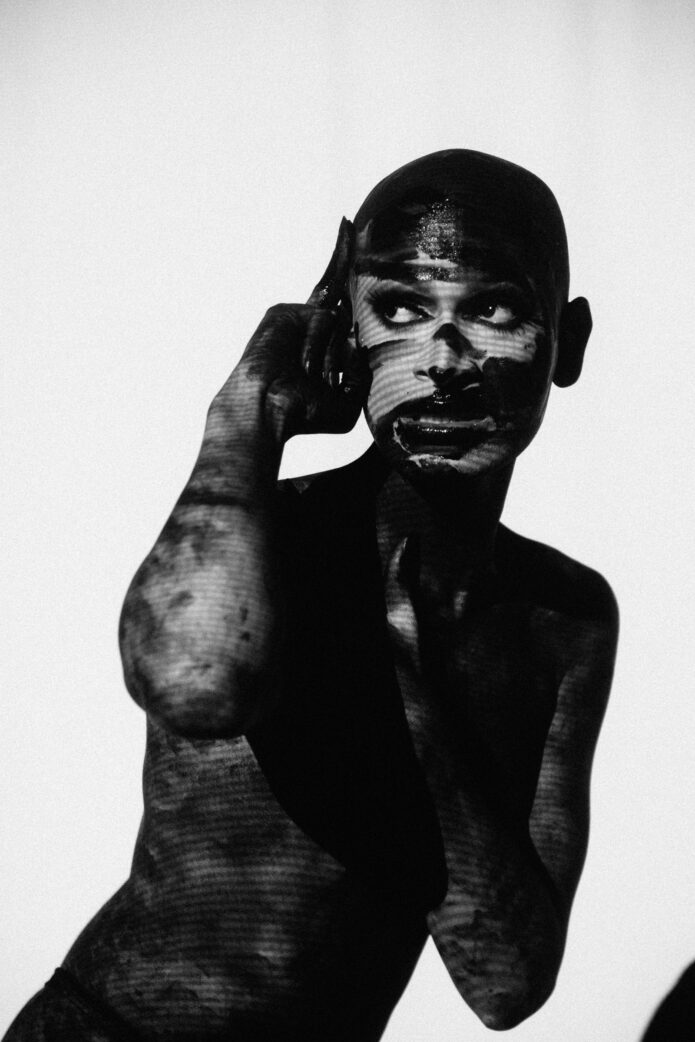

The audience at Le Poisson Rouge was completely silent for four and a half minutes. They watched with rapt attention, practically frozen, with just a few phones held up. At the center of the stage before them was Julie J, her body caked in black paint, slowly and almost painstakingly rising to her feet, then lowering again as the haunting falsetto of Moses Sumney’s “Doomed” seeped through the sound system.

“I’m looking forward to taking more risks in 2024,” J told GAY TIMES later on that night, this emotive performance having been one of those. It was January and we were at NightGowns, Sasha Velour’s famed drag showcase now in its eighth year, for the first night in a six-month residency. Much like J’s, a NightGowns performance is often difficult to completely capture in either words or images: this one in particular was at once mesmerizing, agonizing and supremely sublime. In practical terms, J did little more than stand from a crouch and lower herself again while smearing paint on her face. But as the stage’s single spotlight went dark at the song’s end, the packed crowd erupted into applause and cheers, all having felt the exhausting interiority of the number.

“I think in drag there’s sometimes a fear of doing something that veers out of the norm, that veers out of the commercial,” J said. “But there’s no reason to fear that somebody won’t understand it.” The following night she would take home the coveted Entertainer of the Year title from New York nightlife’s Glam Awards, in addition to three other trophies.

It’s telling that at the latest NightGowns, this Sunday, RuPaul’s Drag Race Season 16 competitor Nymphia Wind remarked that when she was still in Taiwan she would watch videos of NightGowns on YouTube. Since launching in August 2015, the showcase has made itself one of the most coveted places for drag artists to explore acts that might not be appreciated on another stage. Over the years, Velour and her team have cultivated an audience that comes ready to be surprised, which has in turn given a growing generation of queens not only the license but the space to experiment.

“The space that this bitch is holding is unparalleled in this country and the globe,” Brooklyn’s regarded showgirl Charlene Incarnate said on Sunday, following her own performance to Linda Eder’s “Bring On the Men” dedicated to the recently deceased Cecilia Gentili and all sex workers.

