative social commentary around their decision within the community revealed a lack of understanding of what the More Colour, More Pride flag actually stands for, but also some blatant racism.

To give more context to the conversation that currently surrounds the More Colour, More Pride flag, Chloë Davies, a volunteer at UK Black Pride and queer woman of colour doing her bit to help change the world, speaks with Amber about the creation of the symbol, the backlash against it, and how this could be an opportunity for the community to come together in the fight for true equality for all.

Chloë: What inspired you two and half years ago to unveil the More Colour, More Pride flag?

Amber: We introduced the flag to the residents of Philadelphia and accidentally to the country, and then the rest of the world, in June of 2017. We actually worked with an ad agency to develop a symbol that really spoke to the experiences of LGBTQ people of colour, that are distinctly different to those of white LGBTQ people. There were a series of incidents over the last 30 years that contributed to the conversation here in Philadelphia. We saw a report from 1986 –given to the mayor at that time – that documented discriminatory practices in bars and organisations, things that are not unique to Philadelphia and that you see all over the country and all over the world. More specifically, we saw discriminatory dress code policies, black and brown people being required to show different forms of identification to get into a space where white folks could just come and go. We also saw a lack of representation in the leadership of our organisations. But what was really the smoking gun of this issue was an owner of a gay bar in Philadelphia caught on tape saying the n-word over and over again, and laughing about it. That was very painful for a lot of members of the community. It led to boycotts, protests, calls for leadership changes, along with a series of town halls addressing the experience of racism in the Philadelphia LGBTQ community. So when I came on as the Executive Director of the Mayor’s Office for LGBT Affairs in Philadelphia, I was clear that I wanted to address those issues both symbolically and substantively. Substantively, we wanted to push legislation, host community conversations, and change policy. But symbolically we needed something that could document this time in our country’s history, this time in our city’s history, the conversations we are having, and really to make a promise to LGBTQ people of colour, specifically, to say that these concerns are not going to be ignored anymore. They’re not going to be dismissed. We’re going to acknowledge them, and do so head-on. That’s how the flag came to be.

Amber Hikes and Chloë Davies

Chloë: So you introduce the flag and what happens?

Amber: We raised it in Pride Month on a Thursday. There were unicorns, glitter, and the usual queer excitement. In Philadelphia, people understood the context. They knew the conversation we’d been having over three decades. They knew the recent events and the unrest that existed in the city at the time. Unbeknownst to us, this flag went viral within 24 hours. We raised it on a Thursday and CNN reported on it first thing Friday morning. It was viral immediately. So what happened was this conversation started taking place around the country and world without the local context. So when LA and San Francisco receive it, or London and Sydney got it, the narrative changed. They received this news as ‘These activists are changing the flag.’ It was presented without context, and most of the people telling this story had not experienced racism within the LGBTQ community. So once again we saw the voices of LGBTQ people of colour being shouted over, shouted down, and white-washed. The vast majority of folks were excited about the unveiling and the response was overwhelmingly positive, but of course that wasn’t the entirety of the response.

Chloë: So I’m going to come back to context because that is really relevant to where we are here in the UK. How did you change the context after it went viral? At least in terms for the US and Australia where they’ve suddenly seen this symbol that actually has underpinned for a lot of – unfortunately – sensitive white folk how they view their flag. How did you then change that context because we’re now two and half years later and it’s around the world.

Amber: Well the brilliant thing about how quickly the flag spread was that it forced a conversation that was clearly not happening in other places in the way that it was here in Philadelphia. Seeing that flag and that image, and then seeing the visceral response certain members of our community had, proved the point. People know that I received hate mail and death threats for these stripes on the flag. And as horrible and painful as that experience was personally, it proved the point over and over again. These individuals are shouting over us saying that racism doesn’t exist, saying that we are making up. But while you’re shouting over us, you’re calling me the n-word. You’re saying that black activists are hijacking the community, and that there is no place for us here. You’re proving the point over and over again. It actually helped us to begin having conversations that were long overdue about how experiences can be so different for members who are supposed to be from the same communities. It really prompted a much-needed conversation.

Chloë: You are now travelling around the world and you get the update from your office from someone who tells you, ‘Manchester Pride in the UK is adopting the flag. They’ve openly said we stand in solidarity of LGBTQ people of colour and for this reason we are adopting this flag.’ What was that like? Because this was the first city in the UK that turned around and said, ‘We get it. We understand it and we want to be a part of this conversation.’

