Coaches barking instructions, darting footballers crying for the ball, and scattered applause from onlookers provide the soundtrack to our evening spent at Hackney’s Mabley Green. Here, under the unforgiving glare of floodlights, Arsenal staff are gathered for a special training session. Not too long after, we’re joined by a host of Wonderkid FC footballers – a local grassroots LGBTQ+ inclusive football club of women and non-binary players – decked out in their signature all-black kit, who begin their training by nimbly threading balls through cones.

As a young girl camped around a TV blaring Match Of The Day with my dad and brothers in the early-mid 2000s, women and non-binary players tearing up the televised pitch in place of men sat well beyond my imagination. Little did I know that women’s football in the UK had long existed and, crucially, had long been popular, with the oft-cited example of a sell-out Boxing Day women’s match in 1920 – a crowd of 53,000 watched on from inside Liverpool’s Goodison Park.

A year later, on 5 December 1921, the English FA formally banned women’s football which was, at this time, primarily played by women working in WWI munitions factories. Their reasoning? So-called medical experts asserted that football could damage women’s ability to reproduce. The sport was ‘quite unsuitable for females’ and the ban wouldn’t be overturned until 1971.

Fast forward to the 2020s and women’s football is now described as the fastest-growing sport in the UK. A flurry of broadcast deals with Sky Sports and BBC, record-breaking match attendances, and a trophy-clinching Euro 2022 for England’s Lionesses have underscored the sport’s revival, alongside independently organised pub jaunts for fans of women’s football, grassroots tournaments, screenings, parties and the like. The Arnold Clark Cup and Conti Cup have become staple sporting events, the fixtures appearing in and around the top-flight Women’s Super League schedule. According to the FA, the period between September to December 2022 saw a 12.5% rise nationally in registered female players, while June to December saw a 5% increase in female-affiliated clubs.

The explosive interest in women’s football, however, builds upon a wealth of local grassroots teams like London’s Hackney Laces, Bristol’s Banana FC and Manchester’s Rain On Me FC, some of which had been set up prior to the Lionesses’ impressive 2019 World Cup campaign, other amateur teams capitalised on the wave of popularity to set up or hugely expand their teams. And, for clubs like Wonderkid FC, inclusivity is baked into their teams and overarching ethos. As the players continue warming up on the East Hackney pitch, every now and then, you can spot the words “BE YOURSELF” emblazoned on the back of their training shirts.

Established in 2016, Wonderkid FC’s beginnings stem from a mistake. That year saw the release of an anticipated short film by Rhys Chapman. The film, Wonderkid, follows a gay professional footballer trying to find his footing in an environment where hypermasculinity and homophobia reign supreme, from the training ground to the pitch. Following the film’s acclaimed release, the Wonderkid project received a tweet which mistook them for an actual football team and invited them to play in a tournament. “We took that opportunity to start a football team because I had a load of mates who wanted to get back into football,” Maria Sihaloho, one of the club’s founders, explains. A call-out was swiftly made, a tournament team assembled, and the rest was history. “We had such a great time and it’s kind of continued since then.” It’s a space they describe as for “whoever doesn’t feel safe within football” and thanks to the reliable medium of word-of-mouth, the club has only continued to grow and bring more people into the fold, boasting a varied age range and players with all manner of day jobs and professions.

The kind of community-centred football Wonderkid FC plays and advocates for has caught the attention of many, including top-flight team Arsenal whose Emirates Stadium sits five stops away from Mabley Green. And it’s why, for this East London evening session, they’re joined by a player for the Arsenal Women’s team. Jen Beattie, a defender with 143 Scottish caps under her belt, cuts a striking figure and it’s little wonder that one of the Wonderkid players nervously titters when later marked by Beattie during a training exercise.

