“There is something very seriously wrong when the government of a democratic country, like Britain, proposes to restrict the right to protest,” says Peter Tatchell, one of the UK’s most prominent human rights campaigners. “That’s a threat to all our civil liberties. It’s the attempt to render protests illegal, or if not illegal then ineffective. It’s about strengthening the state at the expense of the individual. We have got to fight back to defend the right to protest. It’s fundamental to a democratic society.”

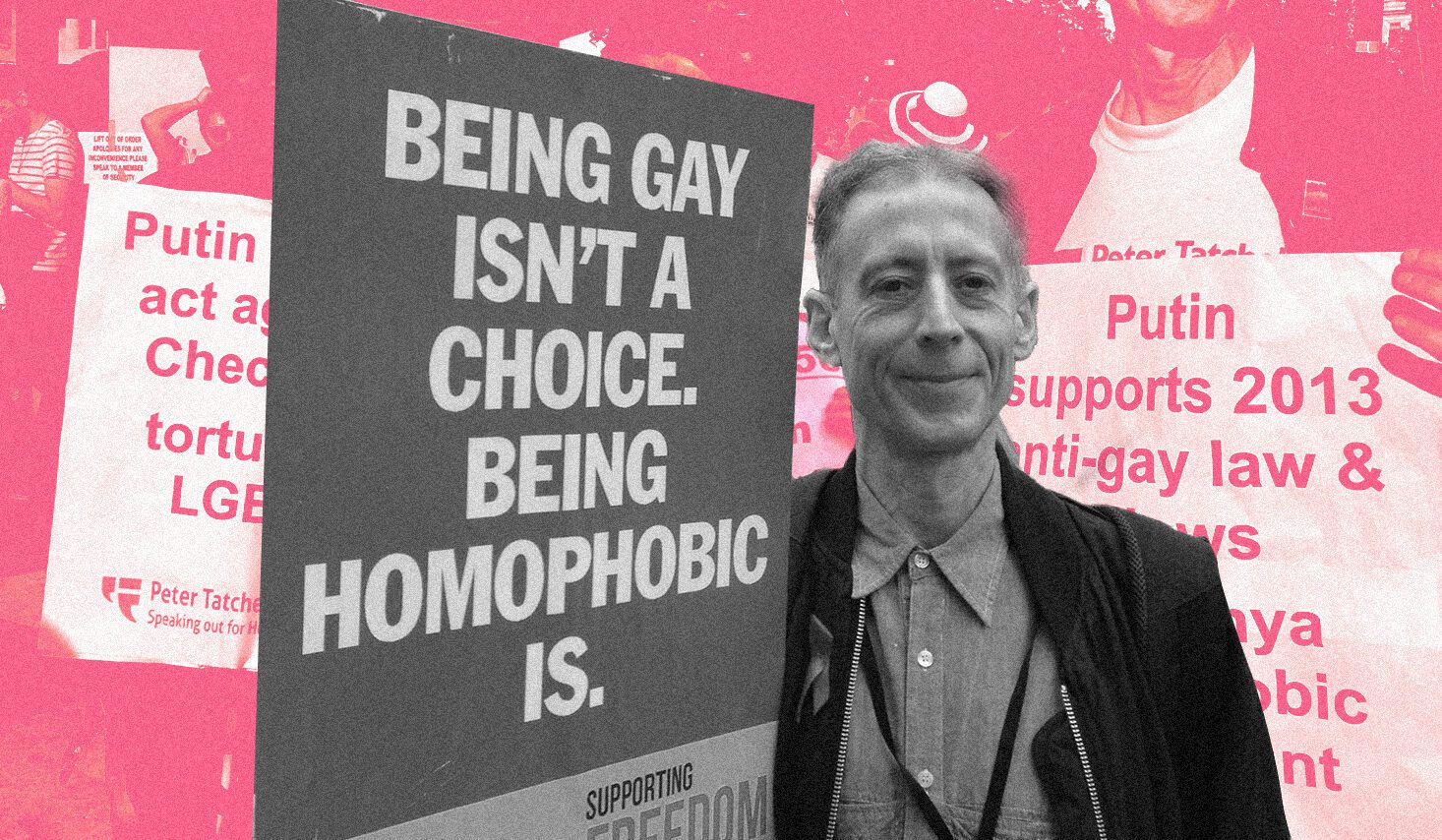

The mention of the current Conservative government’s recent proposal to grant the police greater powers to restrict peaceful protest in the UK has stirred a fire in his belly. Peter is about to celebrate his 70th birthday and mark his 55th year of human rights campaigning. He has been there from the very start of the modern Pride movement, and continues to be a leading voice in the LGBTQ+ community and our fight for equality across the globe. His contribution of decades of work has helped us get to where we are today, and he has no plans to stop soon. The fight continues with many serious challenges still facing LGBTQ+ people in the UK and internationally – and one of the most fundamental ways to ensure that change is through protest. Peter is a living example of that fact.

When Peter Tatchell first moved to London in 1971, the UK was “almost a different country”. He had started human rights campaigning four years earlier at the age of 15 in his hometown of Melbourne, Australia. But when he heard of the Gay Liberation March in New York City following the Stonewall uprising in 1969, he immediately understood what his calling in life was to be. In Melbourne, he recalls, “there was no LGBTQ+ community, there were no gay switchboards or helplines, and definitely no campaign groups.” He packed his bags and headed for the UK where attitudes towards the LGBTQ+ community were intensely negative. “Male homosexuality had been partly decriminalised in England and Wales in 1967, but the level of arrests of gay and bisexual men had rocketed to even greater than before the decriminalisation. So police harassment actually increased and increased massively,” he says. “There were no openly gay public figures, the media was homophobic to the core. Medical and psychiatric professionals mostly still regarded homosexuality as an illness that required treatment and support.”

