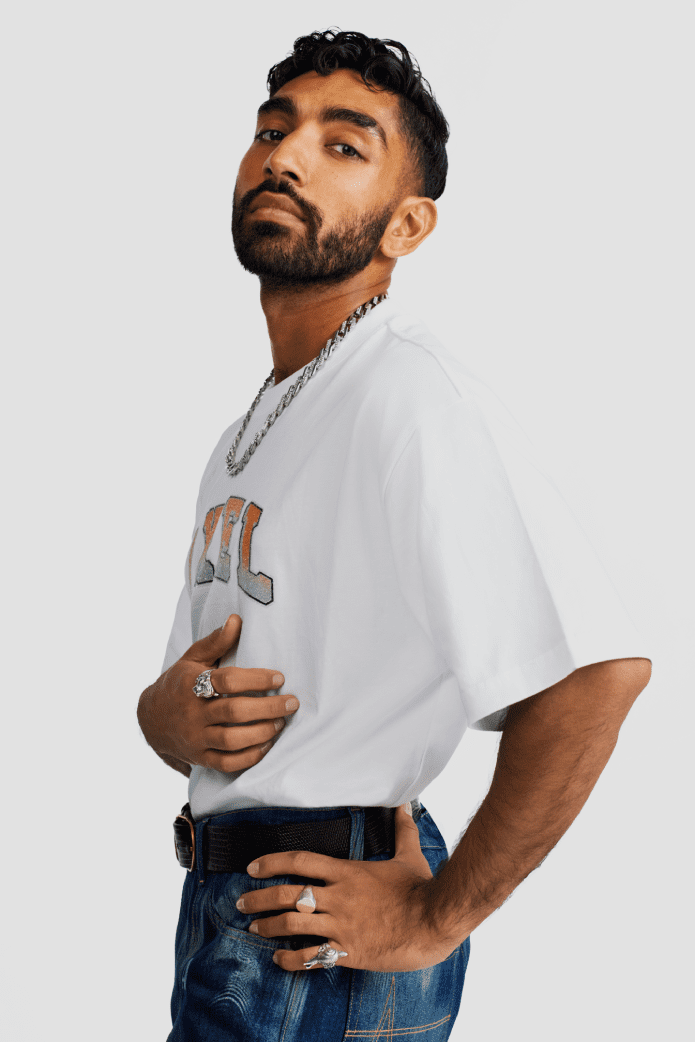

Mawaan Rizwan wants you to get acquainted with the unconventional. Yes, really. Known for his viral internet skits and on-stage antics, the London-based comic began his days as a self-made YouTuber. Here, online, you’re never too far from a bootleg zany parody or satirical spoof. Nowadays, however, Rizwan is known for his gigs on the telly and acrobatic reinvention of creativity. Whether he’s scripting a jingle about mangos or quipping about his amusing relationship with his South Asian parents, you can bet the London-based actor is imagining a wacky new idea.

Right now, Rizwan is settling down at Edinburgh Fringe Festival (it’s his tenth year at the staple event); a place where he comes to test the waters and absorb the genius splattered across stages. Each return, for Rizwan, is a recipe for inspired evolution — add a pinch of salt, silliness and unreadiness and you’re almost there. “Every year I come back, I try and break the mould I created last time. I try and push myself,” he says. The method, madness and motive all boils down to “reinvention”. You see, growing up, Rizwan wanted two things: applause and to be interesting. Whether he was shining under the glare of a stage light or the off-white hue of a laptop screen, the actor knew he wanted to be seen. Nothing, not even the prodding, off-putting comments online was enough to deter him. So, without industry contacts or a flowery degree behind him, Rizwan stepped up – trackies and all – and garnered his own sense of self. “I’ll be really honest, I started it all for a very vain reason, I wanted external validation. I wanted to be clapped and that’s why I became a performer,” he explains.

