Karin Dreijer steps out on the west London stage to a shrieking crowd that’s dressed to sweat – despite the winter chill still constricting the city in March – and that will more than likely shed some tears. Several people, clad in leather, lace and latex, are holding rose stems aloft, pre-empting their own rapturous receival of the Swedish musician and producer’s project, Fever Ray. This is the There’s No Place I’d Rather Be tour, after all. For many here, it’s their first IRL access point to the campy, cinematic world of Fever Ray’s third album Radical Romantics – their first record in five years.

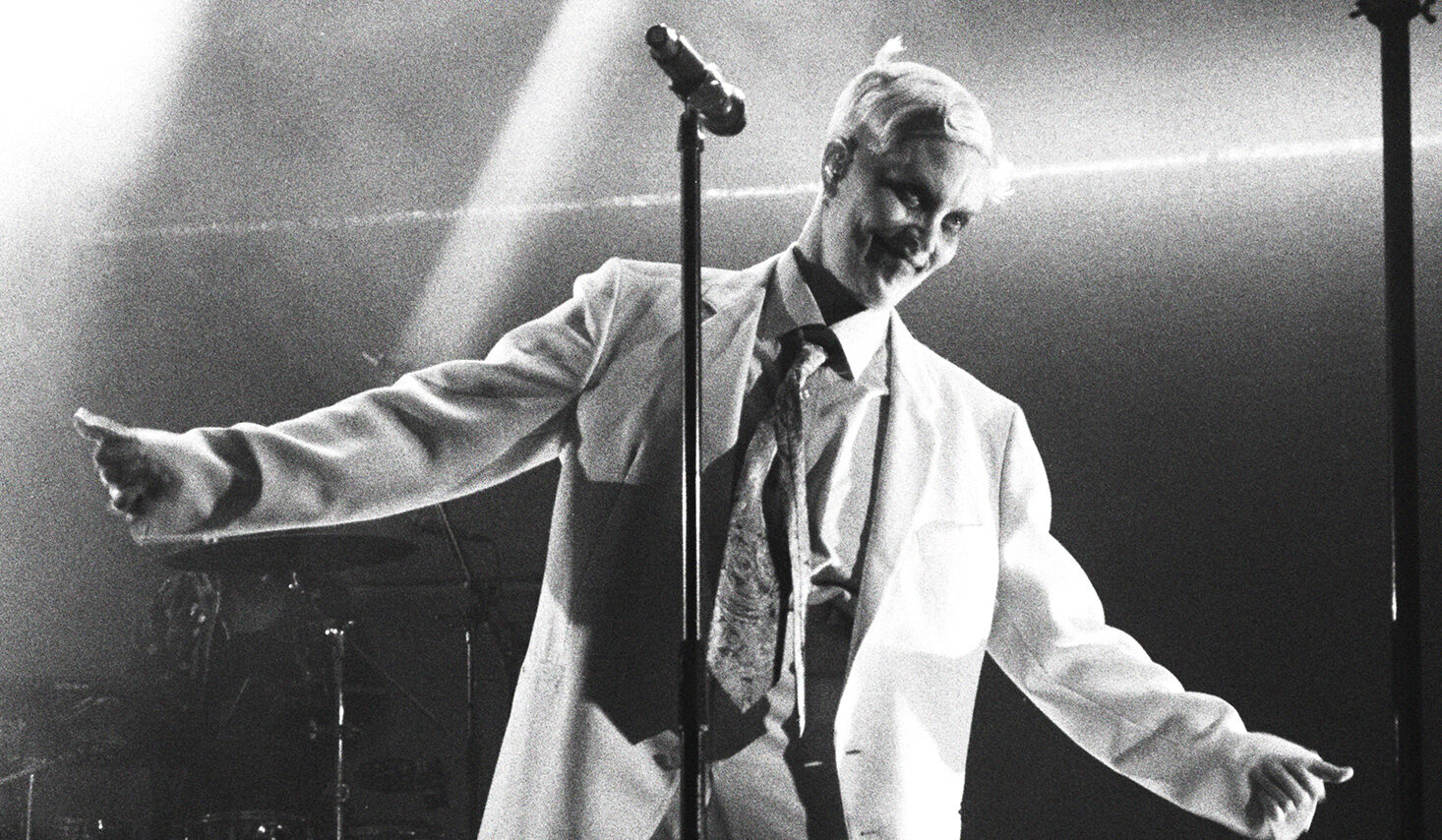

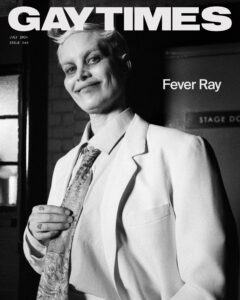

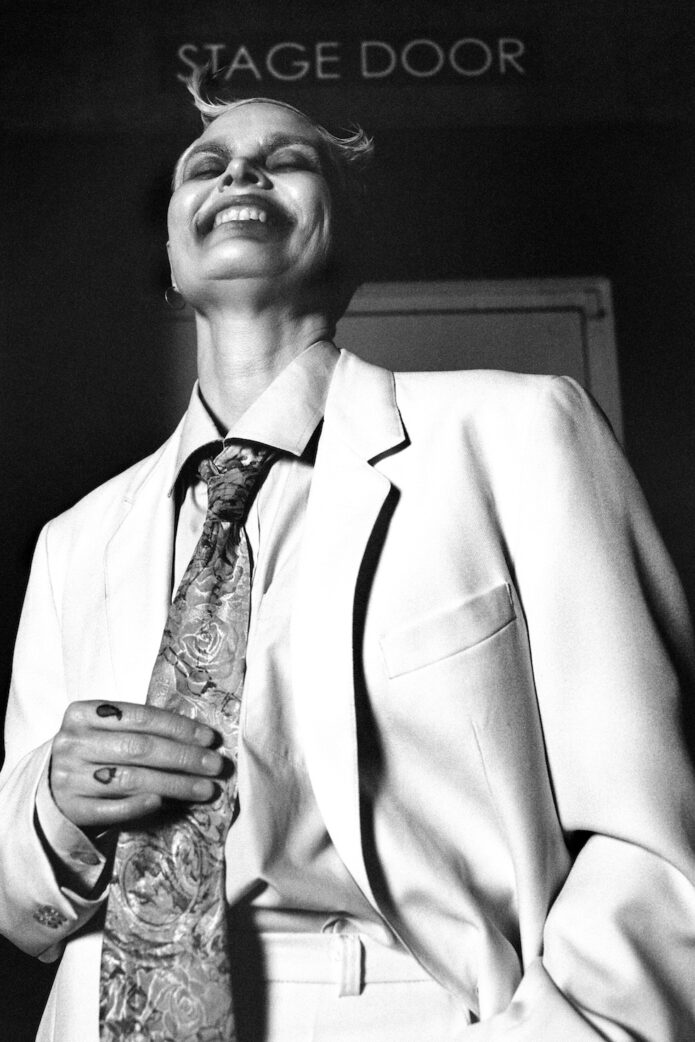

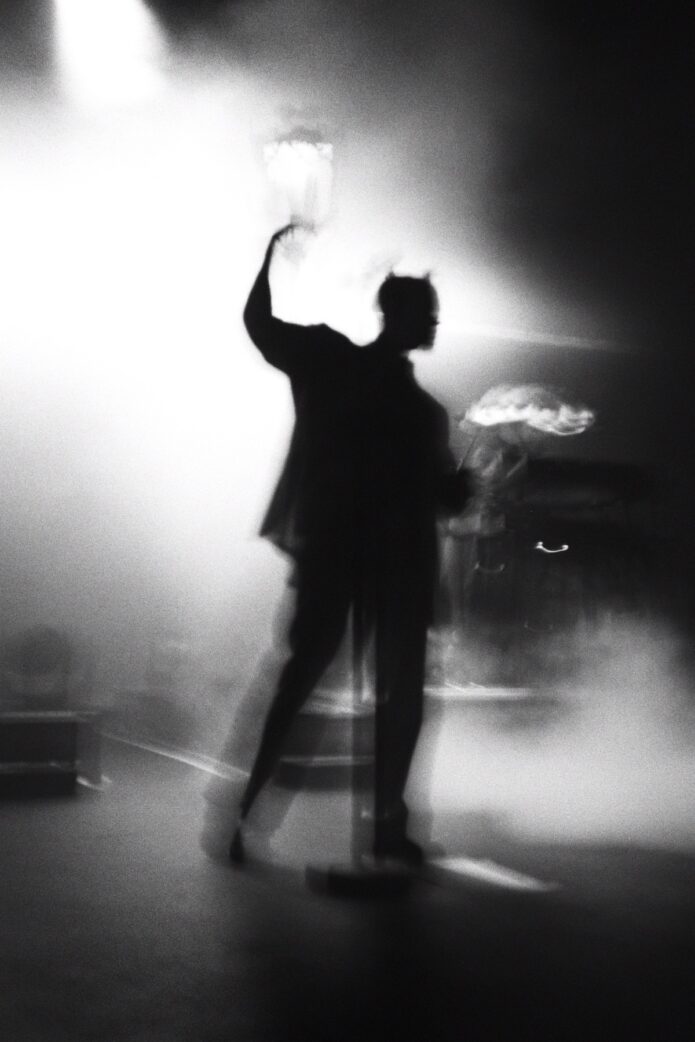

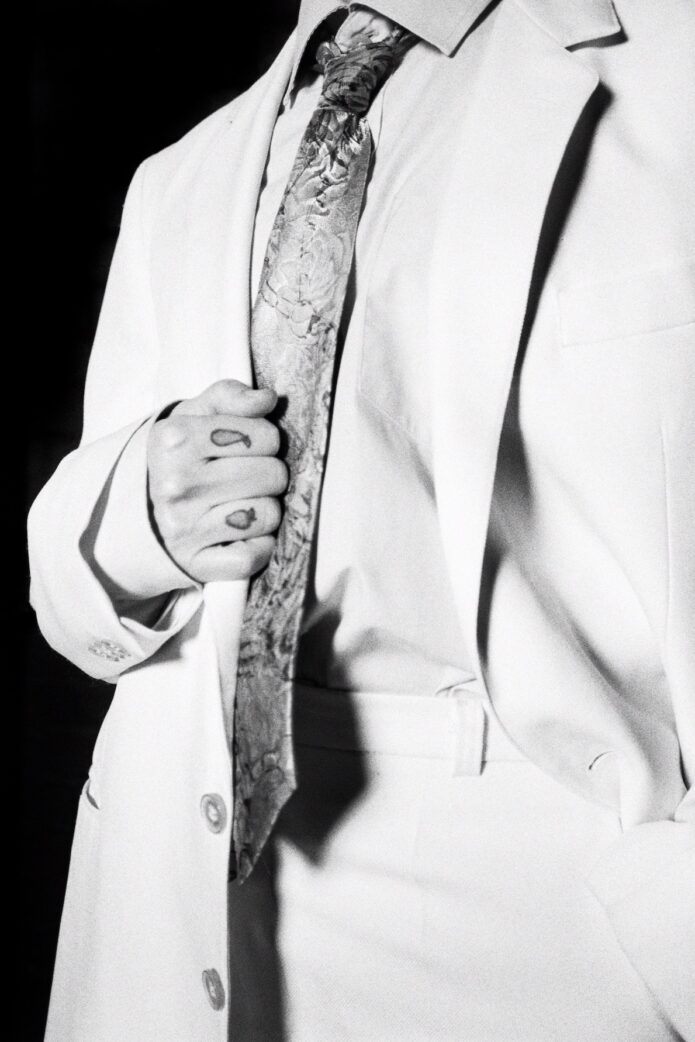

The stage floor is a swamp of white smoke, punctured by a singular street lamp that stutters along to the opening bassy, delirious synths of “What They Call Us”, Fever Ray’s jagged, queer call to action. Dreijer stands in the middle, dressed in a pale oversized suit and tie, a la David Byrne, with pale white makeup and blackened eyes, a la John Waters muse. Their cropped blond hair is slick except for two mis-matched, pronged fringes, like lopsided horns. The band flanks in similarly fantastical costumes, one bobbing behind in a jellyfish-esque headpiece.

“First I’d like to say that I’m sorry,” they sing achingly, baring their teeth between each line. “I’ve done all the tricks that I can”. It’s an urgent track, a necessary guiding hand reaching out through chaos. Across the night, Dreijer commands the stage like an absurd, all-feeling lothario.