The LGBTQ+ community at that time had very little legal protection, and in some instances – including housing and employment – it was lawful to actively discriminate against queer people. Aware of what was happening across the Atlantic ocean in the US, a group of LGBTQ+ people in the UK decided to organise action and begin a Gay Liberation movement of their own. Shortly after arriving in the British capital, Peter signed up as a member after being inspired by the efforts of the civil rights movement. “I looked to the Black civil rights movement and took inspiration from its ideals and methods,” he says. “I reason in my own mind that if Black people were an oppressed minority that deserved civil rights, then the same applied to gay people.” Peter studied the history of the civil rights movement and how long it took for Black people to win their equal rights. From this he came to the conclusion that in the Global North – mainly the US, UK and Australia – it would take 50 years to win equality for LGBTQ+ people. He smiles: “That was a speculative guess and it turned out almost right! The Black civil rights movement had a massive impact on me and its methods of peaceful direct action and civil disobedience continued to inspire my work for LGBTQ+ rights.”

Little over 18 months after it first formed, the UK branch of the Gay Liberation Front decided to hold the country’s first ever Pride march. There had been many marches for LGBTQ+ rights before, but this was the inaugural protest that would become part of the modern global Pride movement. “A group of us in the Gay Liberation Front felt we had to counter the levels of internalised homophobia within our community, where many LGBTQ+ people were ashamed of being gay,” Peter recalls. “They were ashamed of their sexuality and gender identity so our counter to gay shame was Gay Pride. About 30 or 40 of us began meeting to plan Britain’s first ever Pride parade.”

I was terrified of being arrested and possibly jailed, though I knew that the struggle of LGBTQ+ rights wasn't just a British one, it was an international fight.

They had no idea if the Gay Pride parade would even work, but set about promoting the event. The response they received from within the community wasn’t great. “Back then the overwhelming amount of LGBTQ+ people were closeted, shameful and didn’t believe they were entitled to equal rights,” says Peter. “I can remember a GLF march to the gay pubs in Earl’s Court to advertise and promote the first Pride parade, we were booed and jeered by many of the gay patrons at the Coleherne Pub. The management ejected us from the property. Well the management wouldn’t allow us to leaflet their customers and ejected us from the premises. As we left, some gay men threw coins and beer bottles at us. They said we were extremists, they said that demanding equal rights for gay people would only draw public attention to us and result in further oppression. Our view was that unless we fought for our rights, we’d continue to be persecuted and harassed forever.”

