When the US women’s national soccer team (USWNT) crashed out of this year’s Women’s World Cup following the necessary dramatics of a dramatic penalty shootout, few would’ve anticipated it. They’d entered the tournament – this edition hosted by Australia and New Zealand – as champs, boasting over a dozen gold medals and cups in Olympic and The Confederation of North, Central America and Caribbean Association Football (CONCACAF) competitions. 2019 saw the USWNT pick up their record fourth World Cup title, while simultaneously tugging at the heartstrings of queer and lesbian women around the world because there were no two ways about it: queers were front and centre.

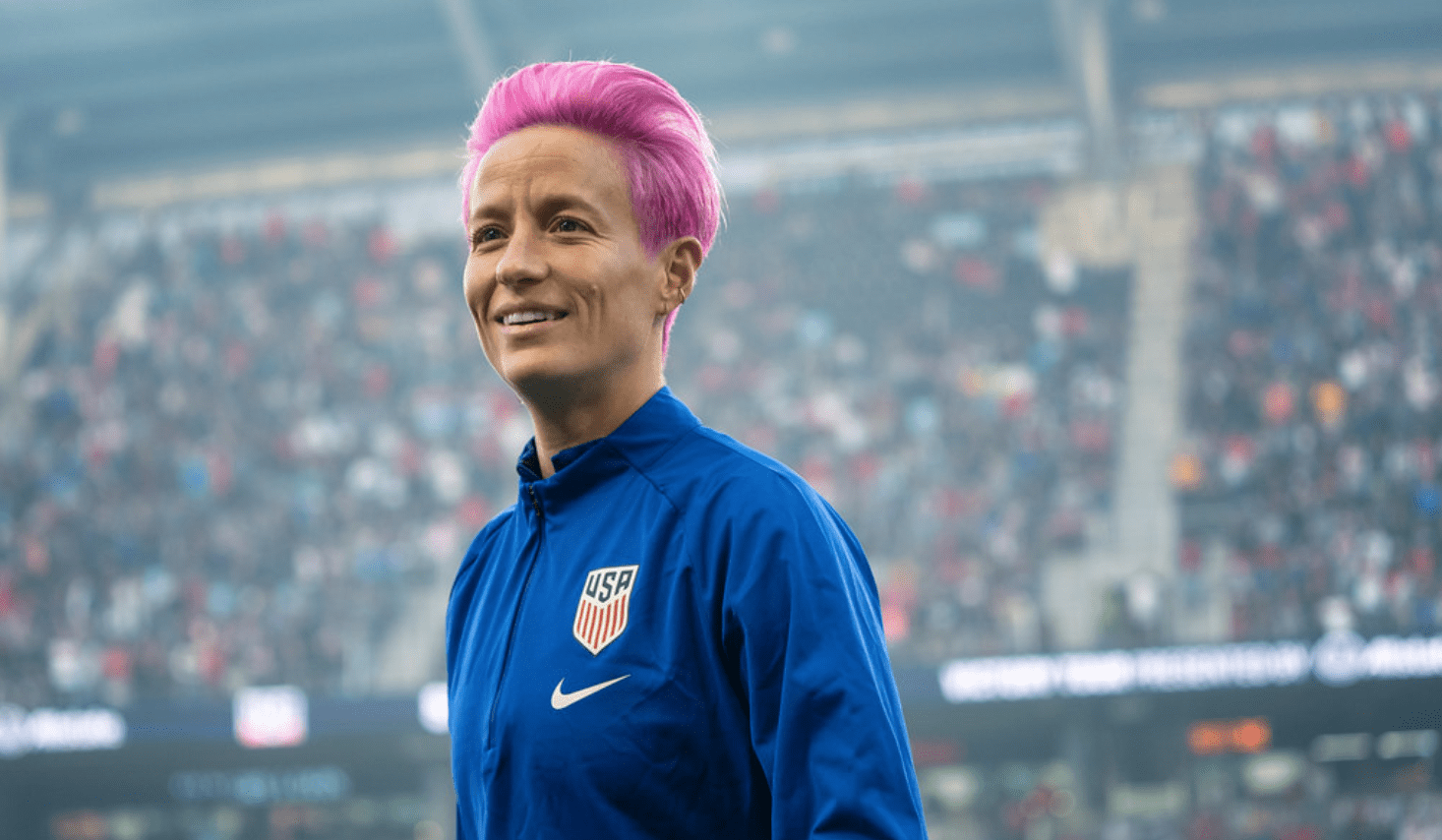

Decorated player and vocal local lesbian, Megan Rapinoe co-captained a winning squad which featured a number of out, queer players including Tierna Davison, Ali Krieger and Ashlyn Harris – with the latter two being engaged, and now married, to each other. The USWNT was guided to success by another out lesbian, head coach Jill Ellis. ‘Lesbians won the Women’s World Cup’, declared Buzzfeed News’ Shannon Keating while writer Jill Gutowitz tried to put words to why queer women were obsessed with the US team: “They’re heralded as such by queer women and straight sports fans alike. Some, like Rapinoe, have even been elevated to that coveted “athletic superstar” status. An out, conspicuously lesbian athletic superstar? That’s monumental.” Perhaps what is even more momentous is that the clamour around the 2019 US squad builds upon the queers who came before them, walking out on freshly trimmed grass in their countries’ colours decades ago.

Football has long been coded into the Brazillian cultural identity with the nation earning a reputation for its flair-filled ginga style of play: dribbling, juggling and no-look passes which combine samba dance and the martial art of Capoeira, which can be traced back to 16th-century Angolan traditions. However, while Brazil’s men’s football team would go on to make a name for itself on the global stage and clinch two World Cup titles in 1958 and 1962, the women’s game had been prohibited in Brazil since 1941.

Under the dictatorial leadership of President Getúlio Vargas, it was believed that women playing sports went against their ‘nature’, stifling the women’s teams that had become established across the country, with at least 40 in Rio alone. Though the ban would be lifted in 1979, football had become synonymous with virile masculinity, with women eschewing the sport for fear of being seen as masculine or, worse yet, “big shoes” – a derogatory term for lesbians. Yet, against this backdrop, a number of gifted queer Brazillian players would emerge.

Born just a year before the ban was lifted, Miraildes Maciel Mota – nicknamed Formiga – would come off the bench for Brazil as a 17-year-old at the second-ever edition of the Women’s World Cup in 1995. A year later, she’d meet her partner, Erica Jesus, but a likely combination of an athlete’s schedule, teenagers navigating love and lust, and enduring oppressive legislature and attitudes put things to an end.

