I’m a black queer man. Come this December, I will have been a black queer man for 37 years – Sagittarius for anyone who’s asking. For those 37 years, I’ve always felt a faint void inside; an absence, like a steady hum, that has followed me throughout my life.

It was there in high school when I overheard my dad tell a friend how he read my journal and didn’t know what to do about his gay son. It was there when, as an adult, someone I thought I knew – a white gay cis man – called me the N-word. He actually said it to his then boyfriend as in: “How could you bring that N-word into my house?” And it was there last year when my oldest brother finally succumbed to his decade-long battle with HIV/AIDS. These are the times in my life I’ve felt the lowest and when the hum has been the loudest.

It wasn’t until recently that I realised the hum wasn’t that of a void. No – it was instead the pulse of a beacon. In those dark days, my consciousness craved a like-minded soul. Someone who understood what it’s like to grow up black and queer in America; a unicorn, hiding in a horse-costume, so as not to offend/frighten/provoke other actual horses. Since this realisation, I’ve actively sought out meaningful conversations with other black queer men that go beyond the latest Cardi B meme or weekend party line-up. In those conversations, I’ve discovered similarities that calm my heart, differences that challenge my soul and a freedomto-be that could only come from brotherhood.

Related: Chance Perdomo on bringing some much needed same-sex romance to the Sabrina reboot

