From ‘conversion therapy’ to the Gender Recognition Act, the British media has long picked apart issues impacting the lives of transgender and non-binary individuals with a sharpened knife.

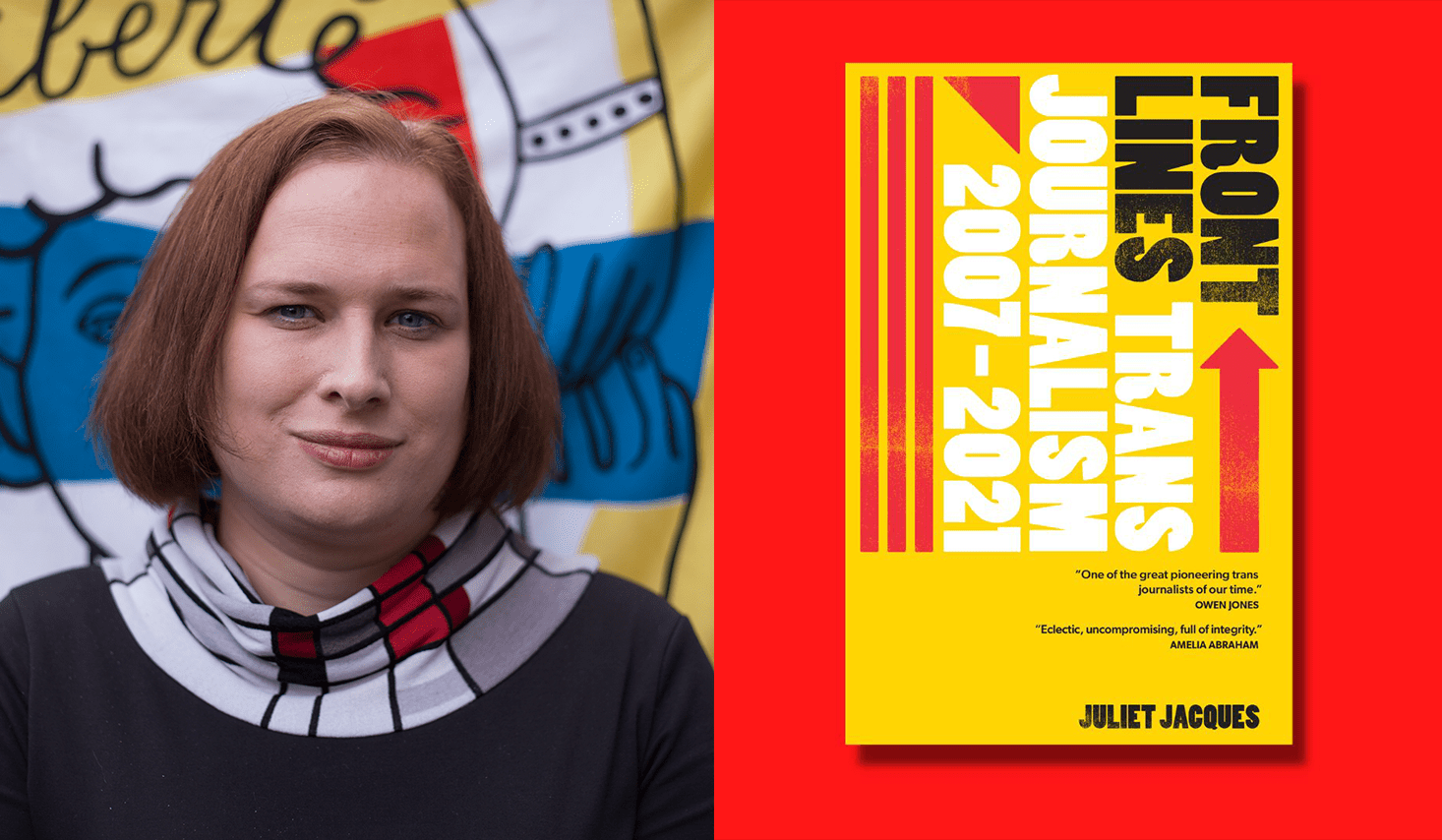

As one of the UK’s most pioneering transgender writers, esteemed journalist Juliet Jacques has been on the front lines of British journalism for over a decade and has used her platform to fend off attacks and normalise trans lives.