Today, I catch Dreijer on Zoom from their Stockholm home – undisguised and sans stage makeup, in a fuzzy knitted jumper. They sit in front of a Keith Haring-esque backdrop on their kitchen wall, speaking with a tentative intensity and taking long pauses. “This tour is the first time I’m really enjoying it… when I’m 48!” they say, bringing their knuckles to their temples. This is a short break, before they embark on a summer of festivals and the Australian tour leg.

Catching Karin Dreijer can feel like both witnessing and performing a magic act. In the boundary-obilitherating electro-pop duo The Knife with their brother Olof Dreijer, they played only a handful of shows, always concealed behind screens. They avoided press, wore masks and distorted their voices in rare interviews. “Why are you so weird?” one interviewer asked the Scaramouche masked pair on camera in 2006. Dreijer has spoken previously of their anxieties around performing, and their perplexity at the cultural fixation on artists past the performance. Then in 2009, they dropped the Fever Ray debut album: a stark, mesmeric solo record that dove headfirst into more ominous sounds, and rewarded listeners who ventured into its cavernous soundscapes with Dreijer’s primal vocals made pleasingly elastic by electronic manipulation. New thematic terrains of domesticity and insomnia-pocked parenthood unfurled, topics that were then still a sticking point for pop, and the mundane was made wondrous by their brilliantly weird lyrics on plantlife and dishwater tablets. Those first eerie live shows, like a laser-studded pagan ritual, starred Dreijer in KISS-like facepaint with a band of insects, bird people and a clown.

Despite saying Fever Ray had retired, eight years later and after The Knife’s dissolution came Plunge: a rebel yell for a riotous sexual awakening and embrace of queer desire for Dreijer, that romps across tumultuous electronic beats. A punishing tour schedule followed – doing around 50 shows in six months in 2018 – which caused Dreijer to burn out. They cancelled their autumn shows and cited an anxiety disorder “that always lurks in the shadows”. Dreijer, whether in The Knife or as Fever Ray, has never capitulated to the album-promo-tour cycles expected in the popshere. Radical Romantics has expanded their art into new territories – it is Dreijer at their best, a curious musician and interrogative songwriter exploding and making new the search for love and what it means to love. Contemporary pop demands optimisation and acceleration, but Dreijer’s innovation is on their timeline: organic, soul-scavenging, and has a feel that they truly live the questions their music puts forth. And while Radical Romantics takes us to the club, it’s also slower, more clarified. This tour has also been smaller, more considered, and the crew is tight-knit.

“This has been a lot of fun, but my body is exhausted,” they tell me. This was a tour over two years in the making. Songs were rearranged by Dreijer from all three albums, bolstered by a crew of close collaborators and bandmates. “I try to give everybody as much freedom as I can, while still keeping my vision. We constantly talk about our characters and who we want them to be.” Fever Ray’s current outfit includes previous collaborators like vocallists Helena Gutarra and Maryam Nikandish (who also choreographs), music director and keyboardist Minna Koivisto (and the aforementioned jellyfish-headpiece wearer) and Romarna Campbell on percussion. “It’s getting better and better with a really good group of people and crew now,” they say.

“‘Shiver’ is one of my favourite moments on stage. Helena and Maryam and I stand close, we sway and touch to the lyrics very playfully, and I get to scream.”

They feel like they’ve moved further past their severe stage fright. Makeup artist and designer Johanna Larsson, who has done Dreijer’s character looks for the visuals, taught them to do their makeup, and it’s become a calming pre-show ritual. “I get through a lot of coconut oil after a show!” They have leaned into choreography they once found feared: “I only really started dancing in 2013. Now I can, sort of, look forward to it.”

The show, still, is evolving. And it’s a collective work. “Creating a space for queer joy takes time, and there has to be communication, with our band and our audiences,” says Dreijer. It’s always a discussion I want to have – what do you think is fun? What is your secret wish, your personal want? What would you like to perform on the stage? We create this comfortable, safe space that remains fun and free.”

“I enjoy the very different parts of my work: the solitude of studio time, and touring with 15 of us travelling together in a bus and performing for fans. To come home, I have to have something to do. I’m not good at resting or doing nothing. My time off so far has been nice – but that’s time in the studio. And repotting my plants.” They’re tight-lipped about it, but Dreijer is working on a score for a film. They do show me said plants though.

