“Welcome to Japan, come and see the rising sun. Welcome to Japan come and see the rising sun” — this is the start to the 2021 Mizrahi Japan theme song, written by international legendary mother Koppi Mizrahi and her son, Kinshasa. I always get a shudder of excitement when I hear it. The collision of Koppi’s Japanese voice and language (“Look at me, bitch, wakatteiru?”), Kinshasa’s English chant and the vogue crashes remind me of the freshness of watching Japan’s ballroom grow.

Koppi and Kinshasa are two instrumental players in Japan’s ballroom (or ‘house ball’) scene, bringing not only vogue and vogue chants, but holistic ballroom house culture to the country’s queer spaces. And these spaces are all too eager. Like club kids in the mid-2000s and drag queen culture since 2010, ballroom culture is another case of queer subculture exploding as a global phenomenon, attracting mainstream attention with documentary films like Paris is Burning (1990) and Kiki (2016); drama series Pose (2018); and finally the three season-long reality competition Legendary (2020).

While there are ups and downs to such mainstreaming and popularisation, particularly given ballroom’s roots as a space to protect the LGBTQ+ community’s most marginalised, one benefit has been the flourishing kiki and major ball scene in more countries than ever before, including East and Southeast Asian countries like the Philippines, South Korea, Vietnam, and Japan. Koppi and Kinshasa’s music, featuring a blend of English and Japanese slang and the quintessential cocky diva attitude, is representative of the new hybrid communities forming in Japan’s fresh ballroom scene.

Ballroom’s roots

In Harlem, New York, 1970s trailblazer Crystal LaBeija kickstarted the ballroom movement as a sanctuary for Black transgender women (fem queens) and gay men (butch queens) looking to compete in pageants and drag balls without racist white judges.

Through the following decade, ballroom became a rich subcultural space for Black and Latinx queer folk, who founded the first Latinx house, Xtravaganza, in 1982. Beyond beauty and runway walking pageants, ballroom included vogue battles (developed by Mother Paris Duprée around the same time Crystal LaBeija started organising balls), unique gender and sexuality systems that rejected mainstream heteronormative roles like “man” and “woman,” and a found-family system (the houses) for queer youth on New York’s streets.

LaBeija, Xtravaganza, Ninja, Mugler, and Revlon are all examples of ballroom houses that continue to this day. This moment became “expression of the house culture became the ballroom” as Ronald Murray, Father Ron ‘drama’ Xclusive Lanvin and one of the curators of Ohio’s House and ballroom culture, labelled it in his TEDx Talk on ballroom culture and history.

Through the decades in which ballroom existed as an invisible, underground, mise en abyme type of world, participants could escape from a wider society in which they were marginalised to a private society where they were mothers, fathers, victors, and trophy winners. These were precious spaces that returned queer people of colour their dignity and sense of belonging.

As the HIV/AIDS pandemic began, they also became places where queer youth could receive sex education, condoms, and testing. With these elements in mind, as well as the popularity of the different waves of vogue itself, it is unsurprising that ballroom quickly expanded across the cities of the United States and, by the late 80s and 90s, had developed a small but flourishing presence in Europe.

Since then, terms from the queer lexicon – popularised by western LGBTQ+ media such as RuPaul’s Drag Race – like ‘shade’, ‘werk’, ‘kiki’, as well as dance techniques such as hands performance and ‘death drops’ (referred to as dips in vogue) have been absorbed from ballroom dialect and often with some controversy. Given ballroom’s history, the new era of media interest and commercialisation feels invasive and appropriative to many, who are concerned the general public are only interested in the superficial aspects of ballroom or, worse, are weighing into the scene’s debates on gender and sexuality without understanding its history and socio-political importance first.

As time has passed, ballroom has found itself in dialogue with modern radical queer theory. The category of ‘realness’, for example, is one of the oldest in ballroom, and originated as a way to celebrate trans women’s ability to pass and survive outside in the wider world. Today’s queer community looks more critically at ‘passing privilege’. Similarly, ballroom’s gender-restricted categories such as Male Figure (masculine presenting), Female Figure (feminine presenting), Butch Queen (gay male), and Fem Queen (trans woman) can seem conservative and unfriendly to nonconforming and nonbinary individuals. Many longtime participants and leaders of ballroom resent the lack of history and context critics bring to these conversations.