On 1 July 1972, approximately 2,000 people marched through the streets of London in the name of Gay Pride. Those first handful of Pride marches in the UK in the 1970s were not easy. Society continued to oppress and discriminate against LGBTQ+ people, further compounding internalised homophobia within the community. “The prevailing social view was that being gay was bad, mad and sad,” says Peter. “So in the Gay Liberation Front we came up with a counter slogan which was Gay Is Good. Those three words were revolutionary at that time. It turned upside down the prevailing consensus that gay was very, very bad. It helped us ignite a sense of pride and self worth, confidence in who we were. Over time that makes a formation of a community which hadn’t really existed before up until that moment.”

In his brilliant Netflix documentary, Hating Peter Tatchell, it takes a look at the many moments the activist has put his physical safety at risk in the name of human rights campaigning. He’s suffered serious injuries and damage to his brain, as well as facing the very real prospect of being imprisoned abroad. But it was one of his earlier acts of protest where he felt most concerned for his personal wellbeing. “I can remember staging the first LGBTQ+ protest in a communist country, in East Germany, in 1973. I was 21 years old. I was terrified of being arrested and possibly jailed, though I knew that the struggle of LGBTQ+ rights wasn’t just a British one, it was an international fight,” he says. “Taking the battle to communist countries where LGBTQ+ organisations were banned struck me as very, very important. In the end I was arrested and interrogated by the Stasi, and for a while I thought I’d end up in prison for many years. But luckily my western passport and media publicity pressured the East German authorities to let me go.” But despite the huge personal risk, the protest left a lasting legacy. “The ideas of gay liberation spread to what was then the Soviet Union, now Russia, and to other Eastern European countries that were under communist rule,” he adds.

As recently as June 2018, Peter returned to Russia for a one-man protest in Moscow’s Red Square where he raised awareness of the government’s discriminatory laws against LGBTQ+ people on the first day of them hosting the FIFA World Cup. He was promptly arrested and later released. In Hating Peter Tatchell, those close to him worry that another serious physical altercation could lead to further lasting damage to his health. But when I ask Peter if he’d still travel to countries to protest for LGBTQ+ rights he is quick and firm: “Absolutely! I may be 70 but the battle for LGBTQ+ rights goes on. I plan to continue for another 25 years.”

That steadfast spirit of resilience and perseverance took Peter through one of his most challenging decades. In the 1983 Bermondsey by-election, Peter stood as the Labour candidate hoping to take his hunger for social and political change to the heart of Westminster. The campaign was brutal and is described on Peter Tatchell’s website as “the dirtiest, most violent and homophobic election in modern British history.” He lost and never managed to realise his political ambitions. The 1980s hit the LGBTQ+ community especially hard too. The AIDS/HIV epidemic affected a generation of gay and bi men, while Thatcherite Britain was punishing for marginalised communities. Peter showed up every day to fight prejudice and inequality. From writing AIDS: A Guide To Survival as a vital resource for people wanting to find out more about the deadly new virus, to setting up the UK AIDS Vigil Organisation to better protect those who had acquired HIV, with nearly 20 years of activism under his belt by this point, Peter was equipped with the know-how to speak up and act. In 1988, the Tory government brought in Section 28 prohibiting the teaching of LGBTQ+ identities and experiences in schools. This raised the discrimination LGBTQ+ people faced even higher, with a legal system that refused to protect and support those who needed them most.