“When I work on movie soundtracks it opens up my mind in different, helpful ways,” they explain. “I don’t make up the stories – I’m reading someone else’s manuscript and trying to accompany their narrative. It’s nice not having to come up with everything, to instead push and prod yourself in new ways. A narrowing provides focus, which sometimes I need. Limitations I can see as liberations.” They’ve worked on films before that haven’t come to fruition or in which their music has been cut, so they reserve anticipation (and we will too).

Dreijer’s whirring mind constellates a sprawling universe for Fever Ray. Radical Romantics is more blunt lyrically, and contemplative in its exploration of love and desire. “I write the lyrics. I consider the stories and let them splay out for me. But music for me is this open space. Where my reality maybe does not matter so much,” they say. And these were never going to be straight forward love stories – they groan, bristle, vibrate. Sexual tension fizzes on “Shiver” – “I want to run my fingers up your pussy” – and “Kandy” taps the uncomfortable, sometimes toxic and all-consuming side of love. Dreijer’s readings of bell hooks’ All About Love inspired the work, a book that taught them love as “a verb” rather than a static state, as much a political force as a vulnerable action.

“For some time I was allergic to the words ‘I love you’,” Dreijer says. “I was like, ‘but what do you mean! What is it! What is it that you want to do with me!’. It’s lazy to imagine that love is the same thing for everybody. People want different kinds of relationships, and people feel that they love and are loved in very different ways. It’s so much to learn. I am still learning. In every new relationship, professional or friendship, romantic or familial, you have to be curious.”

These questions play out in an sprawling visual world, inhabited by a motley crew of characters played by Dreijer. It’s built with Martin Falck, a Swedish designer with his own distinctive style and a deep, over a decade-long friendship with Dreijer that began when they were in The Knife. Dreijer shares that Falck has been working for years on a feature film set a millennia ago in Sweden, which they hope to do the music for too.

“When we start making the videos is when the fun begins,” says Dreijer. “Making the album is so hard. I’m by myself a lot, and I struggle over music for years. Then when I’m done, I get to do the fun stuff with Martin. I’d love to make music videos for every song but it’s too expensive.” They’re both always collecting and sharing references from film, art and history. “Then we have the task of boiling it down to what are the important stories we have to tell,” they say. Our conversation freewheels into all their pleasures, obsessions and interests: Dreijer is watching 17th-century feudal Japan-set drama Shōgun – “but I don’t find it visually interesting” – and Tokyo Vice. They love reading maps, recently exploring old sail routes from Europe to Japan. They’ve not booked a show in Japan yet, but hope to soon.

Radical Romantics produced a pentalogy of videos, each trippier and more twisted than the last. “Shiver” concludes a visual series that confronts the complex feelings of falling in love: the fear, the soul and body-baring, the pleasure. It’s directed and co-conceptualised by Falck, starring bodybuilder Irene Andersen as a Frankenstein-y doctor and Dreijer as recurring character Main. It’s an epic sci-fi, set somewhere between a BDSM chamber and a surgical dungeon. It is also inspired by the ‘Lovers of Valdaro’, 6,000-year-old human skeletons in Italy that were discovered “locked in an eternal embrace” that Falck and Dreijer obsessed over. Dreijer and I spend a not-so-insignificant portion of our interview then discussing the skeletons, Nordic and Irish bog bodies, and the triassic cuddle – a 250 million year old fossil of a protomammal and amphibian in an embrace.

All these references, theories and ideas bolster what you could call Dreijer’s creative playground, but it’s also their forcefield. “I get to play these characters who have no shame, or the same luggage that I do,” they say. “I was assigned female at birth, and that has brought me challenges. As a musician, I can inhabit different perspectives and stories. It is a privilege to have these forms available to me outside of real life, where things can be so heavy. Where you have to think about gender or power. Where capitalism rules and neo-fascism is at our door. I can feel most me [as a character], or when I am screaming like a metal singer.”

Dreijer began publicly using they/them pronouns around 2018. “I feel more free now because I feel closer to my own being,” they say, “but it is not just to do with gender binaries. It is in the many other ways I’ve come to understand myself. Therapy has been a big part of my practice,” they say. In 2018, Dreijer received an ADHD diagnosis that helped them understand how they perceive and function in the world. “It was one of the best things I could have done.”