The glimmer of indefinite applause – and validation – trailed behind the comedian like a shadow in a circus. Soon enough, the crossover of presenting comedy and being public-facing placed Rizwan in a “very unhappy place”. He recalls his ascension online as negativity and prejudice came his way. The answer – or logical “foundation” as he puts it – went back to his DIY roots and, coincidentally, a Parisian clown course. “My clown teacher, Philippe Gaulier, very helpfully said to me, ‘Don’t go out into an audience looking for the validation of your parents. Validation from your parents is not gonna be in the audience. It’s got to come for you, otherwise, every bad gig you’ll have an emotional breakdown’,” he says. Now, the star’s success no longer feels like walking a tightrope but an opportunity to pull off playful sketches and spoofs with a healthy mentality. “If all this goes to waste, I can still go back into a room and I can make a sound on my keyboard and make a song. I could go and perform it to twenty people and I get a buzz out of that,” he smiles.

He’s faced walkouts, had Subway sandwiches chucked at him, and there’s still no stopping Mawaan Rizwan. Breaking into the comedy circuit is enough to put plenty of people off, but not this guy. With over 100,000 followers, the comic’s crafty tone has routinely assured him a cult following. It’s not a Rizwan show without a funky dance break, flashy clothing, or a skit that will have you chuckling in disbelief. When he’s not making fruity tunes about mango chutney, you can find his credits dotted around the TV scene. He’s appeared on Taskmaster, The Great Celebrity Bake Off, landed writing credits for Netflix’s Sex Education and, now, is spearheading his own fantastical-meets-physical BBC comedy series, Juice. Uniting his clown education and off-the-cuff internet demeanour, Rizwan’s new project is gloriously surreal and over the top. Juice is cunning, emotionally cutting, and an effortless crowd-pleaser. The trippy comedy follows a South Asian gay Londoner as he stumbles through the overwhelming every day. The catch, however, is that not everything is as it seems. Here, the comedy closet doesn’t just feel like it’s closing in on you, it actually is. In Rizwan’s emotional in-sync comedy cosmos, physical comedy comes to life, literally.

Watching Juice you’ll be curiously led, episode to episode, hooked on sharp screenwriting and tongue–in–cheek humour. So, how can a show couched in splashy, thrilling relationships maintain its endearing heart? “My mum always used to say, ‘Be bad, but don’t be boring!’,” Rizwan exclaims with a grin. “It’s insulting to an audience – they pay their ticket money and you’re gonna come on and do something mediocre? Put on a show! Give it your all because a lot of people live through you. They go to see a performance so that they can live vicariously and watch someone who is free, whether that’s physically, comedically or emotionally.”

Juice, in all its glorious pulp, is exactly this. When life gives you mangos, why not make mango lassi? The seed of Rizwan’s therapeutic series was planted in 2018, as he exercised an hour-long early rendition of Juice. Soon after, the actor began pitching to broadcasters. Almost a year later, during the pandemic, Rizwan got what he has long been waiting for — the green light. “[Juice] is a little capsule of everything I’ve ever wanted to do all in one place with all the people I wanted to work with. It’s a dream,” he says earnestly. And, of course, the eventful series pulls on his familial relationship – particularly his parents – who often make the punchline of his on-stage comedy gags.

Here, however, identity isn’t peeled apart and micro-analysed. Instead, he admits that his on-screen character shares similarities with him just because he can. It’s true, there’s no grand reveal made about queerness or being a young British Pakistani man in London. Instead, the production becomes a family affair with Rizwan’s brother (Nabhaan Rizwan) and mum (Shahnaz Rizwan) co-star lighting up smaller scenes. Juice becomes more than a funny title but a hearty series with a dysfunctional Pakistani dynamic as Urdu cuts across quick-fire dialogue, Rizwan makes out (and then some) in the toilets, and intimacy gets, well, weird and intimate. It’s a side of comedy and representation that’s not often given a chance. Rizwan, nodding, acknowledges the familiar sentiment.