It’s a ‘one club’ mentality, no matter what background you’re from

For the queer professional player, engaging with a team like Wonderkid FC just made sense. “It’s a local London club which is something that Arsenal really values and we love what they’re doing,” Beattie explains. Talk of the Wonderkid film, and the way it confronted abuse and homophobia in football, had made its way to Arsenal HQ and, in the defender’s opinion, “it was a no-brainer for us to get involved.”

💬 "It's so important to remember what people have done to get us here."

For LGBTQ+ History Month, @jbeattie91 teamed up with Wonderkid FC to share what it means to find an inclusive community through football 🏳️🌈

— Arsenal Women (@ArsenalWFC) February 27, 2023

She goes on to explain the different ways that Arsenal staff and professional footballers have been supported by the club, including the establishment of Gay Gooners, Arsenal’s official supporters’ group for LGBTQ+ fans back in 2013. This February marks 10 years of Gay Gooners’ meet-ups before home fixtures, group trips to away games, regular social events, an annual presence at London Pride and directly liaising with the club on anti-LGBTQ+ football discrimination in football. Additionally, it’s in fact Arsenal’s LGBTQ+ staff network that organised the meeting between themselves and Wonderkid. “[The LGBTQ+ community insights] are coming from experience and I think that something that Arsenal really value,” adds Beattie. “It’s a ‘one club’ mentality, no matter what background you’re from.”

The campaigning and community-centred work being done by clubs at every level is heartening but it takes place against a backdrop of stasis when it comes to globally supporting and celebrating queer footballers and fans. Ahead of the 2022 Qatar World Cup, the captains of seven European teams – England, Wales, Belgium, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Germany and Denmark – had planned to sport ‘OneLove’ armbands, featuring a rainbow flag, in protest against Qatar’s anti-LGBTQ+ legislature: for example, under Qatari law, ‘sexual acts between people of the same sex’ are illegal and can incur the death penalty for Muslim men in Sharia courts, and a person in a ‘same-sex couple’ is considered to be unfit to be a guardian.

Following FIFA’s threats to impose sanctions, like getting booked or forced off the pitch, on players wearing the armbands, the seven nations confirmed they would not wear the armband. Feelings of betrayal cut across queer groups and organisations, both within and beyond the footballing world. LGBTQ+ fan network Pride in Football voiced the frustration of many on Twitter: “Countries, teams and players are happy to defend LGBTQ+ people until they themselves are at risk. LGBTQ+ Qataris face a bigger punishment than just a yellow card. The gestures and the activism ended quite easily at the thought of reprimand.”

I wanted to represent and, you know, make it a safe place for everyone

When we ask her how the LGBTQ+ campaigning sits alongside what happened in Qatar, Beattie answers with a rueful smile. “So much progress has been made but there’s still so much work to do.” Chatting to GAY TIMES pitchside, the Gunner smiles as she reflects on her own international appearances: “I’ve not captained Scotland many times, but the one opportunity I did have, I was straight over to the rainbow armband. I wanted to represent and, you know, make it a safe place for everyone.”

Beattie’s response is unsurprising, especially considering the sheer breadth of visibly LGBTQ+ footballers in the Women’s Super League, let alone other divisions. The likes of Arsenal and Brighton & Hove Albion have seen couples in their squads, while inter-team romances abound. A queer presence in football has long been evident and, despite the possible scope for discrimination, abuse and malignment whether as a player, staff member or fan, the beautiful game still calls us.

But rather than depending on clubs and international bodies to build more hospitable spaces, players have flocked to grassroots teams that reflect their values, needs and communities; where certain gestures may falter and crumble under the first sign of pressure, local players depend on themselves and one another to carve the spaces they want to be a part of. Hackney Womens Football Club – established in 1986 and often referred to as the ‘first gay women’s football club’ – joins Wonderkid FC, Stonewall FC, Romance FC, Babe City FC, Baesianz FC and excellently-named Ex-Girlfriend FC as just a few of these necessary emergent spaces. Meanwhile, football commentary and analysis from a queer lens (with a healthy dose of memes) are provided by collectives like Studs, This Fan Girl and Huns FC. To say that it’s an exciting time to be a queer babe who loves football is a woeful understatement.

