Last Summer, I met a Palestinian artist on Fire Island and when we went our separate ways, she said, “See you later, cousin.” As an American Israeli, I couldn’t stop thinking about that.

It’s something my dad always says, that Palestinians are our cousins. But it’s hard to get that sort of sentiment from him during times like these when we turn to a very binary way of thinking: us (Israelis) vs. them (Palestinians). People like my dad don’t always understand that it doesn’t need to be one or the other, that being pro-Palestine (or even just voicing the desire for a people to not be completely wiped off their homelands) doesn’t equate being anti-Israel.

I truly will never be able to make sense of this moment, of what I’ve felt the past few weeks. I don’t expect to encapsulate all my thoughts perfectly, or touch on all the points necessary, but a friend once told me, “If you can put words to something, it’s probably not worth making.” While I try to be clear and adamantly state my views on something as simple as calling what’s happening in Gaza “genocide,” there are some things I will never be able to put into words, and that’s why art is part of how I process.

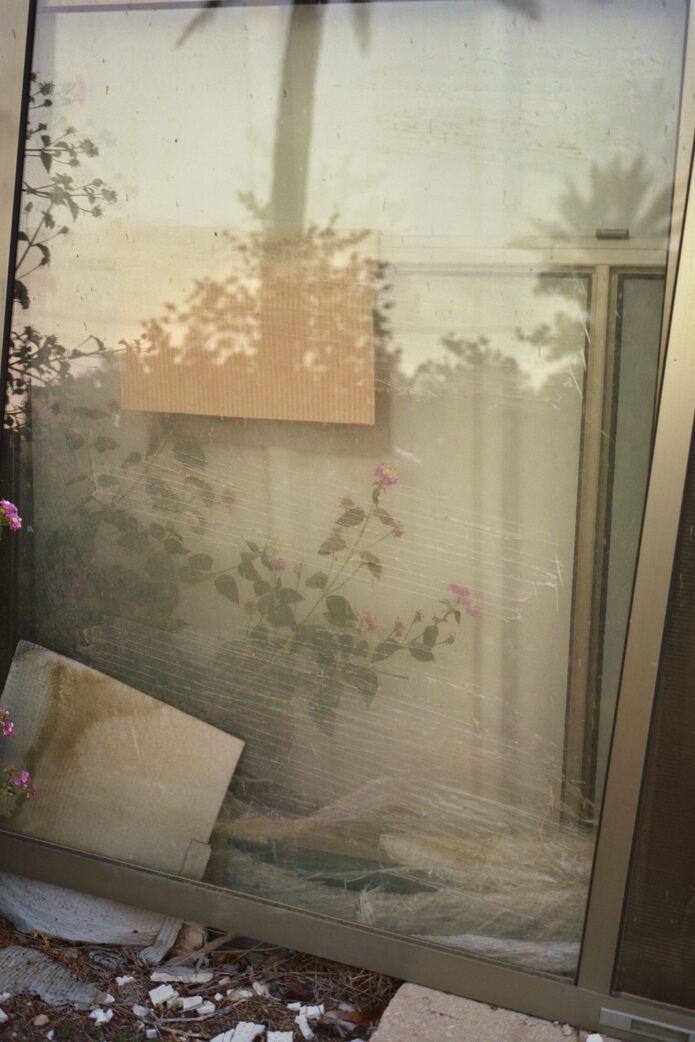

There’s a space between thinking and words and that’s where my photos exist. Where ideas I don’t necessarily know how to make sense of lie and where my endless questions live. Photographing a land that is so contested, that my history is so tied to, that I have a stake in, was the closest way to make it make sense.