All of this led to Peter and 30 other people to found OutRage! in 1990. This new radical queer human rights group were prepared to take extreme action to fight injustice. “What prompted the formation of the organisation was the fact that the police were intensifying the harassment of our community and often doing very perfunctory, inadequate investigations of gay bashing attacks and murders,” explains Peter. “We were outraged that the police were persecuting us and not protecting us.” OutRage! fought for many causes, but one of their initial key demands was simple: “Policing without prejudice”. Instead of adequately investigating the many murders of gay and bi men at the time, the police were arresting members of the community for consenting to same-sex behaviour. “The offence of indecency between men, the same law that sent Oscar Wilde to prison in 1895, was still in the statute books when OutRage! was born in 1990,” adds Peter. “It wasn’t repealed until 2003.” Peter says that “nearly 2000 men were convicted or cautioned for that offence” in 1989, which was almost as many as in 1954/55 when homosexuality was illegal in the UK. “It was that kind of injustice that spurred the formation of OutRage! We ruled ourselves on the nonviolent direct tactics of the Black civil rights movement in America and also were inspired by the suffragettes and their campaigns for votes for women in Britain. Stonewall had been formed the previous year but its tactics of lobbying were not getting any results, that’s why OutRage! resorted to direct action protest. We knew that we had to shake up the establishment, to challenge it, to call out its discrimination that we face.”

By the time OutRage! formally disbanded in 2011, many of the protections and equalities they had protested for had been won. Homosexual offence laws had been repealed, there had been some kind of reformation within the police in its approach to supporting LGBTQ+ victims (despite there still being so much more to do) and we had civil partnerships for legal unions, with same-sex marriage just on the horizon. None of this would have been possible if it wasn’t for Peter, OutRage! and so many other human rights campaigners. “Every single right and freedom the LGBTQ+ community has won began with protests,” says Peter. “We were faced with governments that ignored the persecution and discrimination that we were facing, so we had to protest. Protest has been central to progress for our community.”

Their attempt to divide our community is so destructive, it damages all of us. It's shocking to think of the way in which the LGB Alliance is supported by so many misogynists, homophobes, transphobes and conservative and far right extremists.