Being one of the first to write widely about the trans experience in many spheres – from the political to the cultural – Jacques’ new book Front Lines chronicles her published writing from 2007 to 2021, a period of much turbulence and change for trans coverage in the British media.

Nicknamed ‘the Transgender Journalist’ during a CNN panel in 2011, GAY TIMES spoke to Jacques about her journey through the British media and what the often problematic, hateful and right-wing coverage means for trans liberation in years to come.

In Front Lines you discuss how you were nicknamed ‘the Transgender Journalist’ – looking back did you feel a real sense of pressure on your shoulders?

I mean, there were other writers doing similar things at the same time. So I wasn’t working in total isolation, I think that’s important to say. I did end up thinking a lot about this kind of burden of representation. Because, I could never claim to be representing anyone else other than myself. But also, anything I did in these big spaces where people are paying attention, The Guardian, the New Statesman, and places like that, have to be careful not to misrepresent anybody, and not to paint “the community” in a bad light, whilst also trying to maintain honesty and journalistic integrity. I think there’s a difference between advocating a cause and kind of propagandising and one tries to keep it to the former rather than the latter as much as possible. So there were lots of difficult lines to walk. And I think that does come out in the book, and in the introduction that reflects on it. I mean, at times, I did feel kind of out on a limb.

In your book, you refer to the anti-trans media as ‘they’. How do you think this ‘they’ has transformed from the beginning of your career to today?

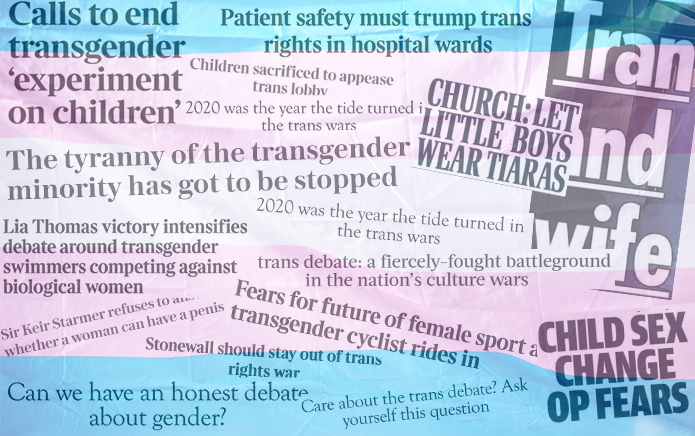

The reason why I use this sort of collective ‘they’, it’s not just to annoy them by using a kind of non-gendered pronoun, although it does, it’s because there’s a more explicit editorial position now than there was 12 years ago. What I was trying to do in the early 2010s, I think, was sort of exploit a kind of ideological function of the kind of neoliberalism that we live in, which is this idea that basically anything was justifiable if it sort of turned a profit, or people were interested in it. So I said I could sort of demonstrate to these editors. “The public” were actually interested in trans issues and would read about it, would engage with it, then we would be given more kind of space and maybe a fairer hearing. I often think about that Time Magazine, that transgender tipping point article, I think it was May 2014, and the idea that trans rights and visibility had reached a sort of tipping point where they could no longer be ignored or rolled back. And obviously, that’s an American publication, but I think there’s always been quite a lot of cultural interplay between the British and American public sphere. And I think the internet has obviously narrowed that gap a lot more. I think a lot of our enemies took that tipping point as a sort of direct challenge. I think there was a much more conscious ideological pushing back, being like, ‘Well, we don’t care if there’s an audience for this or not, we do not want there to be.’ One of the mistakes I made in my approach to this was giving these people way too much benefit of the doubt, inconsiderable doubt really. Certainly, there were a lot of people on Twitter telling me I shouldn’t be so forgiving of people or trusting of people. In hindsight, I think they were right. I really did not expect certain people in certain publications to take such an explicitly anti-trans position, often under the guise of debate, not to take it but to maintain it even when it was obvious that this anti-trans position had become a very big recruitment tool for the resurgent global far right.

