Everyone knows that Wikipedia can’t be trusted: you’re taught from an early age that if you want to find something out you must use a reliable source, one with expertise, a knowledge and understanding much deeper than yours, or that of a potentially edited Wikipedia page. In a climate polluted by fake news it’s increasingly become our responsibility to plunder the authenticity of our sources, of the ways we receive the information, the facts, the stories.

For some reason, however, it seems as though powerful storytellers — the ones who sit in air conditioned board rooms lining the Sunset Strip — have a blindspot when it comes to telling the stories that live inside minority experiences. Over and over again tales from within the LGBTQ community are told by actors, and teams, who have never even touched their own butt holes, let alone undergone a lifetime of actually living the often painful experience they have the “empathy” and “bravery” to play. A name check here for Call Me By Your Name, God’s Own Country, Love, Simon, Anything, Dallas Buyers Club, The Danish Girl. The list really does go on (and on)… but you get the gist.

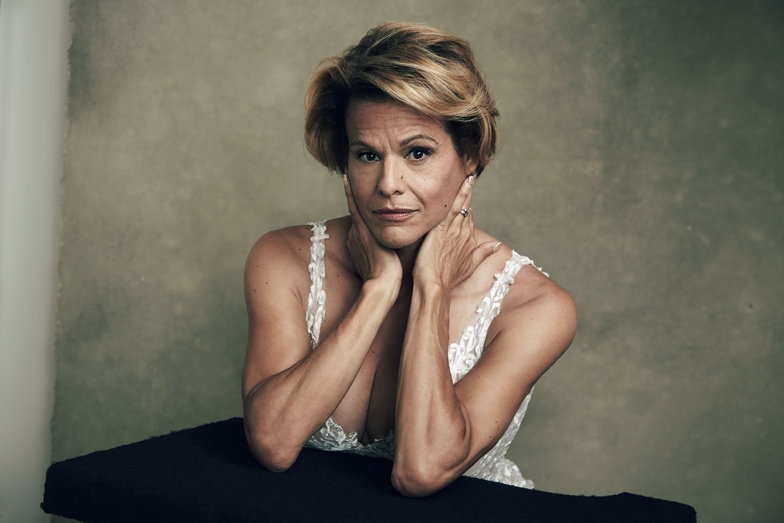

It seems as though when it comes to telling minority stories, any old Wikipedia page will do. And that’s where these women come in. Meet four of the stars of Transparent: Alexandra Billings, Trace Lysette, Alexandra Grey, and Rain Valdez. Across the four, soon to be five, seasons of the groundbreaking show which saw trans storylines spotlighted in nuanced ways like never before, these women played varying roles, offering up depictions of different parts of the trans experience. It was the first show of its kind: where they hired trans talent both in front of and behind the camera, in the writers room and on set.

Aaron Jay Young / Gay Times

“They were brave enough and accessible enough to listen and hear what was happening,” Rain Valdez explains when I ask if she thinks Transparent got it right. “I think they did their best, based on what they were learning through the process. I think Transparent became what it is and became very authentic and became a beacon of hope for what creating content could look like, and what allyship could look like.”

“Transparent was my first major acting role, and got the most acclaim to date, but it was also my smallest role to date,” Alexandra Grey adds. “I wasn’t on that set too much, but I remember feeling the love early on, and in comparison to doing other TV work, Transparent was a positive experience, which is the only way it should be.”

But of course, the show had it’s problems too: the lead role given to Jeffrey Tambour, who has now been ejected from the cast after allegations of sexual harassment, caused rightful outcry way back when the casting was announced because, yet again, a cis male actor was going to lead the depiction of transness on screen. Thereafter, the show’s creator, Jill Soloway, committed to hiring as much trans talent as they could. But was that enough to really change Hollywood?

“Anytime you’re employing trans actors you’re on the right track,” Trace Lysette, who played the brilliant Shea, tells. “But I haven’t seen my story yet. I haven’t seen a working class, urban trans woman from New York City — I haven’t seen my journey. I think it’s a really crucial moment in trans Hollywood right now, and we have to take the reigns and have to create our own opportunities because waiting around for cis heteronormative predominantly white Hollywood to give us a chance… well, we are all a bit tired of taking baby steps.”

While Transparent represented perhaps the biggest of these baby steps, all of these women are still focussing on making their own opportunities, their own self-authored work that actually speaks truth to power and centres their experience without the harmful gaze of what cisgender storytellers assume a trans story looks like.

“I just would like to see trans people centred in whatever story,” Trace continues, “and not only our struggle, but also our brilliance, and community, and the happy ending so to speak. I think oftentimes we don’t get to see the day-to-day and the joy that we experience and I think that the world needs to see what it looks like when we are happy and when we are loved.”

The representation conversation is one which has arguably come a long way — for the most part (save for Ab Fab and Ghost in the Shell) we don’t have white actors playing people of colour like in the twenties and thirties; we don’t have male actors playing women like in Shakespearean times. So why do we still have cisgender and heterosexual folk sopping up all the roles for trans folk, non-binary folk and homosexuals? Surely an actor’s job is to play roles across the board? Surely a storyteller should mine the hurtful and harmful experiences inflicted on communities to show the world what it’s really like?