Establishing herself as a focal part of Brazil’s midfield, Formiga would earn her nickname – which translates as ‘ant’ in Portuguese – for her selfless style of play, reminding fellow players of how colonies of ants work together. Her impact is no doubt why she holds the record for appearing at seven different Women’s World Cup tournaments – and the only player of any gender to play in seven World Cups and seven Olympic Games. At 41, Formiga would become the oldest player to appear at a Women’s World Cup as part of Brazil’s 2019 squad. Though they were eventually knocked out by France, perhaps the bitter defeat and the ever-elusive World Cup trophy were softened by Formiga and Erica reconnecting in 2017, and tying the knot in January of this year. Reflecting on her career in a podcast, the legendary figure pinpoints the difficulties she faced with ease: “I had to work hard to conquer my space and prove who I was. Not only as a player but also as Miraildes Maciel Mota: woman, Black, Northeast, lesbian. And, above all, as a person who never thought of doing anything other than playing football.”

Across her tenure, Formiga shared the Brazillian dressing room with other lesbian footballing talents, from the prolific striker Cristiane and shot-stopper Bárbara to the legendary Marta Vieira da Silva. Simply known as Marta, she is easily the country’s most well-known woman footballer. Considered by some as the greatest of all time, a 17-year-old Marta burst onto the international scene at the 2003 World Cup held in the United States, aiding the team to the quarter-finals before they succumbed to Sweden. 2007 would see Marta make her mark. While Brazil would fall short, losing 2-0 to Germany in the final, the burgeoning star walked away a winner of both the Golden Ball, for her individual performance, and the Golden Boot as the competition’s top scorer, having netted seven goals.

Like her former teammate Formiga, she would rack up her own records, including becoming the first footballer of any gender to score at five different World Cups and receiving the Best FIFA Women’s Player award six times. But, for many Marta fans, the impact of the rainha do futebol – queen of football – crosses beyond the footballing world. After Marta shared the news of her engagement to her partner and Orlando Pride teammate, Toni Pressley, on Instagram, it served as a significant reference point for Brazilian queer communities. “Being LGBT in Brazil is an act of courage. LGBT people like us are not safe on the streets, like Marta is not safe, simply for being LGBT,” explains Julia Santana, a council member for first division club EC Bahia. In the same year that Marta led her to France for the 2019 World Cup, a report by campaign group Grupo Gay da Bahia would find that 297 LGBTQIA+ individuals were murdered in homophobic and/or transphobic attacks, with a further 32 people dying by suicide.