“We have this story that we tell ourselves, that we’re not creative people, we don’t do artistic careers, or we have to be this or that and be conventional,” he gestures. And as an East London boy, he admits, the stakes were high. “There wasn’t room to fail. We had to be success stories because, otherwise, what was all the sacrifice for? That’s what parents tell us. At the same time, I feel like we’re inherently creative people in the South Asian diasporic community. We grow up around so much music, dance and artistic prowess. It’s all there, it’s in our blood. I can only really speak for myself, but I grew up in a very creative family.” Rizwan attributes his instinct for creativity to his mum who ran community events, functions and plays at his school. “My mum, whether she knew it or not, was a really big influence. She was subversive and didn’t fit into any box, she had this immigrant work ethic and was working hard, doing three jobs, raising kids and really wanted us to get an education, but in the same breath was doing the painting competition for the local community.”

This immersive free upbringing, Rizwan reflects, gave him the creative intuition to push on with a career in the arts. “[My mum] was very strict and she wanted us to really study and get our grades, but at the same time, I was like, ‘Hey, mum, I want to make a YouTube video. Will you wear this wig and do this rap battle with me?’ And she was like, ‘Yeah, sure!’” he laughs. “She was this charismatic, funny person. Growing up around someone who contains so many multitudes was really profound, whether I knew it or not and has informed how I make my work now.”

At 24, Rizwan made a life-changing decision: he came out to his Pakistani parents. Then, fresh off the out-the-closet boat, the actor fronted a BBC Three documentary, How Gay Is Pakistan? A well-intentioned exploration, Rizwan took an investigative eye to the country he was born in, notably Pakistan’s LGBTQ+ laws and lifestyle. “I look back at that and I don’t feel like that really represents what I’m about artistically. I feel like it’s a brash thing to make. Sometimes, I think for the creative process to prosper, you need to get things like that out of the way. It’s very identity-led and that does some good in terms of visibility,” he explains.

This immersive free upbringing, Rizwan reflects, gave him the creative intuition to push on with a career in the arts. “[My mum] was very strict and she wanted us to really study and get our grades, but at the same time, I was like, ‘Hey, mum, I want to make a YouTube video. Will you wear this wig and do this rap battle with me?’ And she was like, ‘Yeah, sure!’” he laughs. “She was this charismatic, funny person. Growing up around someone who contains so many multitudes was really profound, whether I knew it or not and has informed how I make my work now.”

At 24, Rizwan made a life-changing decision: he came out to his Pakistani parents. Then, fresh off the out-the-closet boat, the actor fronted a BBC Three documentary, How Gay Is Pakistan? A well-intentioned exploration, Rizwan took an investigative eye to the country he was born in, notably Pakistan’s LGBTQ+ laws and lifestyle. “I look back at that and I don’t feel like that really represents what I’m about artistically. I feel like it’s a brash thing to make. Sometimes, I think for the creative process to prosper, you need to get things like that out of the way. It’s very identity-led and that does some good in terms of visibility,” he explains.

Now, several years later, Rizwan’s affinity with the documentary has shifted. “I know it helped a lot of people and it would’ve helped me growing up because I would’ve seen someone making a thing about a certain intersection of identities that we’re told are not allowed to co-exist,” he explains. “You’re like, ‘Woah, there’s hope! I can live like that?’”

As the documentary served a creative purpose, he hoped presenting the project would give younger South Asian queer people a chance to see a version of themselves on-screen. “Looking back at it, my projects now are more nuanced and deal with certain complexities and don’t have titles like that. I think that feels like a more grown-up place to make work from.” Among the received controversy and hateful comments, Rizwan lightly admits he found a silver lining — “I also learnt that I don’t love being a documentary maker. It’s really exposing and it’s hard to make a documentary that’s nuanced and get across all the complexities of an issue like that.” Pausing, the comic mulls over where to lead next and gently adds, “But it changed my life doing that project. That’s all I can say about the project. It’s a tricky one.”