While performing at NightGowns is viewed now as a “stamp of approval,” the event got its start at the shuttered Brooklyn bar Bizarre because Velour couldn’t find spaces to put on the numbers she wanted to perform. So she made one. Devotees crowded into that small monthly event, sitting on the floor, trying to get a peek at the magic. NightGowns’ success (and Velour’s own bump in visibility after a RuPaul’s Drag Race win) saw the show move to the relatively massive venue National Sawdust with lineups that swelled from four to sometimes 11 performers. A TV show followed, as did a virtual five-year anniversary blow-out, and a two-week off-Off Broadway musical staged after the pandemic. But last year, the event relocated to Le Poisson Rouge, the legendary West Village music venue, where it boasted a sold-out six-month residency.

“The space that this bitch is holding is unparalleled in this country and the globe.”

“I think one of the goals at Le Poisson Rouge is to kind of bring it back to the NightGowns that we started with where everyone got to do two performances,” Velour says. Sunday featured Drag Race current competitors Nymphia Wind and Sapphira Cristal (Priyanka is slated in the future,) as well as others like the drag king King Molasses and Charlene.

“I kind of missed the intimacy we would get at those shows,” Velour says. “But also as an artist, to get to show two different sides of what we can do is a really exciting opportunity. I think that’s been really successful.”

NightGowns is not a show where the queens kick and split for tips — every queen, including Sasha, is paid the same wage as a result of ticket sales and sponsors (they are always looking for more, if you’re inclined). So without that pressure, the space becomes one where drag performers get to explore work they truly want to create. Take the cathartic 2017 performance Aja put on reckoning with her Drag Race journey to a backdrop filled with screenshots from texts with friends and family as well as nasty comments from fans — not the sort of thing you do when you are trying to get someone to shower you with cash.

In introductory onboarding emails, the cast is encouraged to bring numbers that make them feel empowered or showcase something they love deeply. Sometimes that requires heavy production and orchestration, as chronicled in the NightGowns docuseries — lasers, projectors, floating mirrors, perfectly timed spotlights, and a platform that can be pushed mid-performance around the stage. But other times, the only thing required is body paint.

“This is where you come to see the good drag,” Velour said at her January show this year. In addition to Julie’s performance, there was Miss Malice (a self-described high femme dyke drag queen), the Latine drag king Myster E Mel Kiki, and Sasha. Diversity on the main stage has remained a major point of differentiation for NightGowns even as other drag showcases increasingly prioritize experimentation and an artist-first approach.

“This is the place for everything from high pageant drag to gender bending, punk, grunge drag.” Sasha says. “This is the place where those things can co-exist in one evening. From the very beginning I’ve always tried to have a little bit of everything.”

At her January show, Velour performed an abbreviated version of a number from her Big Reveal tour which heads to Europe in March. In it, she deploys an investigation of camp through a dizzying series of phone calls.

As the performance progresses, Sasha speeds through a variety of songs, audio from films, and viral clips from social media all reconstructed into its own narrative with telephone rings as a transitional device. Along the way she hits Miranda Priestly’s stinging cerulean monologue, the iconic “Leave Britney alone” video, Alexis Neiers tearful call to Nancy Jo about those 4-inch little brown Bebe shoes, Lady Gaga’s “Telephone,” and Faye Dunaway as Joan Crawford screaming “Why can’t you give me the respect I’m entitled to” from Mommie Dearest. The performance is laugh-inducing and invokes the type of moments that demand the audience join in. It really is a perfect illustration of camp, but also an homage to a legend, built on a style of performance from the famed drag performer Lypsinka who first started putting it on in the 1980s and has performed a version of it for NightGowns many times. Lypsinka is often credited as having elevated lip sync performance to fine art.

As with so much of Sasha Velour’s work, there’s always a level of education and history at NightGowns. There is something about the current iteration of the show that seems to reference spaces like the must-see BoyBar extravaganzas of the 1980s and possibly even dinner-and-a-show venues like 82 Club in the 1950s and 60s. These historical connections are always there, whether or not they take center stage.

NightGowns understands how to elevate drag — not as a new proposition, but as a reference to what came before it. It often asks that the audience read performances as creative expression, as a conversation, in lieu of waiting for the chance to hoop and holler at the next jump or reveal. Ultimately, the art of drag is really a signature of Sasha’s. Though many of the most notable Drag Race winners make their name off of performing other talents in drag — comedy, theater, runway — Sasha has always been laser focused on the art of the lip sync. So that beyond the visuals — though the visuals are obviously stunning — you walk out of NightGowns with no choice but to say: Now that … that is good drag.