In conversation with fellow queer black playwright Michael R. Jackson.

After it opened at the New York Theatre Workshop last December, Slave Play quickly found itself enveloped in controversy. Social media was alight with criticism, think pieces were unleashed, and a change.org petition calling for the production to be cancelled was launched. For playwright Jeremy O. Harris, the volume of reactions was unexpected.

“I thought the people who would have opinions on the play would be people who interacted with it in a theatrical space, but the majority of the people who have interacted with this play have only interacted with the title and some PR images that were found online,” he explained to us. “That was surprising to me, because I didn’t take into account that the internet would intersect with my world.”

In the aftermath of the show’s whirlwind run, Jeremy spoke to fellow queer black playwright Michael R. Jackson about the polarising nature of Slave Play, the biggest hurdles he’s faced as a creative in the world of theatre, and why he’s cautious of ‘normalising’ the queer black experience for a mainstream audience.

Michael: Were you surprised by the response Slave Play got from a 2018 audience?

Jeremy: It had the response that I was expecting, in some ways, because it was both really loved and really despised at the same time. It was a very polarising event. It sold out the entire run which is really cool, and it got extended. I didn’t do calculations on a lot of factors, and I think I took for granted the fact that whenever I talked to black people in my social circle, they had known me forever, so they knew my humour and they knew the rigour with which I interact with the world, and when I told those people I was working on Slave Play they were like, ‘That sounds amazing’, and this was foolhardy of me, but I didn’t realise that doing a play called Slave Play after having a bunch of white magazines saying it was brilliant would be difficult and triggering for a lot of black people who don’t know me well enough to give me the benefit of the doubt. And moreover, I didn’t realise there was a possibility that my play could go viral on the internet. I thought the people who would have opinions on the play would be people who interacted with it in a theatrical space, but the majority of the people who have interacted with this play have only interacted with the title and some PR images that were found online, and that was surprising to me, because I didn’t take into account that the internet would intersect with my world.

Michael: Would you say that’s the biggest hurdle you’ve encountered so far?

Jeremy: For me, this isn’t really a hurdle. It’s been a weird thing to navigate because I didn’t expect it, but it’s actually been instructive more than anything. It’s taught me a lot about what it means to work in a space of provocation and abstraction, and it’s also taught me a lot about how, even though we’ve made a lot of progress in representation, as a community there’s still a lot of conversations we haven’t gotten a chance to have about what our platform in this moment means as black people, as black queer people, and as theatre artists. I think what I’ve learned from this experience is that this is a great opportunity – as a person who doesn’t come from wealth, and who comes from two oppressed communities – to talk about what it means to be working in a community where my product is a luxury item for rich people. Generally, it’s rich white people who are consuming theatre, so what does that mean for both of my communities when I’m working in a space where there’s potential for profit from a lot of different pockets of what we do? Like, what are my responsibilities working in that space? And I would say my bi est hurdle has been navigating the role of institution, and learning how to navigate my natural distrust of institutions while recognising the fact that if I want my work to have a platform, and if I want to eat, on a very real level, I can’t be someone who only does work I self- produce, I have to engage with institutions. I think that’s the biggest hurdle psychologically for me.

Michael: Your piece Daddy is opening with New Group and The Vineyard, what can we expect from that?

Jeremy: I think what excites me this season is that we’re getting to see a lot of different work especially by black writers, and I’m just getting really excited about what Slave Play and Daddy can say in that landscape about the world as I see it. I’m such an art freak, in both the sense that that play is directly about art, and the sense that both Slave Play and Daddy are dripping in art world references. I think what people are going to see is that the space I’m carving out for myself outside the season is not specifically one where I’m gonna be able to take the crown as the person who is talking about black sexuality in a scary and interesting way, but I think what people will see is, ‘Oh, Jeremy has carved out a space for the person who’s obsessed with the art world’, specifically the history of the black art world. I’ve been learning how to adapt that, and queer theory, into my plays, and I think that’s fun. I’m excited about getting to do that, and I’m excited that I’ve been afforded the chances to let my love of spectacle be put on display in both of those plays, by three different theatre companies. One of the great things is they’ve been allowing me a lot of autonomy when engaging with my spectacle.

Michael: That’s awesome. We’re very excited about Alan Cumming starring in Daddy. Why was he an important casting choice for you?