You mention the legislative attacks on trans and non-binary people in Front Lines that are currently playing out in the UK and abroad. Can you speak to what some of those are?

‘Conversion therapy’ is an interesting example of what I’m talking about. If there hadn’t been so much pressure from groups like the LGB Alliance to make sure that trans people were not included in the ‘conversion therapy’ ban then that probably would have just passed by now. As it stands, there’s evidence coming out of the Liz Truss campaign, via Iain Duncan Smith, talking about rejecting the ‘conversion therapy’ ban entirely. So you see the dangers of that kind of divide and rule and what it intends to mean is that there’s no rights for anybody. In terms of other things, there’s the pretty terrifying precedent of Viktor Orban’s Hungary rescinding gender recognition retroactively in 2020. Given how much of an admirer of the Orban government, certain people in this country are, that’s particularly worrying, obviously. There was Liz Truss floating proposals in 2020 to basically ban trans and non-binary people from using any public service that was for their gender of choice, which is also pretty terrifying. That didn’t go through, partly because there was a big protest movement against it. In America, the Trump government basically attempted to just mandate trans people out of existence entirely, using trans people in the military as a kind of wedge in the wake of the Chelsea Manning case. In Poland, gender studies are being banned from university, in Brazil there was a very big public campaign against Judith Butler personally, as being seen as like the high theorist of gender identity and gender theory. I mean, there are plenty of other examples as well in other countries around the world of sort of broader anti-LGBT legislation in Russia, in Kyrgyzstan, Turkey, etc. And I think something that’s really important to think about is that, if our right wing politicians say they plan to do these things, we have to prepare for them to at least try and do them and resist that.

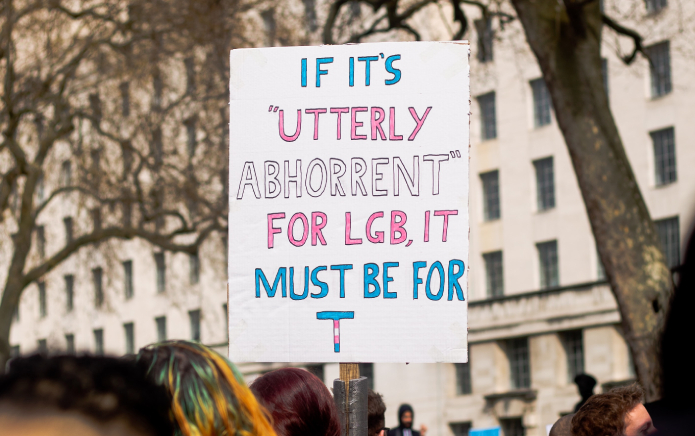

It looks pretty likely that there’s going to be an attempt to reintroduce some version of Section 28. Whoever wins the Tory leadership, I think that’s quite likely. It’s easy to look at that now and say, ‘Well, you could never make Section 28 work now because of the internet.’ No, you probably couldn’t, but I think relying on that sort of precepts to save us from legislative attacks is very complacent. There’s going to need to be all sorts of resistance, legally. I think it’s going to be very important. We’re going to have to gear up for some big legal battles in the media as much as possible. Again, we might have to, as we did in the early 2010s, get our hands dirty and put our cases across in places that are hostile to us. I don’t think our strategy of trying to use contributing to those spaces to make them more meaningful to us hasn’t worked, but I don’t think the strategy of just leaving them to the opposition is a particularly good one, either. So we’re going to have to work there. We’re going to have to work in our own spaces and in the streets. We are going to have to be out demonstrating and showing our numbers. One of the positive consequences of the work that lots of us did in the media in 2010s was to show how many trans and non-binary people they are. And by extension, how loved we are by our friends and family. We are gonna have to mobilise those numbers. Even then it may not be enough, but we owe it to ourselves and to future generations to try.

In the book, you mention the characterisation of trans coverage being labelled a ‘debate’. GAY TIMES recently did a survey where 90% of our readers said that using this language is harmful. Just for those who can’t wrap their heads around why trans rights shouldn’t be debated, can you speak to why this framing is just so bad?