But the problem is, it’s never what it’s like. The problem is it’s a mere projection of what a minority experience looks like through a normative, and often white, lens. The problem is that while well-known cisgender actors step ignorantly into trans roles a harmful myth is perpetuated that the trans character on screen is really just a cis body, because the moment they step out of the role the world sees the actor as cis once again. The problem is, it makes transness look like a ‘temporary state’. The problem is, it sets a normative beauty standard that trans people should look exactly like cis people. The problem is that harmful depictions of trans and non-binary folk, of people like us, is that it never solves the violence — it only portrays our bodies as sites for it, because we only tell stories about it. The problem is, cis-normative culture thinks our lives are only violence, trauma, pain. But they’re not.

“I think oftentimes we don’t get to see the day-to-day and the joy that we experience and I think that the world needs to see what it looks like when we are happy and when we are loved,” is Trace’s answer to this. “It’s so important for the world to see all that we are and not just their tiny scope of what they think that they know about us because these myths are perpetuated over and over by cis heteronormative people, and have been for decades.”

And these women are putting their talent behind their words. When I ask them what they’re all working on personally, they reveal that they’re telling a range of stories which highlight unseen aspects of the trans experience. Trace has just been cast as the lead in Colors of Ava, in which Rain also features and will be co-producer, which is described as a love story. Alexandra Grey has just acted in, produced, written and directed her own film The Blue Sky which is about falling in, and negotiating, love as a black trans woman.

There’s a common thread between the stories these women are telling: they’re all variations on the theme of the love story. And think about it — have we ever really seen a trans love story told, and told well? All there is is that terrible one where Eddie Redmayne spends three hours blushing in a corset.

“I always related to and gravitated towards watching rom coms growing up because as a young trans person life is already hard, so rom coms kind of gave me that escape and that fantasy of being able to find love and being able to find fun in life,” tells Rain when asked about why she’s so drawn to telling love stories. “So, as a young girl wanting to grow up as a woman, I always saw myself in Sandra Bullock or in Julia Roberts. ” I ask the same question to Alexandra Grey.

“I think it’s important — you know we talk about all this casting controversy, Scarlett Johansson,” she adds. “But what people fail to realise is that none of these storylines ever centre around minorities, and African Americans, and what it’s like to be a black trans person in America or in the world. I want to do that, so that I can be reflection to those little brown trans girls and trans boys, who don’t know what it’s like, and also for those people in African American communities who never deal with the LGBTQ community. It’s time for us to do better — it’s time for us to talk about diversity across the board. And that was really important to me in making my film The Blue Sky. I wanted to depict what that was like as a black trans woman falling in love with a black man.”

“So we need to not only focus on who gets to tell the stories, but also what stories are told?” I ask Alexandra. “Right. I’ve done about eight guest stars on TV: I’ve played crackhead twice, a prostitute, a murderer, a drug addict, a cancer patient. I’m very grateful for that, but none of them have been positive representations of the trans experience. And that’s what my film is going to show you. It’s going to show you the trans woman college student who’s very smart and loves music and and works a job and lives a normal life. We don’t often see that. Especially when our trans narrative is centred around white trans people — it’s only one representation. When the average life expectancy for black trans women is 35, and black trans women get murdered at really high rates all the time in this country, I think it’s about time for us to see ourselves reflected: that might open people’s hearts and minds a little bit.”

Violence begets violence, and when so many people’s only experience of transness is seeing it badly portrayed on the cinema screen, that violence replicates in real life. We need to be seeing stories about trans folk who love, who deserve to be kissed from head to toe, just like anyone else.

“Yes,” says Rain, “because these stories decide who gets to be loved. It tells the world boy meets girl, girl meets boy, you know, and at the end I’m like ‘who gets to be the one gets to succeed in love?’ Hollywood has such a huge influence in the world in terms of how culture is shaped and how society is shaped, and it’s no wonder we’re constantly being otherised and trans women are being killed by the number every year. It’s no wonder trans people are being kicked out of their homes or not being able to get the jobs that they want or have hard time dating.”

There’s no doubt that these four amazing women know exactly how to tell the stories, and what stories need to be told to both represent the trans experience and make it safer and happier in reality. But the final question must be about how we achieve this. Time magazine decreed we were at the trans tipping point, some two years ago now, but are we really?

“I hope so,” Trace laughs. “But I think this change starts by intentional allyship and what I mean by that is: people with access, usually cis folk in Hollywood, offering us the shot or the opportunity to be involved with projects that are for us and about us. And sometimes that means that they have to step aside a little bit because a lot of us have been in this industry a while but we are hitting this kind of glass ceiling. It’s about access, it’s about people and access. The perfect example would be Ryan Murphy taking Janet Mock under his wing and allowing her to write and direct on Pose. I also think sibling-hood between trans folk in the Hollywood industry is really important because hopefully those of us who have a foot in the door are going to work together for a very long time. And I think that once we all get to collaborate and share our brilliance the world will be able to see our authentic narratives. So I’m looking forward to that.”

“I’m not asking to be in a room with Viola Davis and Halle Berry,” Alexandra Grey concludes, “I am asking to be considered for a role that you’re casting for an African American woman, whether cis or trans, that you give me that opportunity to come in and show you what I can do. Viola Davis said it best: ‘If you’re committed to inclusivity let it cost you something.’ I say to those producers and writers and execs: I say take that chance — they have the power to make history. Take that chance because there’s never been an award for acting by a trans person in anything. Start taking those chances on us, be a part of the change. Because we might win an oscar, and then you’ll have made a whole new Scarlett Johansson.”