Jeremy: Well I think that Alan is one of the great actors of this generation, obviously, but also when you want to have a play with a pool on stage, and you’ve never had a play produced before, it’s very difficult unless you have someone that a producing organisation feels can be a draw for an audience. So when Alan said he wanted to be in the play, it was like a Dod send, because when people say they want a celebrity to be in the play, I was thinking of the worst version of it, right? It’s a play called Daddy about an inter-generational, interracial relationship between an artist and an art collector, and they’re like, ‘We just need a celebrity, period.’ I’m thinking like, this theatre company’s gonna go to Ray Romano and offer him the role or something. That was my fear, because we see that a lot. So I made a real big rule that I wasn’t gonna have a celebrity in this play, I would rather wait until I can be a playwright celebrity and just get a play produced on the merits of my name than invite someone to play this role who’s not a queer or gay-identifying actor, or who is just not right for the role. When Alan said he wanted to do it, I was like, ‘Well Alan is one of the great actors, and he’s a queer man, I need him’, and luckily he felt like he needed to be in this play too. So now we have this really phenomenal inter-generational cast, and the energy Alan has is so alive, and he’s such a giving actor and I think everyone in our cast is really giving.

Michael: How do you juggle working on two plays and being a third-year student at Yale’s School of Drama?

Jeremy: You don’t sleep! No, you sleep, but you put things off. You just figure it out, right? I’ve said this before but I’ll say it again: I don’t think what I do is hard. I don’t know if you feel the same way. It’s emotionally draining, but it’s not actually difficult. A big chunk of my time is having coffees with people, and talking about ideas, and then I think about how when my mother was my age she was in the middle of getting a divorce, she had two kids, she was working three jobs to put them through private school, and I don’t have any kids, and I definitely haven’t had a relationship long enough to feel like I’ve even had an emotional divorce. So I think that I’m in a pretty good spot, if the biggest things I’m struggling with are plays and grad school for theatre. Like, those things are difficult independently and especially thrown together, but none of those things are putting my body in such dire straits.

Michael: How do we bring narratives of queer people of colour into the mainstream without it being seen as ‘other’?

Jeremy: For me, I don’t know that I want it to be seen as not ‘other’ right now. I mean, I think normalising our experience is something that frustrates me. I was having dinner with someone the other night, and we were wondering, ‘Would Moonlight have been one of the most popular queer movies in the black community if Chiron had actually kissed Kevin?’ I’d like to imagine that it would be, but I do think it would have almost othered the movie even more, othered it into a space that would have made it deeply comfortable for me, but made it more uncomfortable for people in the mainstream. Like, if they’d made out, it would have othered the movie for my mom – well, maybe not so much my mom, because my mom has seen me kiss people, but definitely my mom’s friends, who felt the movie they saw was deeply universal and relatable to their lives. In a lot of ways, there’s a beauty and a difficulty in making something that can be universal, but I think what excites me a lot is not being universal, and making someone have to take me in my othered space for who and what I am. I think that takes a huge leap. And there are white queer filmmakers who have made work that excites me because it stands in its otherness, and I think those have always been my totems of what I want to do, and what I aspire towards. So I’m looking at John Waters, Bruce LaBruce in some ways, these queerdos who are like, ‘If you want it, you have to take all of it’. Acceptance isn’t just accepting the palatable parts of me, it’s accepting the part that’s in the steam room with the poppers as well.

More information on Jeremy O’Harris can be found here.

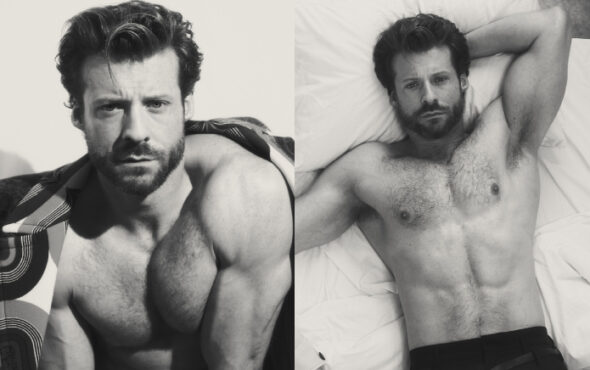

Photography David Needleman

Words Daniel Megarry

Grooming Janice Kinjo

Sweater LOEWE