As the writer Rosanna Mclaughlin so beautifully and bluntly states, “The truth is, I can’t recall a time when the concept of community has been placed in so much doubt.”

Under a matrix of both external and internal factors the queer landscape is being threatened silently from within and noticeably from without. Since the millennium rising costs catalysed further by the 2008 financial crisis have led to gentrification flourishing whilst LGBTQ+ bars depleting in existence. One website report illustrates this, using images from inside a non-existent magazine, they tracked and traced or rather identified the many LGBTQ+ venues which no longer exist, recording that around 116 venues specifically in London have closed between 2000 and 2016. Forced out of dedicated communes, and allured by the digital scene, the question is if we have no access to dedicated spaces where do we go physically?

This idea of belonging and imagined private utopias were characterised in the subvertive explorations of the mid-twentieth century works of David Hockney’s pictorial escapes in Domestic Scene (1963), retreats in his Cavafey poetry inspired The Beginning (1966), or differently in a more sexually liberating yet overtly violent esoteric excess William Borough’s novel Wild Boys (1971). However courageous in their time for avocation for same sex relations, in retrospect collectively they portray queer visibility as lacking in outward empathy and visibility for others. This has become confounded.

Such manifestos for a vision for a supposed utopia doesn’t widen for the inclusion for lesbians, transgender and BAME individuals. Also how does their context fit within the queer landscape of today given the lack of presence for others, especially where historically queer spaces and our representation are largely tailored and dominated by cis white gay men. This hasn’t largely been questioned to the extent till now in which Rosie Hastings and Hannah Quinlan’s practice observes and rightly exposes.

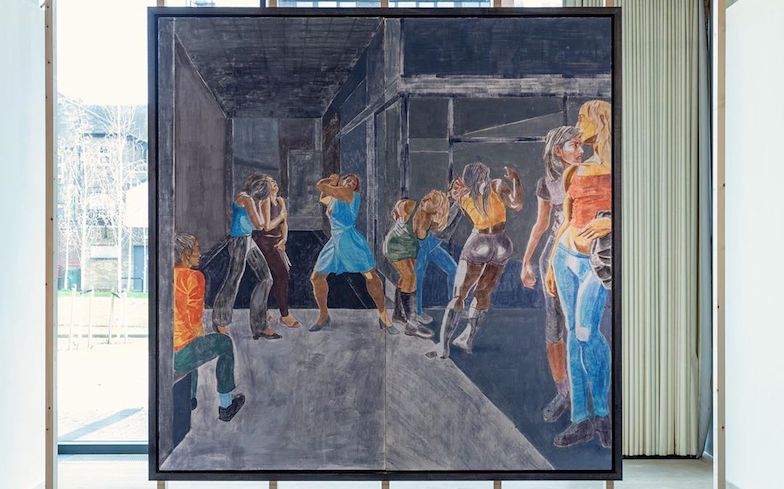

Following on from their participation in the group show ‘Queer Spaces: London, 1980’s – Today’ at Whitechapel Gallery, London last year, Hastings & Quinlan’s debut institutional solo show at Focal Point Gallery in Southend brings to our attention this paradox of representation. ‘In My Room’ explores the false sense of commune that is too often portrayed by these spaces and the urgency that is required for others. Republic (2020) for example, a fresco painting based upon the drawings of Christ being whipped in public by the artist Andrea Mantegna, is instead subverted and dominated by women in expressions and scenes of distress often directed towards and for the audience to surmise.

Similarly graphite drawings depicting women either scuffling or embracing outside gay bars which are destined for closure appear too as episodes of inflations. It is this confusion and division which is proliferating now in queer politics such as the presence of anti-trans rights fringe groups highjacking pride parades. This is dumfounded given that the rights that many of us have today were paved by trans women in the stonewall riots. Like their work Lonely City 2019, which portrayed dance floor conflictions between sneering gay men and friends, amongst all our insecurities and strive to love and exist, we are reminded that we are all in the search maybe for lust, affection, liberation, space, or love, whether in fantasy or reality.

This sense of search for bodily liberation is a subject of Hastings and Quinlan’s short film In My Room (2020) installed in the main exhibition space. Filmed inside the closed Bar Jester in Birmingham, pole dancers perform and men embrace in front of the fractured imagery of renaissance reproductions on the wall, which at once is both almost reverential and harmonic against the movements of the figures under the fragmented sounds. In a different landscape under the cover of night in woodlands and scrubland often associated with cruising grounds, lies the former army base Shoeburyness Fort. In one scene a line of men perform an intimate almost delicate display. You can’t help but feel under the historical contexts of the military past, machoistic culture, the historical implications of cruising, who actually has permission to exhibit sexual expression. Take for example that in the UK police are seeing 81% increases in hate crimes towards transgender people, as well as increases in the risks associated with transgender people meeting others across apps. In contrast LGB people aren’t largely exposed to this.

Our collective motivations for safe embrace and explorations in gay bars are like ancient bathouses becoming threatened and reinstated as artefacts of the past. As we are seeing, as contradictions of our time as a result of changing work times and living costs, dating apps are removing the need for gay bars whilst at the same time forcing those to use apps because there are no bars in their areas, which are largely catered for men. Gay Bar Directory (2015-16) on display on the Big Screen outside the gallery is a video archive of the empty interiors of over 100 LGBTQ+ spaces. Under the glitter veneer of the walls and altar like adorations of muscular men imagery, these venues are a far cry from being the namesake of queer culture that they once was. With only around 50 left in London the dating app has become the primary means by which queer people now interact and meet each other. The issue with this is that many dating apps exhibit racist and transphobic material spread by users on a platform that is supposed to welcome us. BAME and transgender individuals instead are largely being oppressed by these platforms. Under these opposing systems and spaces designed for queer people, Hastings and Quinlan’s output are a continuing observance of what they say is “concerned with communicating the complicated emotional space that is under threat both from internal and external pressures and failures.”

Like the title of the show suggests ‘In [Our] Room’, when we think about the many idols we had pinned and cellotaped to our bedroom walls to be inspired by, who do we allow and welcome into our narrative respectively? When we seek social connection and expect acceptance we are reminded that we must make and advocate space for others. And in our uncertain and troubled time we don’t need community as such, we need to exercise inclusion for all and empathy. After all without empathy the term ‘community’ is redundant.

In My Room is at Focal Point Gallery, Southend until 31 May 2020.