On the other hand, the popularisation of ballroom has brought fame and financial gain to some of the best voguers and commentators (the MC’s who provide rap-like chants and songs during battles). Additionally, the documentaries, drama series, and reality TV shows showcasing ballroom, together with the work of international house leaders, has helped to continue spreading the dance and culture to even more distant countries. Many new participants stepping into a ball for the first time have a frame of reference and general history thanks to consuming these shows, connecting them to global queer history and heritage as a whole.

Welcome to Japan—1990 to 2011

While Harlem’s original ballroom culture grew from the bottom up (organically arising from the needs of New York’s queer community), ballroom in Japan has developed from the top down. Vogue became popular purely as a dance in 1990 with the release of Madonna’s hit song of the same name. This community-capturing song continued to flourish with the work of the first Japanese voguer, Fumi Xtravaganza, and voguing teams like Electro Musique Fusion in Fukuoka prefecture. However, this first boom largely faded by the turn of the century.

By 2005, we saw the debut of a Tokyo-based dance team called ASIENCE, who performed several hit vogue numbers on Japanese national television. This dance team did not spawn the new emergence of Japanese ballroom in and of itself, but the national broadcast did usher in several key figures who would: future House of Oricci father, Showtime Showta, in Hokkaido and future House of Mizrahi mother, Koppi, in Tokyo both saw the ASIENCE performance and became fascinated with their dance style.