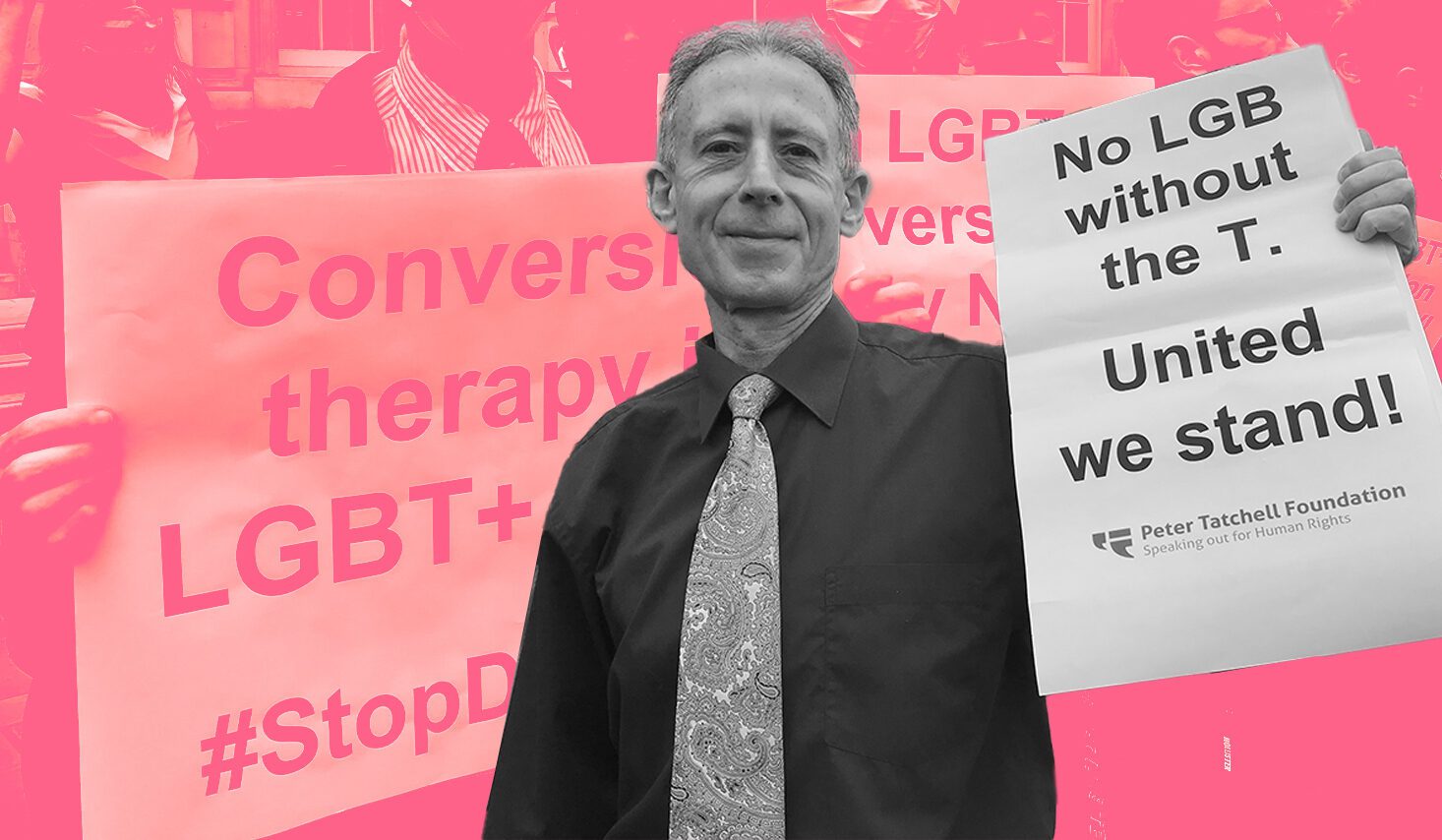

But there’s plenty more progress yet to be made. In recent years, Peter has been a vocal critic of the Tory government’s unwillingness to protect all LGBTQ+ people. When a consultation regarding the reformation of the Gender Recognition Act saw a majority agree that trans and gender non-conforming people should be given the right to self-identity, among other legal protections, they dismissed it entirely and decided not to act. “Under the former prime minister, Theresa May, the Conservatives promised reform, but now they are blocking it,” says Peter. “That is so outrageous. It’s not only a denial of trans human rights, it’s also a broken promise. Trans people have been part of our community since the beginning. Attacks upon them are attacks upon all of us. People sometimes say, ‘Well, trans is different from lesbian, gay, bisexual.’ That’s true, but we also share the common experience of being marginalised because LGB and T people are all gender non-conformists. We don’t fit in with the way men and women are ‘supposed’ to behave. That gives us the common interest in stemming together to fight both homophobia and transphobia.”

Considering his decades of campaign work for LGBTQ+ rights since the very beginning of the Pride movement in the UK, I ask if he was surprised in recent years to see an anti-trans group like the LGB Alliance form. Made up of a small group of gay, lesbian and bi people (along with some LGB ‘allies’), their trans-exclusionary motives are completely at odds with the fundamental aims of LGBTQ+ liberation. “I was shocked by the LGB Alliance with their strident anti-trans agenda,” he admits. “Their attempt to divide our community is so destructive, it damages all of us. It’s shocking to think of the way in which the LGB Alliance is supported by so many misogynists, homophobes, transphobes and conservative and far right extremists. The fact they’re now being backed by the Conservatives and right wingers ought to give them cause for thought. The trans agenda is being used by Boris Johnson’s Conservatives to wage a culture war, to divide and weaken the LGBTQ+ community. That’s why we have to resist it.”

Boris has also been kicking the can that is the banning of conversion therapy down the road for far too long too. It’s coming up to nearly four years since the Tory government promised to outlaw the damaging practice, and yet barely any action has been taken. Peter has been supporting the Ban Conversion Therapy Alliance, working with them to continue to apply pressure to have the law changed quickly. “Conversion therapy is a flawed prospective, it doesn’t work,” he says. “There have been dozens who claim to have been cured of homosexuality through conversion therapy, who have later been exposed as resuming same-sex relationships. At the bottom line conversion therapy simply does not work. It is conning people into believing firstly that homosexuality is wrong, and secondly that therapy can cure it.”