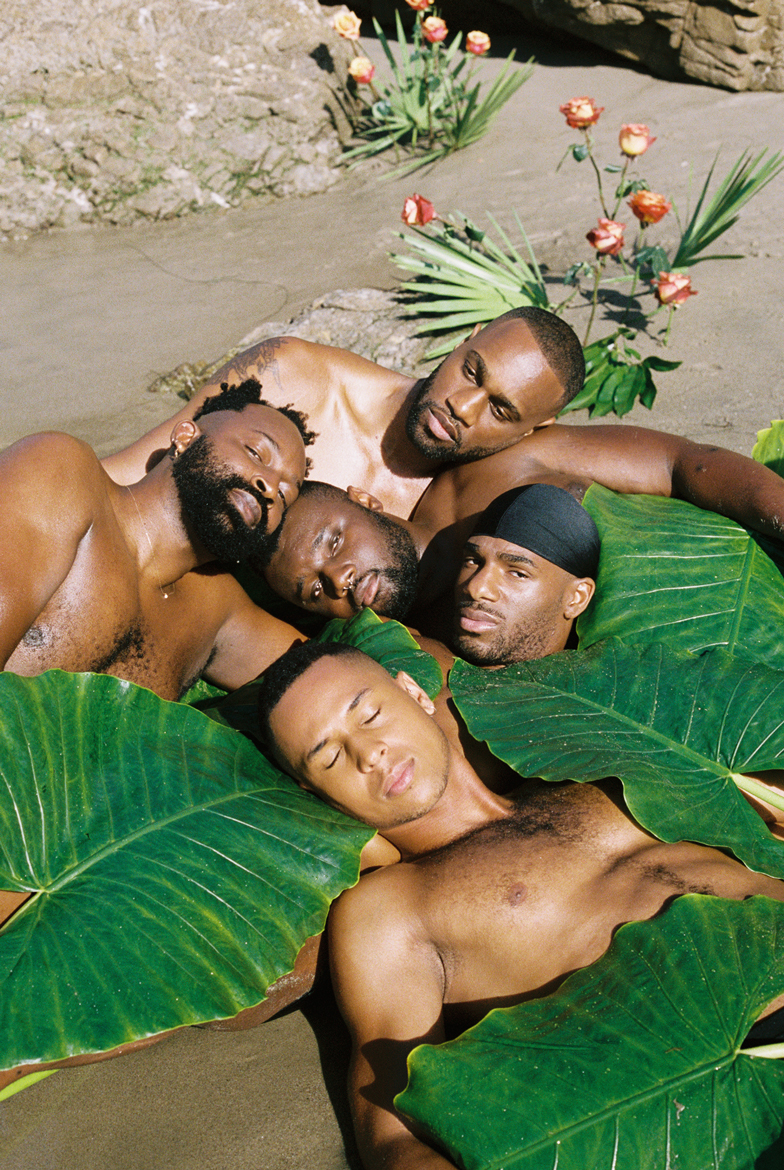

So when Gay Times asked me to take the creative reins for this feature during UK Black History Month, I immediately knew I wanted to replicate the feeling of discussion we POC queers seldom experience. I set out to cast a group of creatives of different shades, sizes and backgrounds to have an honest conversation about what it’s like being a young black queer man in 2018. I was lucky to find willing participants in James Bland, Emmy-nominated actor, director and creator of the YouTube series Giants; Rakeem Cunningham, artist, activist and photographer; Maurice Harris, artist and owner of Bloom & Plume Floral Collective; Devin Wesley, artist and former track and field athlete; and Tokeyo, a rising musician.

When is the earliest you can remember understanding your queerness or blackness as ‘other’, or not a societal norm?

James: I would say for me I think blackness came first. In school particularly, as an athlete and as an honor athlete, in terms of being the ‘smart black kid’, but queerness wasn’t far behind. I just remember I felt like masculinity initially was a learned trait because I was called a ‘faggot’ or I was called a ‘sissy’. I learned that there were certain things I couldn’t do if I wanted to fit in, but I think the thing that’s unfortunate when you’re growing up… there’s no place for queerness in blackness. And so, you tend to lean more towards blackness as a male.

Rakeem: I think that’s what’s important, too. At the end of the day, those things can exist in the same space. You can be queer and black and play basketball, but a lot of times we’re forced to kind of choose. It’s always ‘or’ as opposed to ‘and’.

Tokeyo: I remember I had a moment when I said ‘Ok, I am very, very queer’. One day, I saw this pink nail polish and was so freaked. Mind you, I’m five or six. I didn’t know what nail polish is, but I know what they do with it… so I did my nails. Looking at it in the mirror like ‘It’s poppin’, and then it’s dinner time and I’m with the hand soap and I’m scrubbing and this ain’t coming off. This day, it was fried chicken and french fries which is hand food so there was no way I could eat like this. I have two sisters, a little brother, a mom and a dad and I remember at that moment everybody. When I noticed I was queer, everybody else did too.

Related: Watch George Shelley explore the phenomenon that is ASMR for the very first time

You all use yourselves as subject matter in your art. In what way has being your own muse challenged your art and challenged thoughts about yourself?

Maurice: For me, I would say I’m a little more challenged by it just because I struggle being ok with myself with all the images that are poured at me constantly, and so I use myself. I forget who said this quote: ‘Be the change that you want to see in the world.’ If I want something to shift or be different or change or whatever it’s like, well bitch, start with yourself.

James: That’s a good quote: ‘Bitch, start with yourself’.

Tokeyo: I empower my body so much. If you see any of my videos, I’m either half naked or somewhat naked because 100% people can look at that – people that work nine to five jobs – they’ll see that and be like ‘Oh my God, that’s so much. That’s so extra. That’s so raw.’ But me, I believe every inch of my blackness, of my curves, of my abs, of my face, of my nose, of my lips all of this blackness is beautiful.

James, you’ve spoken about the idea of being paralysed by perfection in the creative process. As black men, we’re often taught we need to be ten times better than our white counterparts. How do you balance this idea of trying to give 110%, but also compromising and editing so you can get your work out there?

James: Yeah, I constantly remind myself I am enough in this very moment. I have to just remind myself that everything I’ve done up to this point has prepared me because I am a summation of all my experiences. So the way I do that is I allow myself to be honest. For example, on Giants Season 1, every [episode] was a first draft. I didn’t rewrite anything, and that allowed me not to get paralysed by perfection but to be as honest and as vulnerable and as raw and as unapologetic as I could possibly be. It was really sitting at the computer and writing what I felt and putting that on screen.

Maurice: It took my little brother to tell me this: ‘When you’re working IN your business, it’s like being on a hamster wheel and you’re going nowhere. You have to work ON your business.’ Ya know, you can’t manage everything, you literally can’t do it.