With YouTube virality on his roster, Apollo shows in his pocket and notable writing credits to his name, it’s not unsurprising that Rizwan seeks distance from the overexposure of a hard-hitting documentary. “Artistically, it’s not what I want to be making now and at the same time it was a coming-of-age thing that helped people; I appreciate both those sentiments. I think the reason I don’t wanna bang on about it is because I’m really glad it’s out there and it’s helped people and at the same time, it’s limiting,” he explains.

The personal repercussions of How Gay Is Pakistan? weren’t solely about the backlash but, rather, the creative repercussions, too. “Representation isn’t about getting a person from a marginalised community and pigeonholing them into making projects repeatedly about those identities. Once you make a project like that in the industry, you’re told, great, this is your thing now. You do stuff about being gay and you do stuff about being Pakistani, if you can do both at the same time, ding, ding, ding! Here’s your commission,” he says.

Moving away from the hyper-personalised documentary style gave Rizwan room to breathe and be reclassified in his creativity. “It’s so limiting as an artist because I wouldn’t be afforded all the same freedoms that the average artist gets,” he says. “With Juice, it happens to be a queer relationship and someone from a Pakistani background. We speak Urdu in it, in a matter-of-fact way, not because we’re trying to make a story out of it or being like ‘Hey, we’re the brown people who tell this story only!’ We’re just existing and it’s about being afraid to commit to a relationship and getting to know your parents better.” So, while the inroads of Juice pull on similar home truths, the writer is boldly able to retroactively look at his identity – on his terms – without the bigger personal pressure. “I get to just make what I want to make. Representation is about giving more opportunities to more of us so that we get a fuller spectrum of stories.”

It’s the height of summer and, surprisingly, Rizwan is not wearing a tracksuit. Throughout the comic’s career, the easy-going clothing staple has become a recognisable token. Even in Juice, Rizwan’s character cuts about London in a bright red trackie. Whether he’s kitted out in high-end designer gear or your everyday sports brand type. For many working-class South Asians, the commonality of tracksuits was a given. Who had thought a simple streetwear staple could become a visual bridge between Britishness and our broader identities? For Rizwan, it’s a bit of both but, he admits, it’s largely the ease of the clothing. “It is a comfort thing! Growing up I was always in tracksuits. So it feels true to the younger me, but also I remember doing gigs and wearing tracksuits. My agent said to me, it looks like you’ve not really made an effort. I was like, ‘No this is my best tracksuit!’,” he laughs.

In classic Rizwan style, he’s never strived to be conventional and uses his signature look to challenge gender expectations. “I started customising them and I would bejazzle my tracksuits and make them out of special fabric and stuff. That’s how I ended up having shiny glittery tracksuits. It was because I wanted to dance in my shows. It was boring because every other comedian was wearing jeans and a T-shirt.”

With over 10 years in the comedy game and new projects unfolding, Rizwan’s grateful for the moments he gets to reflect. Progress and passion were something instilled in him from an early age. As the release of Juice nears, the writer can’t fathom how an audience will react, but he’s hopeful for a positive response. “There’s so many hoops to jump through in telly. Me and the directors, we love visually surreal stuff, it really makes us get excited and jump up and down on our sofa when we’re watching TV, especially if shows go to a place you don’t expect them to. I hope people latch onto that and get as much pleasure out of it as we did making it,” he says.

The end game, for Rizwan, has always been simple: deliver something outrageous and enjoyable. And, with Juice, he’s held up his end of the bargain. “I think it’s hard to make stuff that feels emotionally truthful and visually adventurous and surreal and that is what I get excited about in terms of the show. When you go to watch it, the sentiment should be ‘Strap in!’ and you’re like ‘Woooh!’,” he jokingly imitates over Zoom. “Surrender, like when you’re a kid and you’re on a rollercoaster, and trust it to take you [away].”

Juice is out on BBC Three and iPlayer this September.