All of these key issues are vital in securing further legal rights for LGBTQ+ people in the UK; a country which is perceived to be relatively safe for our community, but actually has a fair amount more to do. Reforming anti-LGBQ+ laws and calling for greater protections are key messages that should be at the forefront of the Pride movement. But while Gay Pride began as a movement designed to make a huge amount of noise to enact real change, the irony is that the modern reality of Pride is that it’s making too much noise – through music headline acts, carnival-style floats, and diluted mainstream messaging – that it is drowning out important LGBTQ+ issues and the voices of marginalised communities. The commercialisation and festivalisation of Pride has turned it into a sea of white, cisgender, able-bodied torsos that leaves very little space for crucial community-focused campaigning. Pride itself desperately needs to be reformed.

In 2021, the Peter Tatchell Foundation organised the Reclaim Pride march in London, after the Pride in London parade was cancelled for a second year. “We wanted to rebuild Pride by and for grassroots organisations, and our goal was to put LGBTQ+ human rights centre stage. So we marched with clear demands like a ban on conversion therapy, reform on the Gender Recognition Act and the decriminalisation of homosexuality worldwide. Those kinds of demands have never been promoted by Pride in London for decades. It’s just become a big party. Now I am all in favour of a party, but with a human rights dimension. The battle for LGBTQ+ rights is not over. Pride is an opportunity to promote our ongoing demands for equality and liberation. The problem is, the Pride organisers won’t do that. They don’t promote LGBTQ+ human rights – that’s a missed opportunity. Pride could be an occasion to profile LGBTQ+ human rights demands and get masses of media coverage from it.”

More than 2,500 people turned up for the Reclaim Pride march last July, which was put together at just a month’s notice with a budget of less than £1,500. “It was a joyous celebratory march, but it also had a very strong queer liberation message,” Peter adds. “Everybody who joined us said that it was the best Pride they had been to in years.” Peter is highly critical of Pride in London, but mainly through frustration of feeling disregarded and a lack of transparency. “Pride in London has lost the plot,” he says. “It’s not accountable to the community. We think there is a place for a Reclaim Pride march. We would love Pride in London to reform itself but all of our attempts have been rebuffed. We wrote an open letter to the Mayor of London calling for major changes in the way that Pride is organised. In particular we said it was outrageous that only 30,000 people were allowed to march. Every year thousands of LGBTQ+ people are turned away, they’re banned from marching, which goes completely against the ethos of Pride which is supposed to be open and inclusive for everyone.” The Reclaim Pride march will be back later this summer for a second year, Peter confirms, as they continue to represent grassroots LGBTQ+ organisations.

As we look to the future of Pride, it’s crucial that the climate emergency is at the core of our campaigning as a community. It is fruitless spending decades winning LGBTQ+ rights if we’re not also ensuring the protection of our planet for future generations. “Our planet is threatened with final destruction,” says Peter. “Everybody has to act to try and reverse global warming and that includes our bit to get up with many others. LGBTQ+ organisations and Pride events need to be sustainable, we need to make them green. That means minimising our carbon footprint. As we said in the Gay Liberation Front 50 years ago, all these different struggles for equality and social justice are interconnected. If we all stand with each other, we are collectively stronger.”

Across 3,000 protests, 100 arrests and 300 violent assaults, Peter Tatchell has built a legacy of fighting for a better future. From his infamous attempt at citizen’s arrest of President Mugabe of Zimbabwe in 1999 and 2001, and his protest in East Germany in 1973, to confronting the Metropolitan police across decades of campaigning, Peter has never been afraid to act in the interest of progress. But he never fails to remind you that he is just one of many people who have secured history-making change. And for that young 15-year-old today who is eyeing up a lifetime of activism, he has these words: “I’d cite my motto which is: ‘Don’t accept the world as it is, dream of what the world could be and then help make it happen.’ Nothing will ever change unless we collectively decide to take action to make a change. Protest is the life and blood of democracy, it’s the motor of social reform and change. Not just for the LGBTQ+ community, but for all communities that suffer from victimisation and exclusion.”