The Wonderkid players and Beattie end their training session sitting in a circle on the well-trodden grass of the Green. Together, they discuss their hopes for the future of football and the joys and challenges faced by grassroots players today, including a lack of pitch availability and ensuring training sessions take place in hours when players can safely get to and from the pitch. The obstacles are widespread and, speaking to the BBC, Helen Hardy, from Manchester Laces, also notes that harassment and abuse from onlookers stubbornly remain: “All the experiences of abuse I’ve had have been post-Euros. We’ve trained on the same pitch for two years, but now there are comments from men walking behind the pitch – ‘go on darlin’ put it in the top corner, show us what you’re made of.’”

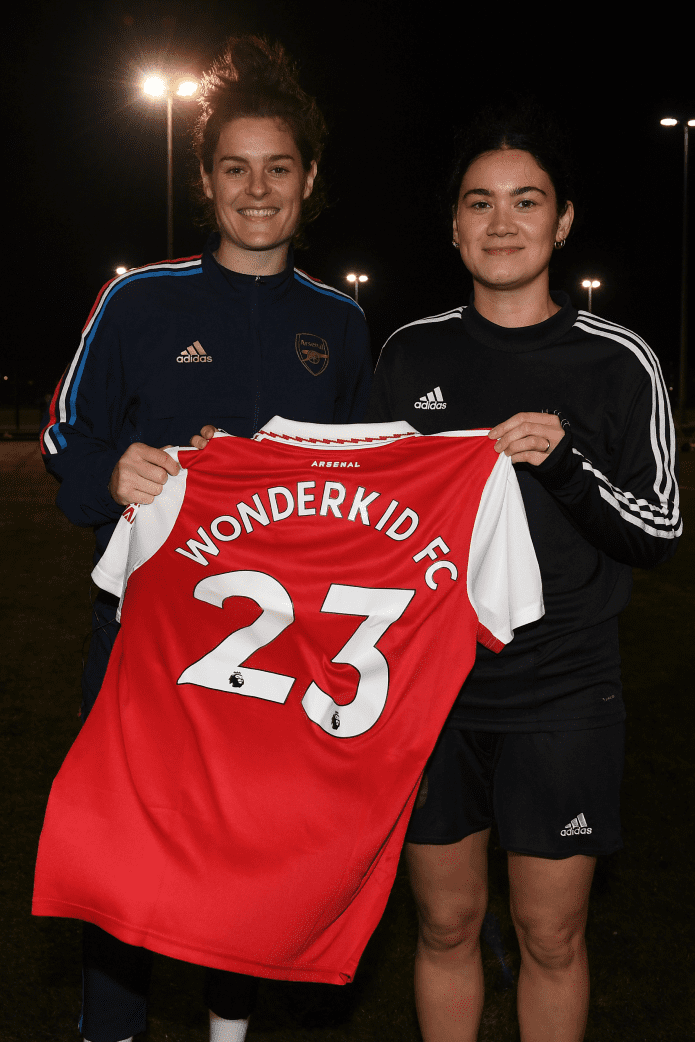

Unfortunately, queer women and non-binary footballers aren’t strangers to occupying the margins of the public’s imagination. And after the Wonderkid team is presented with Arsenal pride t-shirts and a personalised Arsenal replica shirt for the team (one player remarks on how the merch will incur the wrath of their Spurs-supporting family member), together we traipse to Homerton’s The Adam and Eve pub. A regular haunt for the local team, you can’t escape the irony: 20-odd queer folks sitting under the beer garden lights of a pub named after a biblical couple routinely invoked against LGBTQ+ communities. But this is what we do from the margins; we bend, break, occupy and rebuild spaces until they’re fit to hold us, whether it’s a spot for pints and burgers or the entire footballing landscape.

Watch Arsenal’s Jen Beattie team up with grassroots team Wonderkid FC below.