Related: Courtney Act is here to educate the nation on the truths of bisexuality

Rakeem: It’s hard because we’re trained though. I don’t think anyone at this tables’ parents told themYou know what, grow up to be mediocre. That’s going to be great. Everyone’s going to love you’.

Maurice: But I think that’s also the thing that’s been freeing for me, really acknowledging and understanding that hard work is not a black issue, it’s not a white issue, it’s an American thing.

Rakeem: Exactly.

Maurice: It’s liberating to know that we’ve been sold this story about hard work being this thing. Like if you work hard and get a degree and you do all that, this will pay out in this way… and I literally don’t believe that anymore.

Rakeem: No that’s bullshit.

Being part of a minority; queer, back, even a creator, you often hear about the ‘crab bucket’ mentality when it comes to success. People pulling each other down or not letting others succeed at the mercy of everyone else. Have you seen this in your work at all?

Devin: I think we experience that a lot in our community just because we all naturally feel that pressure to be the best. So, we want to make sure that no one else surpasses us and we stay on top, and we feel like everyone is competition.

Rakeem: Yeah and it’s also the atmosphere too ‘cause it’s set up like that for us to argue. It’s why slaves weren’t allowed to read. It’s why they weren’t allowed to write, because when we come together and support each other shit happens and shit gets

done. People are scared of that and that’s why a lot of times we’re put in situations where we’re forced to compete and forced to feel like we’re each other’s enemy when that’s not really the case.

James: Because this is not by our design or our making. This idea in terms of black folks being crabs in a barrel, no one ever [points out] that there’s boiling water at the bottom of that barrel. So, they’ve literally thrown us into this barrel where there’s

boiling water.

Maurice: OK.

James: So us clawing at each other… we’re trying to survive.

As creative people, you’ve all faced some kind of rejection. Does anyone have an example of a good ‘no’? A ‘no’ that was given to you that actually turned out to be something really great? Something that took you down a path you wouldn’t have seen?

Devin: I think the biggest ‘no’ I’ve ever received was a metaphorical ‘no’ from the Universe. I was a very competitive track and field athlete for the majority of my life and after college I was trying hard at going professional – I just could not get it together. I just couldn’t stay healthy. I kept getting injured and just lost so much of my identity that I had created for myself being this ‘You were the top athlete. You were the gay black athlete’ which, in my awful mind, made me feel accepted. It was ok for me to be gay because I was an athlete. If I lost that, then who am I? So that forced me to come to terms with things I do like and the person that I want to be and how I dress. And the labels that people like to put on me: ‘light-skinned’, ‘top’. I just say ‘Fuck that. I do not want to be labeled’.

James: I see how you slid that ‘top’ in there.

Related: George Shelley opens up about keeping his sexuality a secret while in Union J

Rakeem: I’ve always found that really interesting because it comes off to me as not a complaint on the labels themselves, but more a complaint on what the labels mean. And I feel like sometimes, for black people, because you say a ‘black artist’ it assumes that everything is going to be this certain kind of way. And I think the issue is allowing black people in the room to do whatever they want to do versus saying ‘being a black athlete means this. Or being a black painter means this. Or being a black model means this. Or, being a black photographer means this.’ It should mean whatever that means for just being a photographer.

Devin: Right.

But don’t you think that as creators, you paint, you write, you create what you know? I think white Americans aren’t constantly bogged down by their whiteness. Where as black Americans, every day I’m thinking about being black. So, when you create art, you’re pushing that energy out…

Rakeem: Oh, yeah!

So there’s freedom once you can finally transcend that and say, ‘Oh, I’m just going to paint flowers all day’.

Rakeem: I don’t want to transcend it. I’m black. I’m a black artist. That’s what I am. Period. Peeer-i-od. So if that’s what’s going to happen, I don’t care about being labeled a black artist. What I care about is what that means.

Devin: And how that’s defined. Your black art is different than my black art.

Rakeem: Exactly

Buy the latest issue of Gay Times

Photography Clifford Prince King

Words and Art Direction Matthew Pipes