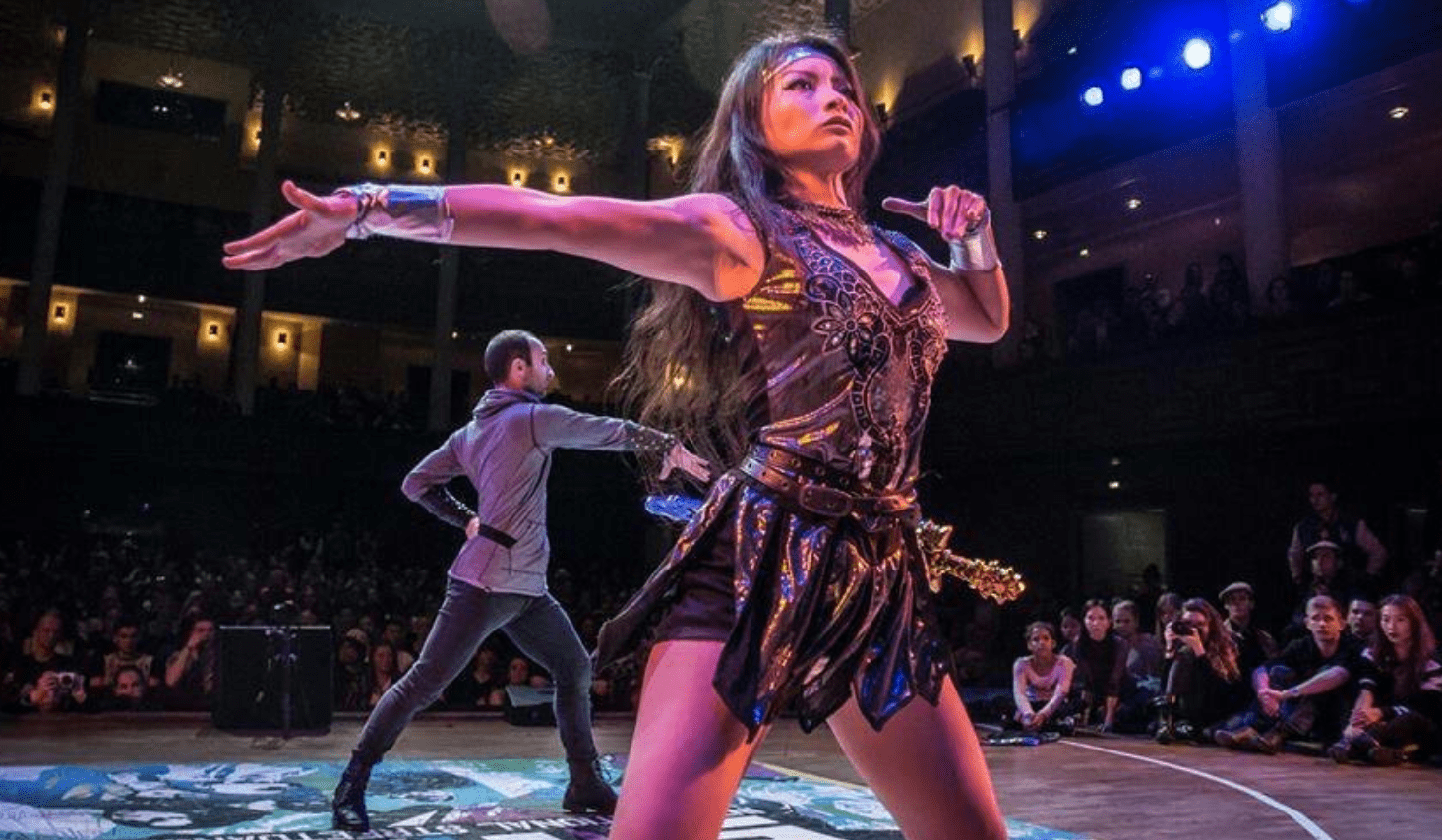

Koppi already had a background in other dance styles like hip-hop and popping. Intrigued by vogue, she began teaching herself techniques using YouTube videos of vogue battles. Koppi eventually joined House of Mizrahi, inspired by pioneering dancers and choreographers Andre Mizrahi and Leiomy Amazon, and dedicated her career to nurturing vogue and ballroom culture in Japan by teaching queer history, house systems, terminology, and ball etiquette.

Today, labelled as the Overall Legendary Mother of Mizrahi, Koppi is one of the highest-ranked ballroom participants in Japan, and is the teacher and mentor of many of Japan’s other top voguers and leaders. “I fell in love with voguing because it gave me a whole new persona,” she says. “I felt like I could be fully confident—like I’d never felt in my life before I started. I love the attitude [voguers] have, the atmosphere they create.”

As an ally, she began working with queer colleagues Showta Oricci and her son Kinshasa Mizrahi to connect Japan’s vogue with its LGBTQIA+ community, including performing. By 2010, Japan’s voguers mainly consisted of professional dancers and dance teams with no connection to ballroom or queerness. Texas native Kinshasa, a voguer and commentator who first joined ballroom in the United States, described their early attempts at holding balls in Japan. “Most of the people there were straight women. They didn’t know they could yell and shout when someone dipped. It was so quiet in those first balls. It was uphill work for me and Koppi in the early days,” Kinshasa tells us.

Ballroom etiquette – which is often argumentative and fiery – is also, somewhat, at odds with traditional Japanese social culture, which encourages people to maintain a polite and cool facade. Differences in subcultural expectations and attitudes has led to numerous culture clashes throughout the expansion of Japanese ballroom culture.

The ball boom: from 2011 to now

From 2011, when Koppi and Kinshasa first began holding balls, until 2022, interest in ballrooms gradually grew in Japan’s cities—particularly Tokyo, where Koppi, Kinshasa, and Legendary star Chise Ninja were based, and Osaka where voguers like Showta Oricci and Ku Marciano held events. Outside of teaching and organising balls, Koppi frequently performed in Shinjuku Ni-chōme (Tokyo’s Gay Town) at drag shows and other queer events, hoping to bring more and more queer people to her class. “Actually, I always wanted to have a ball in Ni-chōme, because it’s the centre of gay culture in Tokyo. But I didn’t really have connections with them, so I was struggling to increase the guests and contestants from the gay culture,” she tells GAY TIMES.

By the end of 2021, when I started taking classes with Koppi and attended my first ball (the “Anime Ball,” organised by Chise Ninja), Japan’s ballroom had grown to a healthy, lively crowd with chants, trophies, and overseas guest judges—a far cry from the early balls described by Kinshasa.

The greatest breakthrough for Japan’s ballroom came in 2022, when wonder kid Hiha Babylon (a son of Koppi’s through her kiki house, Pinklady), began organising the monthly Kiki Lounge (a kiki ball) in Ni-chōme’s most popular gay bars. The impact on the ballroom scene was instantaneous. Hiha’s Kiki Lounge brought cheek-to-jowl crowds that crammed around the runway like a mosh pit. Popular categories like OTA Runway and Female Figure Face attracted dozens of contestants, often spontaneous walk-ons. Voguing classes and workshops held by Hiha, Koppi, Chise, and Greek-born Elena 007 are regularly filled with fresh students.