Fame, ability, wealth and opportunities abroad, to a degree, insulate queer stars like Marta from the abject hostilities faced by the most marginalised. Even so, the real-life risk carried by out and queer players, a perceived threat to the nuclear family and heteronormative order, remains indelible. It’s why South Africa’s Eudy Simelane threw herself into advocacy work, including carrying out voluntary work with people living with HIV – she knew what it was to exist in the margins.

Born in 1977 and widely referred to as one of the first women to live openly as a lesbian in her township of Kwa-Thema, the left-footed midfielder played for her local team, Springs Home Sweepers F.C., as well as the South African national team – the Banyana Banyana. Though her football aspirations would not see Simelane or South Africa feature at the World Cup in her lifetime, the beautiful game had long consumed her – she coached local youth teams and hoped to one day qualify as the country’s first woman referee. Having established herself as a key local activist, the news that Simelane had been sexually assaulted and murdered in April 2008 sent shockwaves through local and global communities. Despite South Africa’s emerging status as a trailblazing African nation where the rights of LGBTQIA+ people were legally enshrined, the murders of the local star and countless other conspicuous lesbians underscored a bleak reality. Entrenched societal values were more attractive than new legislative jargon – values which included ‘correcting’ queer women by any means necessary.

Though this year’s World Cup is the ninth edition to take place, it remains a tournament full of firsts. The first to be hosted by more than one nation, the first to see the number of participating countries increased from 24 to 32, the first to feature a footballer, Morocco’s Nouhaila Benzina, wearing hijab at a senior-level global tournament, and the first to see an out trans or non-binary footballer in the form of Canadian midfielder Quinn. They are one of at least 96 publicly out footballers in this year’s competition, meaning that over 13% of all athletes competing are queer.

Much like the wider sphere of women’s football, queer players are overrepresented at the World Cup. Tenderly dedicating goals to partners, like Colombia’s Linda Caicedo’s heart-shaped gesture to her girlfriend, and clambering up to the stands for a victory-sealing smooch in front of flashing cameras, as Alba Redondo did after Spain’s win over Zambia, have become common-place scenes. However, a willingness to live openly and intentionally during the world’s most prestigious tournament is taken by some as an invitation to pry and probe.

“In Morocco, it’s illegal to have a gay relationship,” began a BBC reporter during a post-match media conference in Melbourne with Moroccan team captain, Ghizlane Chebbak, and coach, Reynald Pedros. “Do you have any gay players in your squad, and what’s life like for them in Morocco?” Chebbak’s face, which flicks from marked discomfort to incredulous laughter in seconds, isn’t enough to deter the unnamed journalist. “No, it’s not political, it’s about people,” the journalist insisted after a FIFA official requested that questions stick to football. “Please let her answer the question.” His only response would be Chebback’s disbelieving shake of the head and her awkwardly fixed grin before the relief of the next journalist’s question.

Many have astutely dissected the interaction – the entitled invasiveness, safeguarding of potentially endangered players, the answer already laced in the question, and the slim likelihood that such a question would be posed at a men’s World Cup to name a few. What is most striking to me, however, how this exchange epitomises the dichotomies of queerness at the highest level of women’s football. Asking a deliberately provocative question, despite having already cited the danger, towards a team whose country religion is Islam, carrying the potential risks of demonising both the religion and a nation that sits beyond the West. Having access to a wealth of players who speak openly about their sexuality or gender identity, yet seeking out those who have not. One in eight players being queer, including team captains Daniela Montoya (Colombia), Sam Kerr (Australia) and Katie McCabe (Ireland), yet the rather innocuous rainbow armbands have been banned and replaced with eight FIFA-sanctioned armbands with deliberately vague phrases like ‘Unite for Peace’ and ‘Football is joy, peace, love, hope & passion’.

The contradictions are built into a sporting industry that has long-stifled women and LGBTQ+ players, let alone those who are both. From the governing bodies and federations to the media pack, to the fans and the wider public, the expectations and demands on queer footballers feel increasingly stifling, while offering little in the way of meaningful support and resources – codified anti-homophobic protocols and charters upheld by FIFA, working with queer players’ unions to ensure there are support systems in place for them, established pathways for up and coming queer and trans players. Stars, like Formingo, Marta and other names we’re yet to learn or may never know, have risen to the highest level of women’s international football in spite of the consuming violence that sporting bodies ignore; the same violence that stole Simelane’s future.

Beneath the meme-able moments and the reliable lesbian drama lies a sobering history – and enduring reality – of queer subjugation: an issue that will only become more urgent with future World Cup editions as more lesbian and queer players claim their places in the illustrious tournament that many of them had once only dreamed of.