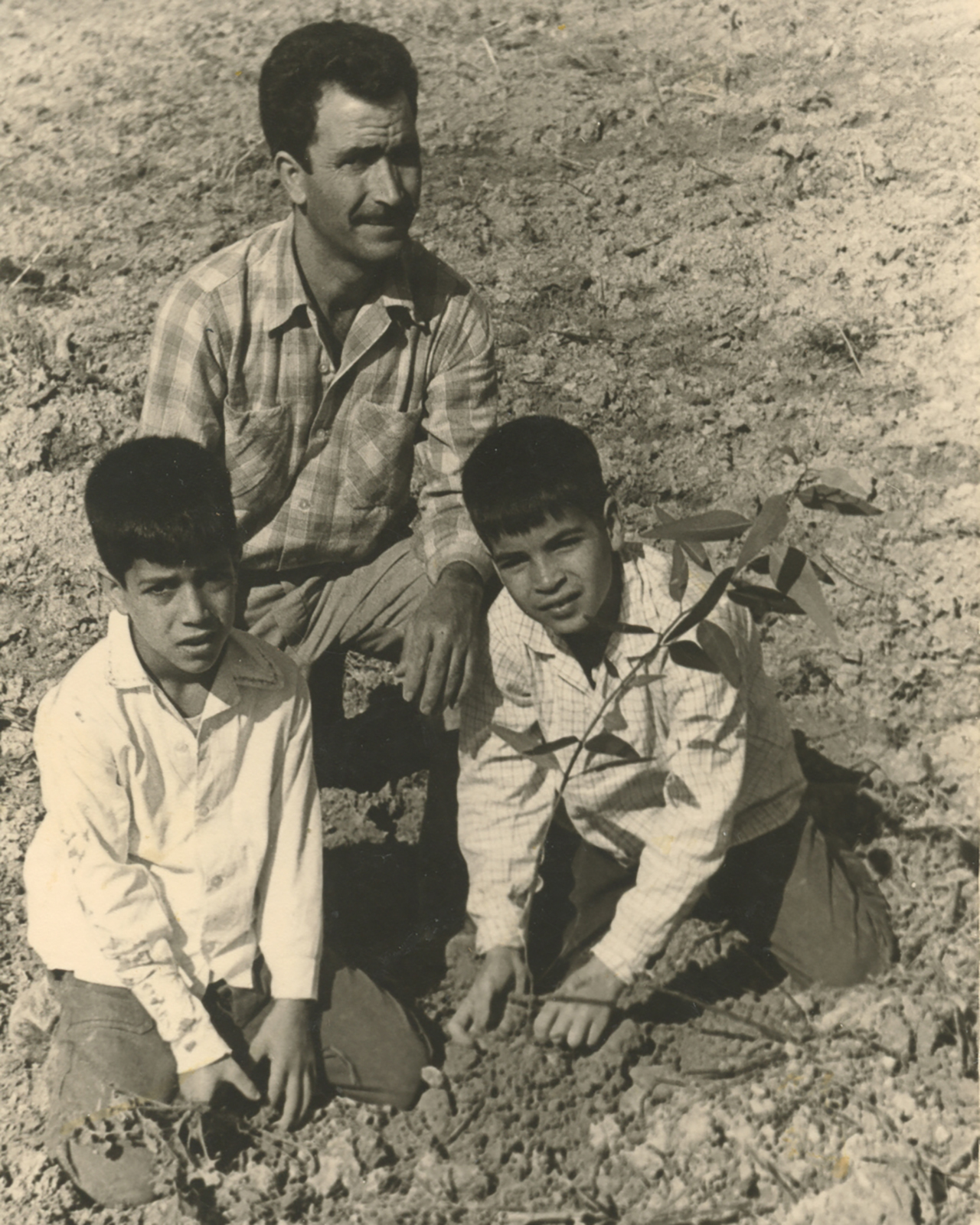

These pictures were taken 40 years apart in the same area. Above, my grandpa, dad, and his older brother were around the same age as my dad, older sister, and myself in the photo below. These pictures were taken in the Judean Hills, which used to be rich with olive trees planted by Palestinian farmers. When the state of Israel was settled, the Zionist organisation Jewish National Fund had an initiative planting trees on this land — land Palestinians sowed first.

In Palestine, the struggle for land can’t be extricated from the fight for agricultural right, which is ironically at the heart of the Kibbutz movement too. When I return to these images side by side, I see how deep the roots are. Zionist indoctrination starts young, passed through generations of planting and replanting.

I’ve been a dual citizen of Israel and the US my whole life. From ages 15-17, I had it in my mind that I was going to join the Israeli army when I turned 18. Thankfully, by the beginning of my senior year of high school, I had come to understand that my reality had been veiled through propaganda and fear. I went to art school instead (Truthfully, my mom would have never let me step foot in the army anyway).

After living in Israel for part of my childhood, we moved back to New York. When I did return seven years later, the sense of pride and nationalism I felt was overwhelming and intense. I can look back and see the power it had over me, how I equated my pride for Israel with an impulse to defend it. This is something I recognise in many people who live there. I hate to admit that at one time this is what I felt and thought, but I’m simultaneously grateful for the transformative unlearning I’ve done over the past 12 years through criticality, interrogation and experience. I’ve seen this same unlearning happen with many other Israelis and Jews.

What I’ve witnessed this month is an endless loop of trauma folded into itself. It’s unnerving to see people across the world completely blind to the ethnic cleansing happening in Gaza right now. The bloodlust happening in front of my eyes is the worst of our history repeating itself. While the Levant region is ultimately the homeland of both the Jews and Palestinians, Israel is a country that relied on violence in its founding. That violence is at the centre of its existence, in more ways than one, and I continue to be hopeful that enough people can imagine a different way of existing than the reality we are living right now. Hurt people hurt people. Oppressed people oppress people. That many fail to recognise, or don’t even attempt to recognise this, is only a weakness. To fail to see Palestinians as human beings is nothing short of a moral failing.

The violence inflicted on Palestinians is hurting Israel more than they can even wrap their heads around. Living in a place where violence is a daily reality isn’t a way to live. Our safety is bound together. Though some of my family sees this moment as a binary, I want to help them imagine another future. A different reality than the one my dad and uncles grew up in where they were the only Arab-Jewish family in their community.

Before 1948, Jews and Palestinians lived amongst one another without the intervention of the Israeli military. It’s possible to achieve. Nationalism leads some to think that if you don’t have all the power, all the land, all the protection, you can’t live at all, and that is such a failure of the imagination. We can build new worlds, we can oppose our own governments as a pathway to change, because our people, not our states, are the ones doing the living.

I once heard Angela Davis say at a talk, “I don’t think we can be consistently anti-racist, consistently anti-semitic without being consistently pro-Palestinian.”

“Most people who are opposed to racism include anti-semitism within that,” she said. “We are as passionately opposed to anti-semitism as we are to anti-Black racism. That opposition also includes a passionate opposition to the occupation of Palestine.”

Everyday I’m thinking about Palestinians digging with their bare hands to rescue survivors in rubble. Palestinians who’ve had no water in their homes, those who still have homes. Palestinians begging for rations of pita, Palestinians standing in piles of children’s bodies, Palestinians who haven’t showered in weeks, Palestinians who have lost their entire family, Palestinians who are now homeless, Palestinians who are now starving, Palestinians who have no anesthesia for surgery, Palestinians starting to hallucinate due to lack of water, food and sleep, Palestinian babies being born, Palestinians.

Our liberation is beholden to Palestinians, and theirs to ours. As a Jew, as an Israeli, as an American, as a queer person, I want to be part of an imagined future. I want a shared land, to live among our cousins again.