Amber: I had two distinct responses. I was overwhelmed with joy. I was so excited and so happy for you all – specifically LGBTQ people of colour, but also white folks who want to do better, white folks who think they are great allies but really don’t know what is required to show up as true allies. So I was overwhelmed with joy for that decision. But I was also absolutely concerned about the response. It’s because I knew how much of a challenge it was – not just for me, but for LGBTQ people of colour as a whole – to see what bit of backlash can come from white people who are supposed to be our siblings in this fight. White folks who, when we were fighting for equal marriage or the end of the epidemic, we were on the front lines together. But I know how heartbreaking it is to see white LGBTQ folks say, ‘No, no, no, this isn’t about you. This space is not for you. You adding these stripes on this flag somehow takes away from our experience and we will not allow it.’ How heartbreaking it was as black and brown LGBTQ people to see that response and say, ‘Oh, we really are not there yet. This community is not ours. Even here we are second-class citizens.’ So I was worried about that, and I hoped that was not going to happen. Maybe Manchester was not going to have that experience. So I was simultaneously overjoyed and really concerned that that would be the reality.

Chloë: This is a monumental thing. It’s not just you – I recognise that this is a team effort in your office – but you’ve all done the work. Does it bother you when it’s reproduced? How do we authentically do that work with you?

Amber: Oh no! Not at all. In fact, when we put the flag out there, we put it out into the public domain. There’s no trademark on it, nobody has any rights to it, it is for public use, consumption, however folks want to use it. That was a very intentional decision. That’s exactly how Gilbert Baker did it with his original six-stripe rainbow flag, and all the iterations of that. We wanted to fall in line with that as well. There is a chance this flag will move on and not be connected to my team in the way the six-stripe flag will be connected with Gilbert Baker’s name, and that’s fine with me. I just want to make sure that people everywhere can see it, and finally see their experience reflected. We deserve that as a community. We have so many flags that represent so many different identities, so that’s why it was important for me to have that out there and for people of colour to be able to look at it and say, ‘Here we are too.’ The same way that we can say the rainbow flag is for the whole LGBTQ community, but we also know that bi folks have a separate flag, lesbians have a separate flag, trans folks have a separate flag, and intersex folks have a separate one, and that’s okay. The rainbow flag can be the catch-all, but we then have separate flags to represent different identities. That’s the beauty of the More Colour More Pride flag.

Chloë: For myself as I identify as an LGBTQ woman of colour, I always look to history. History is important to me. I come from an African-American background, and our history and where we come from is inspired in everything we do. Your family, your elders (Grandparents, Aunties and Uncles) from one generation to the next they pass down our stories. I never felt like, whilst I was part of a ‘rainbow family’, that it was completely whole until I saw this flag. And then suddenly I felt, ‘Hey, these are my colours, and then there are my colours, and it’s all together as one.’ That’s powerful. So how do we get that transition here because I guess what we’re struggling with in the UK is very much similar to Philadelphia. People of colour are saying – especially in the LGBTQ community – ‘We don’t see ourselves, we haven’t felt loved, we don’t feel visible, and we don’t feel safe, and in this way with this flag we are seen.’ And again, like you’ve seen in a lot of communities, a large majority of the white community are saying, ‘Hold on, we don’t even want to hear this part of your conversation.’ So how can we make the balance? What words can you give to us here in London to actually get the community behind us?

Amber: That’s so heartbreaking, but unfortunately it’s not surprising. What I will say is, that this was part of the conversation we had to have here in the city. Once folks understood the flag, they were grappling with, ‘How do I continue to be an ally? How do I continue to stand in solidarity?’ So what I would say to white folks specifically who feel like this flag isn’t necessary, and that the rainbow flag included all these voices beforehand is that 1) the six-stripe flag still exists in the same way it always has. When trans folks got a flag, the existence of that new flag didn’t take anything away from the six-stripe design. You can still raise that flag if it feels more comfortable for you. This eight-stripe flag is not a replacement, in the same way that that those other flags didn’t replace the original. Instead it is a way to symbolise, to highlight, and to stand in solidarity with these other identities. That is literally the purpose of any flag we have – to stand as a symbol for an identity, whether it’s a country, a municipality, a company, it stands as a symbol to recognise and highlight the experiences of this entity. The existence of this flag doesn’t take away from anybody else’s identity. It only adds to great inclusion. The other thing I’d say to folks who are really pushing back against it is, this is a perfect opportunity to stop and think about why. Why does this upset you? Did you have this same reaction with other flags? Because let’s make this clear, at any Pride parade there are many different versions of the rainbow flag. I’ve seen ones with a Mexican flag as part of it, the Star of David, ones with marijuana leaves, there’s all kinds of different rainbow flags to represent different communities and identities. If that did not offend you, but this one does, then why? You’ve heard me talking about interrogating your privilege and interrogating your surroundings, but I need folks to interrogate their responses. If your response to something that stands in solidarity with black and brown folks is to be viscerally angry, and that’s not your response to other symbols, I need you to think about why that is and what that says about you. That’s how we saw the conversation start changing. We also saw there were folks who live in their range who were like, ‘I can’t quite understand why, but I just don’t like it. I don’t think it’s pretty.’ Whatever that was.

