As a writer, it’s my job to essentially dictate my thoughts through my talons, onto a page, and what I try and do through all that I write is to spark a conversation, share a lived experience that is often not shared, and make some coin doing something that I adore.

However, over the past three months, I’ve found more and more that the emotional intensity of doing so is incredibly draining and often leaves me feeling waves of disappointment and upset. Not just at the fact that most organisations feel like they can pay freelancers 93 weeks late, but also because of the fact that sharing your lived experiences through your writing, and then having to live them again the second you take your fingers away from the keyboard, can leave us feeling unfulfilled, especially when we write about allyship and how to essentially, treat non-binary and trans people with the respect that we deserve and need.

As a social change-maker and activist, many of us fall into this role, not out of choice, but purely due to circumstance. If we have a voice and aren’t afraid to share it, that is a choice. However, nine times out of ten, that choice comes as a result of a burning need to share our voice, because we need help. We need help from people to be able to live, thrive and succeed in the institutions that we work in, because they aren’t made for us to exist within them. Social media can orchestrate an image of activism as being abundant with press trips, fancy dinners and empowering talks, and although that is true, we eventually arise in these situations because we have had to deal with trauma, pain and suffering that we don’t have a choice whether or not we surround ourselves with.

What people don’t see is the scarring and life changing incidents that lead us to being so unapologetic and vocal, yet we are always seen as the people that need to educate and help. We are put so high on a pedestal of liberal awareness that we are trapped under the ‘woke’ ceiling, when there are people around us in the world that aren’t even doing the bare minimum, and aren’t called out on it. We are constantly squeezed and juiced for our energy and our output with questions on how to be a ‘good ally’, that we can find ourselves just regurgitating the same words, the same thoughts and the same opinions, only for them to fall on deaf ears. When really what we need is our words to hit you in the heart with the same amount of power, strength and disruption that they left our tired mouths in.

Related: Reclaiming the word ‘queer’: what does it mean in 2019?

And what this does is make me, as a non-binary person, set the bar for cis people, and specifically cis men, at such a low level that if a cis man doesn’t verbally or physically abuse me in public, then I uphold him as the paragon of man. A beacon of cis light. FINALLY! AN ALLY! When in reality, cisgendered people (and again specifically men more so) aren’t even doing the bare minimum. We are left to mother them into being good people. The power and energy it takes to literally just explain to people how you want to be treated is both empowering and disgusting all in the same instance. It’s an act of empowerment at times for me, as I am often sharing these words in a space that is outside of the liberal echo-chamber that we call Instagram, and that is often a great opportunity to allow people who are marginally engaged in social politics, a chance to broaden their horizons and be a supportive ally to trans and non-binary people. However, the much sharper side of the double edged sword cuts deep.

It’s walking into a room full of people that you know, from the outset, aren’t listening. It’s writing for a publication that you know is already taking ‘a bit of a risk’ by allowing us to share our lived experiences. It’s opening up the comments section. It’s logging onto Twitter and checking your mentions after you’ve basically just written out your most recent therapy session for pocket money from some of the world’s biggest media outlets. It’s about realising that although yes, we are doing amazing work, at the same time the lovely scent of ‘eau de imposter syndrome’ is being doused all over us like a 16 year old boy with a can of Lynx Africa. We can often be our own worst enemies, and that’s one of the biggest hurdles that comes with writing about your life, and your community’s experiences for a living. But it isn’t the biggest.

I’m on the tube home after a gloriously self-indulgent Sunday. I’ve had a cocktail and a cheeky flirt with a waiter in Soho when I get on the tube and whip out a good book, switching on a bit of classical music to set the mood. It’s quiet, and there’s one man sat a few seats down from me. Three stops into the journey and a group of young men get on and immediately charge over to the empty seats opposite me, sit down and lean forward to analyse me. I’m wearing a trench coat, sequin trousers and a roll neck (standard) and I look magnificent (again… standard). My visibly queer appearance is enough to set them off, as they parade around me shouting, asking if I’m ‘a man or a woman’ or if I’m ‘a tranny’. I look up, hurt but not broken, as this isn’t new. My brain re-aligns and my body falls into its usual response to abuse. I am here, alone, and these men are shouting at me, which is as familiar to me as days that start with a sunrise and end with a sunset.

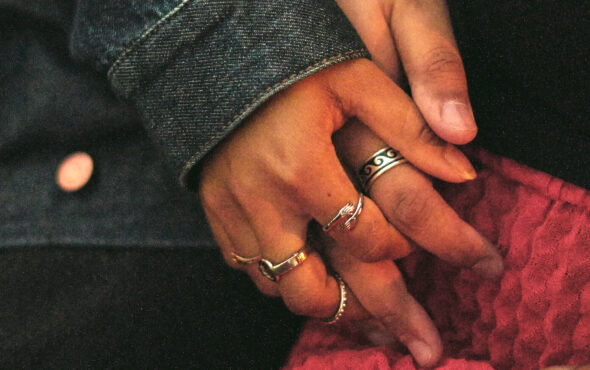

I look up, without fear, and say nothing, for a look is enough for me to feel powerful and above this routine situation. I look into their eyes, smile, and gaze back down to my book, when suddenly the man sitting down from me stands up and sits next to me, putting his hand on mine without saying a word. He doesn’t take his eyes off his phone, and continues to sit with his hand atop mine. I’m shocked. In a somewhat saddening train of thought, I was more jarred by this man’s actions, than the actions of the transphobic babies sat opposite me. The men continued to ask the same questions, and began directing their vitriol towards my newfound accomplice, asking him if he was my boyfriend (obviously part of me wished, but definitely not the time or the place). We got to the final stop where the train terminates, and he pressed my hand, as if to say ‘wait for them to go’. Without saying a word they got off the train and we were left. His hand left mine and we disembarked, me still in shock, him also a little bewildered, but still compassionate and empathetic. We walked to the next platform in our cat and mouse game of ‘avoid the transphobes’ and en route, I thanked him. “I’ve never had anyone do that to me before.” He instantly thought I meant the abuse, and I stopped him and said, “No, I’ve never had a stranger be such a visible ally. Thank you.” We parted ways. I was alone again, but waited so that I would still be on the same carriage as him.

It wasn’t a lot. A handful of words were spoken. There wasn’t even major hostility. But it was enough. It was for someone else to realise that I was vulnerable, and alone, and stuck. And although I felt powerful, and in control, we see time and time again how we so often feel in control, but are then killed for existing. Murdered for living our truth. Beaten for being ourselves. But I will never forget that moment, of a human touch in a time when I needed it most. Now I could sit here in this ridiculously expensive coffee shop as I write this, (a bit emotional now to be quite honest) and tell you a list of things that you should do, but I don’t want to. It’s not my job to tell you how to treat me with respect. It shouldn’t be my job to have to explain why I should be saved from hostility. From abuse. From being killed. That’s a job for you. And now we need you to stand up, step up and be there, because one day if and when you finally decide to be there for us, we won’t be here anymore.

Follow Jamie on Instagram here, and sign their petition to allow people to identify outside of ‘male’ and ‘female’ on legal documentation here.

Illustration Fernando Monroy

Photography Matt Parker