In therapy, they continue to confront their issues with fear and confidence. “If you have been afraid of things most of your life, it is an ongoing practice to keep on doing things even if they scare you. As I’ve experienced new things, I have found it important to have somebody to talk about the process.”

“I never thought of myself performing as much as I have, lately,” they continue. “I was so afraid of it. And I don’t like to be afraid of things. I have to overcome them. This has taken years, but it’s a good practice. It’s the worst thing to do, to do things you’re really afraid of – but I’ve had a lot of good therapists.”

Today, Dreijer asks: “What is actually giving me energy back right now? What is my self care?” It can change every day. “I should probably say exercise, but I’m so lazy,” they say with a laugh. Having access to Sweden’s breathtaking lakes, forests and parks has been a salve, and before kicking off the tour again, they’ll go skiing with their kids.

Dreijer has two teenage children, one who moved out last year. “It’s very different. I mean, I’m not done with parenting – they need me still, but it’s a different situation. I’m getting much more freedom, which is also a bit scary. What happens when nobody needs me anymore? I think that soon I can live wherever I want in the whole world, but I think I’ve started to realise that I will still want to live close to them. It is amazing to see them form, become humans. I didn’t do a bad job! Then you get life back… sort of.”

They’re not a nostalgic person though. “I like to be where my friends are. I try to be present – but that is also a practice, a difficult one. And I worry too easily about the future, so I try not to think about that too much.”

“I sort of hate looking back,” they add. “I can look at pictures of my kids when they were smaller, but I’m very happy that the past is behind me. I like the idea that every second is a new start, or at least every morning is a new start. There is a possibility to do things in a different way. And I think that’s amazing. It’s a way to be liberated, to think, to survive.”

Fever Ray’s shapeshifting music has become a soundtrack to such liberation, expansive thinking, and survival for a generation of queer people. For Dreijer, it’s sometimes hard to envision that impact. “It’s difficult to grasp, but I know that music was very important for me when I was young. It always will be. I am part of a long history of storytellers in queer performance. I’m very grateful to be just one author in that history. If the stories that we are telling on stage and on the albums make people feel things, that is an honour. There have been so many before us, and there will be so many after us. Gathering through music is a beautiful thing.”

Sweden’s political landscape is currently dominated by the far-right, and it’s on Dreijer’s mind. “It’s crazy what’s been happening in Sweden. The neo-fascist government cut down culture, welfare and schools.”

“I will always believe that everything is political,” they say. “The personal is political. I have a lot of privileges: I am a white person in a good economic situation, and it is something to always be conscious of.” Dreijer pulls the golden thread of political thinking through their creative work and day to day. “Free abortions! Clean water! Destroy nuclear! Destroy boring!” they sing on “This Country”. They signed a letter calling for Eurovision to ban Israel from competition alongside acts like Robyn. In April, they played a Swedish gala for Palestine that also featured Olof and Greta Thunberg. And in Fever Ray, they’ve gathered a talented crew of women and non-binary artists.

Fever Ray speaks to a conception of gender and selfhood that feels increasingly salient. In deconstructing and making new pop and electronic textures, and complicating the human voice, Dreijer also complicates societal defaults, the deeply embedded norms. Radical Romantics and all its theories have been in our orbit for a year, and Dreijer began work on it over two years ago. While it remains a fan manifesto, there’s more work to be done. “I’m already somewhere else,” says Dreijer. “Even before I was done. I had been thinking about it for many years. I am thinking about new things.”

“Music is good if it makes you feel something. You take some time off to allow it to make you feel something, to think, to take a break from routines and everyday thinking. I think it doesn’t have to be so much more than that because that is a lot. Then sometimes you just need music to be for when you have some vacuum cleaning to do. That’s a purpose.”

There’s no Fever Ray music being made just yet though. Rehearsals, costume fixes, and finding replacements for crew will be taking up their time – but any embryonic ideas are talked into Dreijer’s phone for notes. “I’m not near that creative space yet, but I’m good with that.

With no steer clear, what we do know is that what’s next will be anything but conventional. It will be caring and political. And they’ll bring us along for the ride. “When you and everybody around you is under attack, when there’s so many awful, horrible things going on, it feels difficult to take breaks. Who am I to have a break when there are so many things that need done?” Dreijer says. “But we need each other. And we need to stay safe and healthy – maybe that’s a bad word – but we can’t go under. We must take care of each other.”