In late 2021, Becca Cox was desperate to find a place to line dance in New York City. They were fresh off of listening to WNYC’s 9-part “Dolly Parton’s America” series which reignited their childhood love for country music and were itching to get on the floor. They started teaching themselves line dances in their office when no one was around, hitched a ride to New Jersey to buy a pair of cowboy boots, and then found a class in the Ukrainian Village. And then they heard about Stud Country.

“One of the first couple of times they had a [Stud Country party at Brooklyn Bowl] there was a couple that had been dancing together for 30 plus years who was out on the floor,” Cox tells GAY TIMES. She watched the couple glide, arm-in-arm in a two-step under the venue’s massive spinning disco ball. “It was so beautiful to see. Country dance and country music has such a rich queer history that isn’t always acknowledged because of the heteronormative hegemony so being able to reclaim that – even if you didn’t grow up in the South – is amazing.”

Initially a Los Angeles-based event launched in 2021 by Sean Monaghan and Bailey Salisbury, Stud Country is now a U.S. phenomenon with recurring events in Los Angeles, New York City, Nashville, San Francisco and Sonoma. At its core it remains a casual recurring two-step and line dancing night but has also expanded, incorporating workshops in addition to mixers and more formal balls. Its purpose is to preserve a more than 50-year history of queer line dancing captured in the short film of the same name, that some felt was in danger of being lost with the closure of various bars.

“The biggest difference is the LA one is so established in a sense,” says Spencer Pond, who is into the queer history of many dance forms including Lindy Hop. Pond first attended the original LA-version of Stud Country, which is currently being held at Club Bahia, before being recommended to the one in Brooklyn. “In New York it’s still growing and building. Because there’s so many people in New York City, you can come here every week and still find people you’ve never seen before.”

At Brooklyn Bowl, while vintage clips of gay men line dancing played on screens, the night started on the no-drinks-allowed dance floor (you can drink from the sidelines) with partnered dancing – linked couples moved across the space like the impressionable pair Cox first spotted. Susanna Stein, an organiser of one of New York City’s other gay and lesbian country western dancing groups, Big Apple Ranch, then broke down a basic two-step for any newcomers.

“This was the very first time where I felt at home,” says Philip Lau, who started off Western dancing at Sundance Saloon in San Francisco before attending Big Apple Ranch and then Stud Country. “This is where I get to see two burly men dancing with each other in close proximity.” In this queer-specific space, couplings shirk preconceived notions of who should do what and how.

“I’m really tall and I’m a woman-ish so being able to lead is really nice but also being able to follow…” Cox says. “Yes, I’m super tall but if I want to follow there are five-foot short kings on that floor who will lead me. It’s so beautiful to see the subversion of ‘tradition’ and expectation.” But the partnered dancing was only a wholesome precursor.

“There’s nothing hornier on this Earth than watching a couple line dance directly in front of each other"

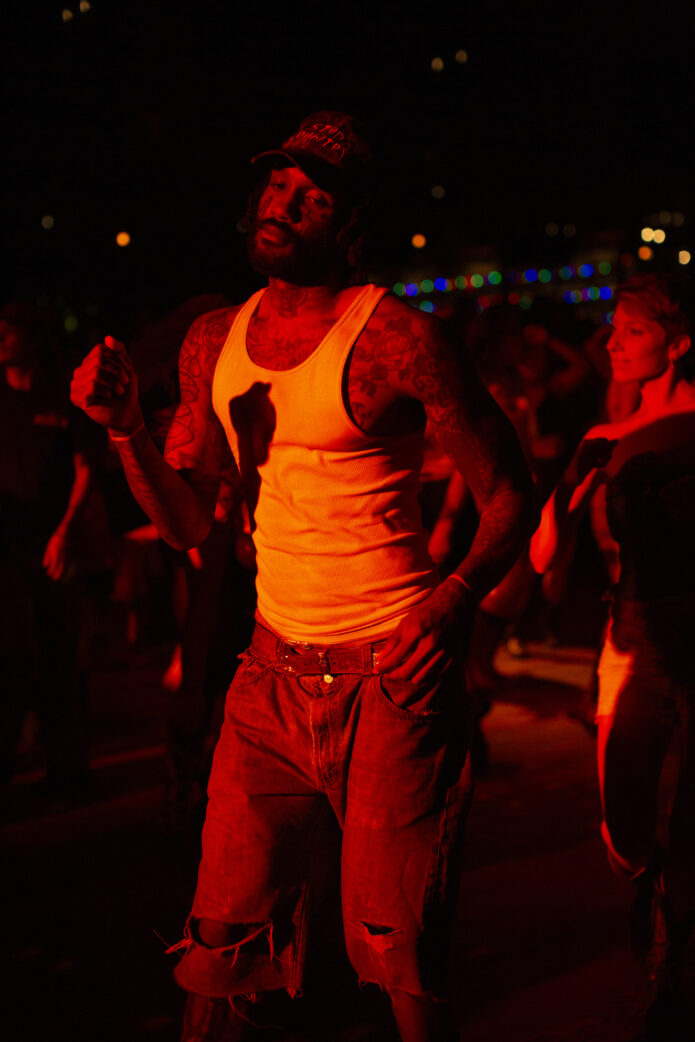

Before long, the night switched to the line dancing segment. With the DJ playing songs like Shania Twain’s “I Ain’t No Quitter” and Shaboozey’s “A Bar Song (Tipsy)” hundreds of dancers packed the floor for a series of hot and sweaty shuffles. Organisers teach two new line dances per night where the assembled kneel so even those in the back of the venue can see the on-stage instruction. But otherwise, regulars throw themselves into the choreography they know from weeks prior.

“To me, line dancing is all about dancing alone together and dancing together alone,” Pond says of the dynamic where though you don’t have to rely on anyone else for your moves, you are still interacting with the entire room. “Every time I’ve been at any social dance event I’ve always been able to have a moment on the dance floor where I make a special connection with someone else where you might catch each other’s eye while dancing and that’s really the moment that I look forward to.”

That connection can feel entirely wholesome and affirming. As a learning-first space, people are quick to help one another out, immediately establishing a level of connection as the learning happens collectively. But it also can become downright steamy. When Luke Bryan’s “Country Girl” came on there was thigh slapping, hip shaking, spinning, and hair tossing as regulars shimmied into a set of choreography that had previously been taught.

“There’s nothing hornier on this Earth than watching a couple line dance directly in front of each other, and they know how to dance up on each other while still doing the choreography which is really hard,” Cox says. “There’s people flagging and really embracing these unfortunately bygone ways of expression and bringing them back.” Flagging is a form of nonverbal communication queer people use the styling of fashion items to indicate sexual interests, often by way of the hanky code which was popular in the 1970s.

Stud Country is a space that doesn’t necessarily feel radical because it overwhelms attendees with joy, fun and a sense of community, but it is. Here, the leaders are those who choose to lead and the followers are those who allow themselves to be led. Apprehension about what others might think to see how your body moves and who it moves for are largely absent. What’s left is pure and largely unbridled freedom.

“I probably wouldn’t have gone if it were a straight thing,” Naomi Linnell, who was attending the event for her first time after participating in a line dancing night in British Columbia. She had come with Cox and other members of their softball team at Cox’s persistent urging. “There’s this history of queer people not being able to dance in public but now we can and we should.”

They added one more thought before running to the packed floor, where another line dance was starting: “And it’s so fun!”