Into the future of ballroom

In December 2022, Koppi organised the Discovery Ball in Shibuya aka the highest-level ballroom competition in Japan. It was also my debut as a member of the House of Mizrahi. I remember pacing and clutching my phone in the changing room, grinning from ear to ear.

The venue was packed full of people. Familiar faces from the Kiki Lounge, but also voguers and house leaders from all over Japan who had travelled to Tokyo to judge or compete. Koppi was almost brought to tears as she addressed the crowd, thanking them for coming.

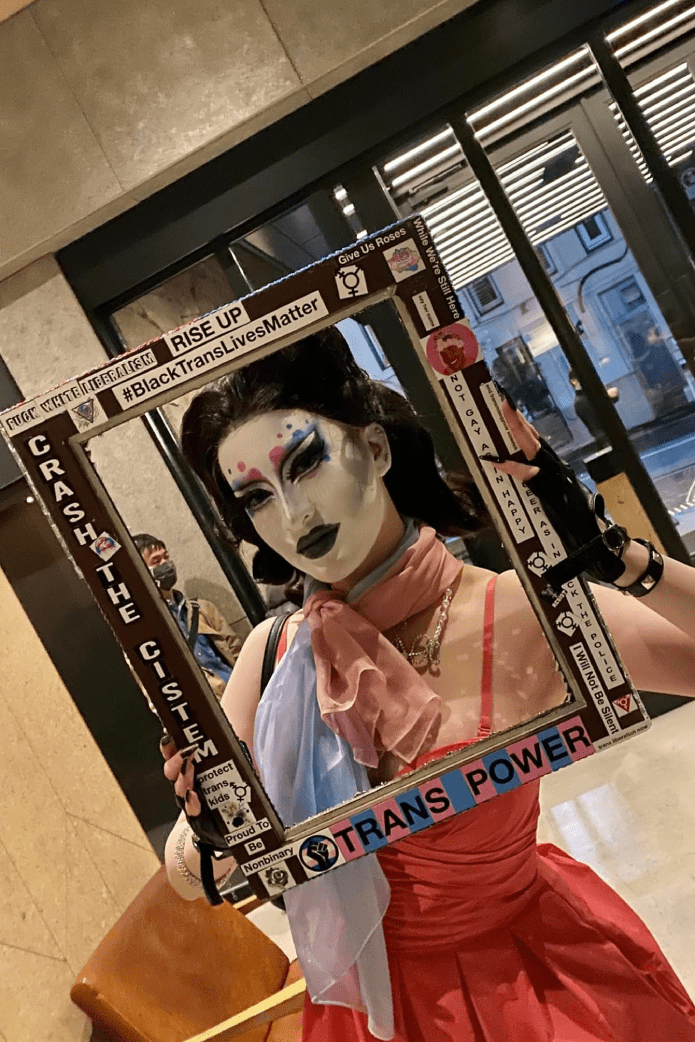

Japan’s ballroom, still young, is in a period of rapid growth and evolution. In just a few short years, I have seen it gather strength and velocity. In particular, I’ve been impressed by how the scene has adapted itself to be relevant to its local queer community, such as including drag queens like myself more heavily in its major and kiki houses and holding Drags Face categories in which we can compete. It is also a scene still open to innovate and welcome more diverse crowds of participants, taking cues from New York City icon Symba McQueen by implementing Gender Nonconforming (GNC) Face and Realness categories for nonbinary and nontraditional contenders, as well as spearheading a Lesbian Realness category to welcome more queer Assigned Female at Birth participants.

As one might expect for a subculture with a long and deep history, Japan’s ballroom leaders must balance respecting long-standing categories within the US ballroom system and experimenting with their own—a delicate process our leaders have excelled in. Japanese ballroom had a slow start in its early years, in terms of its existence as a queer space. But, it is exciting to see how the last ten years have transformed and accelerated its growth.

Today, entering a monthly kiki ball is like being hit with a wall of sound: chanting, cheering, and screaming. The crowd is full of familiar faces. The judges – stone-faced and terrifying – are my friends and my colleagues. It’s hard to chart the trajectory of Japan’s legendary new scene in the coming years, but the thriving scene fashioned here is unparalleled. And, in a matter of years, Japan’s ballroom community will be like any other.