Chloë: Or, ‘It makes me feel uncomfortable…’

Amber: Right! Then there were other folks who were absolutely livid about it, and frankly were just blatantly racist. What we saw with those people who were just a little bit uncomfortable, when they saw that the people who agreed with their discomfort were just blatantly racist, they were like, ‘Oh wait, no no no – I don’t want to be associated with that. I need to recognise what my discomfort is rooted in, and let me start to interrogate why I feel that way and figure it out.’ So that’s just a little bit of what I would give folks to consider for themselves. And I have to say, even if you don’t feel this is necessary and you don’t think there was any point to it, I need you to talk to LGBTQ people of colour, period. Have you asked them what their experiences are? And only then, when you shut up and listen, will you be able to move forward. This idea of white folks shouting over people and telling LGBTQ people of colour that their experiences aren’t real or valid, it does not feel dissimilar to when straight folks shout over queer people about the ‘gay agenda’.

Chloë: I just want to touch upon Jussie Smollett’s attack. We come from that place and we recognise it, but also the pushback from people that… this is an everyday reality if you’re an LGBTQ person of colour. Like actually to live and walk in the street. We’re not just talking about the Jussies, we’re also talking about our trans women of colour who are dying and nobody is caring. The majority isn’t hearing or recognising or remembering them. Where is the line where actually enough is going to be enough? The pushback is, ‘Well, what did he do that actually caused this to happen?’ Even when it happens, the narrative of ‘Well, there must be missing pieces of information.’ A gay black man can’t just walk the street and not have something happen to him that he hasn’t brought upon himself?

Amber: That kind of victim-blaming is just so painful to hear about – especially as a person who holds all of these identities. I identify as a black person, a queer person, a woman, so that kind of victim-blaming for a person who has all of these intersecting identities, it’s so painful. What I can say is, if your response to hearing about an experience of a hate crime, is ‘Well, what was he doing?’, that’s rooted in privilege. You don’t have access to the real lived experience of people in marginalised groups. Again, I’d say that if that’s your true position, it is rooted in privilege and good on you for not having to be terrified, to have the real experience of having your fellow citizens be out to harm you. That’s just not a reality for those of us from marginalised communities. I would push folks again to just have conversations with people of different identities.

Chloë: You’ve lined up my final question perfectly because I want to end with your amazing rallying call at Out & Equal when you said, ‘It is time to recognise our privilege.’ How do we tell the people in the UK how to weaponise their privilege for each other? What I think is inspiring, and I think people actually don’t really remember, when we’re in these positions that you and I are in, whilst we might be the many different layers of woman, unapologetically black, queer, or in my case a parent, we speak up on behalf of our entire community. We don’t just speak up for people of colour. We speak for our trans, non-binary, white, lesbian, accessible siblings, we speak for LGBTQIA+. How do we weaponise that privilege for all of us? Because if we don’t do it together, we’re never going to get anywhere.

Amber: When we’re talking about weaponising one’s privilege, the only issue with throwing that out to folks is there’s a whole process that comes before weaponising your privilege: you have to first recognise your privilege. That’s my concern with some of these folks who are having this push back. You have not yet recognised the privilege you have as a white LGBTQ person if you are pushing back against something as simple as two stripes on a flag. You don’t understand.

Chloë: You don’t want to get it.

Amber: You don’t want to get it! You certainly can’t weaponise privilege if you don’t even recognise that you have it. So that’s the first step. We all have privilege, right? Even as a black queer woman I have privilege.

Chloë: Me too.

Amber: So you need to find out what you can do with that privilege in service to folks who are marginalised in this conversation specifically. If we were talking about white folks people who also hold an LGBTQ identity, this is a perfect time to have a real conversation on first recognising the importance of the flag and what it means to other folks, but then use that opportunity to have a real conversation with other white people. Explain to them that they need to recognise their privilege and start listening to different experiences and different identities. To recognise your privilege and then weaponise it, you are calling in people who hold similar identities. Then at that point we can start to show up, speak up, and stand up for one another. We’re talking to people, we’re listening to them, we recognise what their needs are and we find ways to show up and to stand up. This labour is difficult – it’s exhausting. And particularly exhausting when you’re a member of multiple marginalised groups. We need allies, we need accomplices in this work because, as you mentioned, if we don’t do it together, it’s not going to get done. We’re all we’ve got.

Chloë: Thank you. I can’t say anything more than thank you. Everything I could have hoped for this conversation that my community can hear… when we find authentic people that amplify thousands upon thousands of voices using their platform and their privilege, we need to share that message. We need to talk about it, and we need to bring each other together. How do you think we got equal marriage in the first place? Everybody came together. So why, when we are having these types of conversation, is it any different? I said this at a panel event last year when someone said, ‘We have equal marriage now, so the battle is won – what’s next?’ I turned around and I said, ‘Y’know what? I don’t know what that’s like, it doesn’t exist for me. But what I do know is, when I go out and do what I do, I volunteer my time for our community, time I take away from my two young children and I never stop fighting for you. So the fact you’ve already given up on me is incredibly disappointing.’ We can’t keep doing that to each other. Because who else have we got apart from each other? We have a lot of work to do but I believe we’re going to get there in the end though!

Amber: We are! We absolutely are.