In terms of debate framing, you’re talking about people’s self chosen identities. And as a consequence of that kind, their right to exist as the people we are and feel ourselves to be. So the debate framing is just a sort of immediate way of undermining that. What it’s designed to do is freeze any conversation about trans issues on what’s basically an unwinnable argument. This debate basically comes down to trans people saying, ‘These are our identities, this is who we are,’ and gender critical people or transphobes saying, ‘No, they’re not. No, it isn’t.’ And there’s not a debate there, a debate implies that there might be some sort of midpoint between those positions that can be reached, and there isn’t. Or something that could be built on whatever conclusion comes out of that debate, which can’t. It’s not a debate, it’s a form of attack. It’s designed to stop us focusing our energy on talking about healthcare, housing or employment, social relations or any of these other issues that are particularly difficult for trans and non-binary people to address, let alone doing anything more positive like creating art or culture or community. It’s designed to exhaust us and to drain us and to waste our time. Toni Morrison talks about that with regards to racism and says one of the functions of racism is to put you in a position of constantly having to explain yourself and justify yourself, and to make you feel guilty if you do any other work besides that, but it’s really important that people do. It’s really important that trans and non binary keep making art, keep building communities. Because it’s important to tackle these issues head on, but it’s also important to do other things.

Think about the way issues around immigration have played out in Britain and the way that debate has functione, in the creation of the hostile environment and the sort of endless extension of it into something very, very close to fascism, if not outright fascism. What you saw throughout the 1990s and particularly into the 2000s, which I think were an incredibly pernicious and frankly nasty time in British politics and media, was people on the far right saying, ‘We need to have a debate about immigration, we’re not allowed to talk about immigration.’ Whilst pretty much every newspaper everyday would have screaming headlines, demonising migrants, demonising anyone who was supportive of migrants and advocating incredibly punitive policies.

You have been seeing for a while a similar process being applied to trans people. You’re seeing right-wingers, transphobes, gender critical feminists constantly saying, ‘Oh, why aren’t we allowed to, you know, discuss transition? Why aren’t we allowed to debate them? You know, why should we accept trans people?’ and demonising us, individually and collectively, creating an environment where we are basically not allowed to express ourselves within mainstream media and making it very difficult for us to find an audience. Then, when they feel they can get away with it, putting through a regressive policy. The endpoint of these discussions on immigration is basically the Rwanda policy, and the endpoint for these discussions on trans issues is what’s happened in Hungary, a complete revoking of gender recognition. Not just for people who are yet to get it, but people who’ve had it already. And again, don’t think they’re not going to try and do that, because that is the point where these people want to get to. This use of debate, it’s exploiting a loophole in Liberal ideology and finding their way in. So it does need to be resisted.

After conversations like this, it can be difficult to see the positive side for trans coverage in the media today – can we touch on that?

I do see new publications set up by younger people catering to a more explicitly politically-engaged audience of younger people saying, ‘We have these positions on social and economic issues that we think are right. And we’re not claiming to be objective on that.’ The fact that generationally, at least the more radical, or even just more social democratic politics and culture in this country, is a lot more explicitly trans inclusive than it was does give me some grounds for hope. Because I think younger people, we will win this argument eventually. Bear in mind, we have a Conservative party that’s basically pitching for the votes of over 60 years, and a Labour Party at the moment that sees its core vote as being between about 45 and 60 years, also pitching to people that age and older. But where the sort of tectonic shifts in society are going to be are amongst younger people, and younger people know more trans and non-binary people. They’re more likely to come out as trans and non-binary. They’ll read more about trans and non-binary people or watch more films and television programmes that we make or are in. They’ll listen to music that we make or are involved with, etc. I don’t like putting too much faith in the tides of history or the wave of the future, but you think about that famous line, don’t you? “First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win.” And you know very much in my youth and the sort of 90s, we were largely ignored. In the 2000s, we were very much laughed at. In the 2010s, we’ve had the battle of our lives. And I think that’s going to continue into the 2020s, but then we might win. We’re not going to win without struggle. But when is anything ever won without struggle?